The trees at Malabar Farm are valuable. To loggers, they are a trove of highly saleable timber.

To folks who walk the forest trails, however, to those who escape to Malabar for peace of mind and communion with the Earth, these woods don’t have value: they are priceless.

The deep woods have a timeless aura about them, and hiking through that serene world it is hard to imagine such a peaceful place could be the source of any high anxiety or apprehension—yet in 1957 there were people racing all around the country in great distress trying to keep this stand of trees intact. Those people had a keen sense of how valuable these trees are and what it would cost to preserve them.

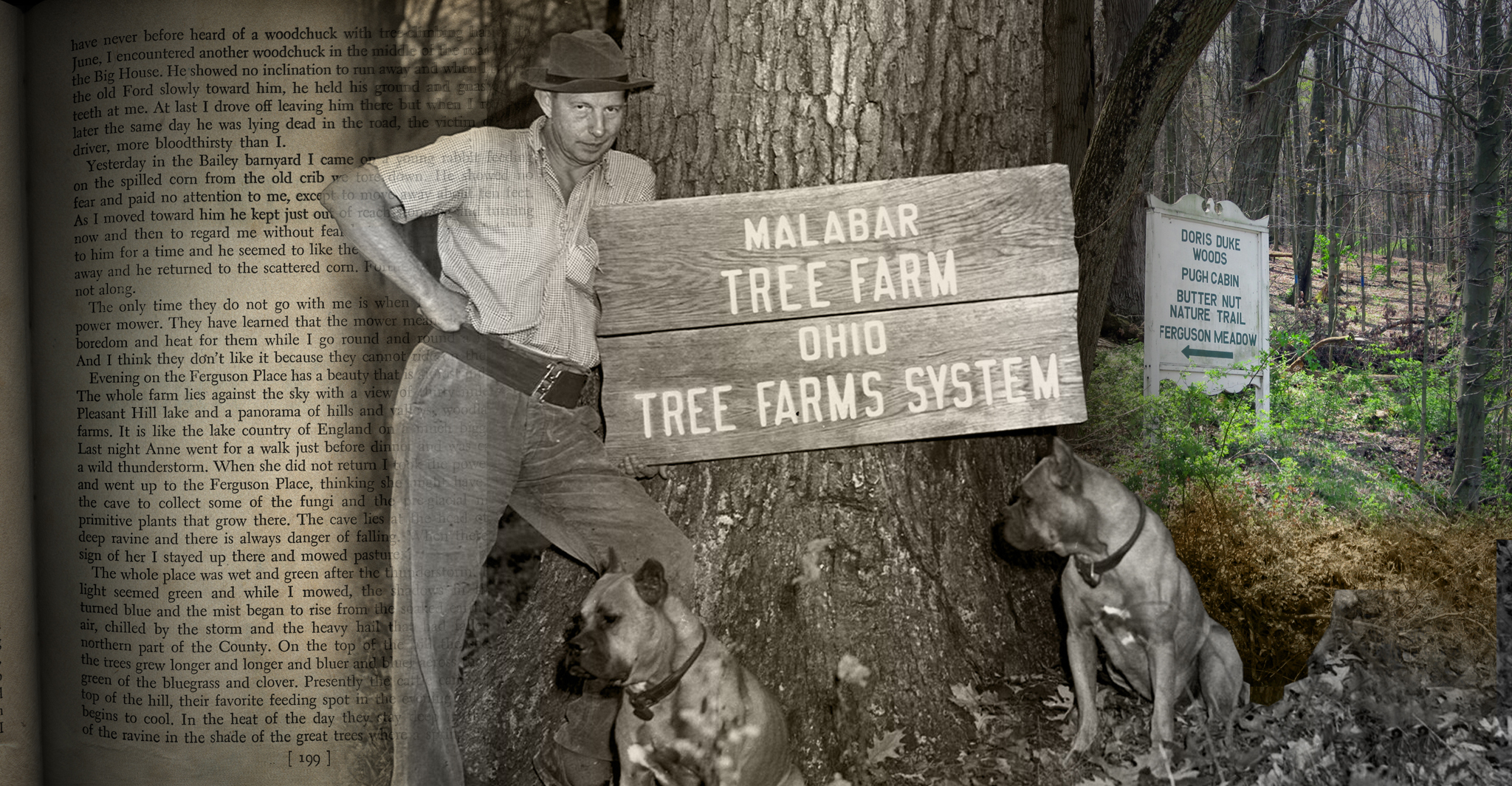

Louis Bromfield, the man who named the place and made it a landmark in American history, knew how precious walking in the woods could be—he wrote books about it. He spoke about it on the radio every week, and in conference rooms and auditoriums 150 times a year all over the country. He published weekly newspaper columns in cities and towns all across the nation in order to keep Americans vigilant about how important it was to protect the forests.

The word he used was Conservation.

Conserving means saving; making sure something precious survives another season, another year, another lifetime.

Louis Bromfield was tireless in his efforts to inform people about what it takes to protect the Earth. He was undoubtedly the nation’s, and the world’s, most recognized conservationist in the middle of the 20th century.

What made Louis Bromfield a great conservationist and historic force in American agriculture was not necessarily his ideas: those ideas he borrowed from age-old lore, and from the practices of farmers and scientists around the world who dedicated their lives to farming.

What made Bromfield absolutely invaluable to the agricultural world of his time was the fact that he was famous. Louis Bromfield was a household name and when he spoke, people heard him. Millions of people heard him.

Great scientists and water experts and soil authorities could talk all day and write innumerable intelligent articles, yet those words were all but lost in the sea of 1940s media.

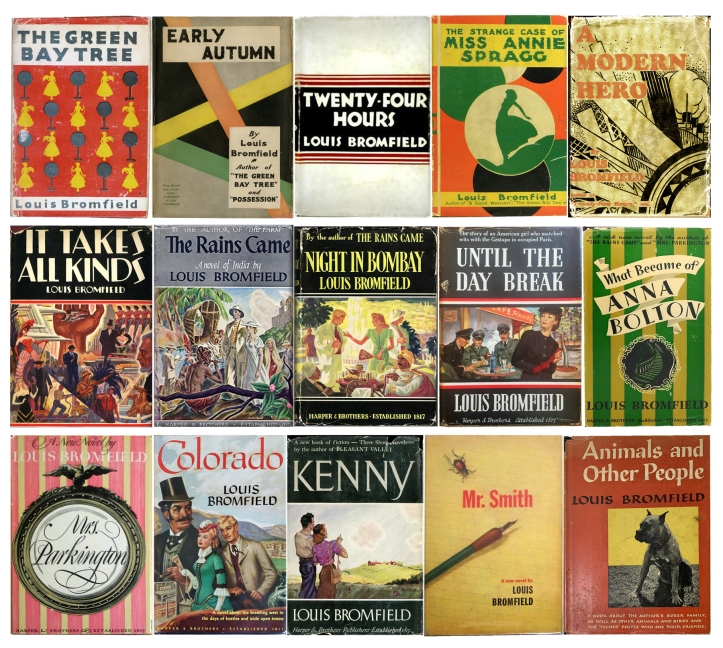

When Bromfield wrote words, people read them. The public had been reading him for two decades and made his novels best sellers. They had been watching his movies from the time motion pictures could talk, and they saw his name on the screen in huge letters with the biggest stars of their day.

The reading public, the movie-going public, the news and celebrity-gossip-hungry public were all very familiar with Bromfield by the 1940s, and they loved him.

So when he started writing about a crisis in American soil, and how it impacted the food every person ate—people paid attention.

His name came to be associated with saving the nation, and he came to be valued for his informed relationship with the natural world.

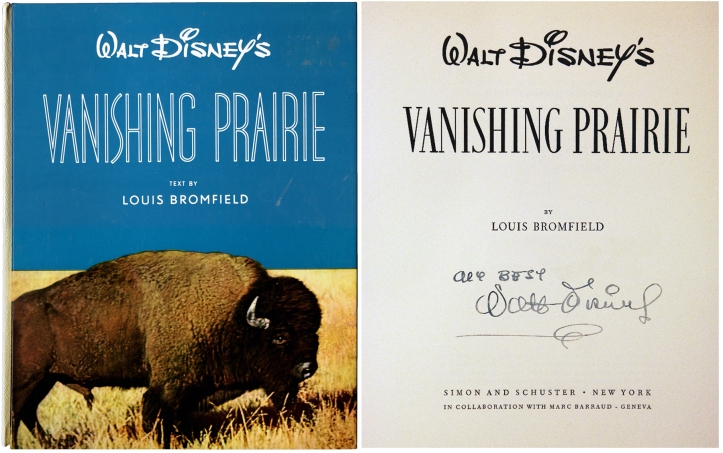

When Walt Disney started producing a series of movies about nature and animals—the True Life Adventure series—he naturally wanted Louis Bromfield to be a part of it because the Bromfield name immediately brought credibility and integrity and popularity to the project.

The ideas Bromfield spoke about saving the planet from careless erosion were not his ideas, and they weren’t new ideas; but because he was the one talking about them, conservation took on a brilliant popular immediacy.

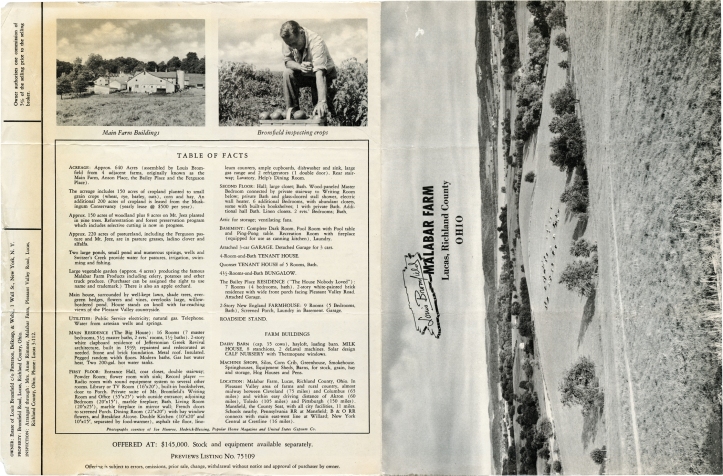

Bromfield built Malabar Farm from the ground up in astonishingly short time—he lived there only 16 years before he died, yet it had already, by that time, taken on the patina of an age-old institution, as if it had always been there guiding the ideas of American farmers.

The nation’s understanding of cultivation and agriscience changed dramatically during that difficult era of history largely because of Bromfield’s efforts: the practices of farmers evolved to support a healthier and more sustainable farm industry because of his voice.

There were many people in the upper branches of government who recognized what a priceless treasure Bromfield had been to the history of US Agriculture; and what a landmark in US history Malabar Farm represented.

So when he died suddenly there were a great many people holding their breath to pray the farm would survive his lifetime.

A lot of people worked very hard to make it so, and made determined sacrifices to drive the cause up to the very highest desks in the land.

Taking the lead in the race to save Malabar was an organization called the Friends of the Land—a national association of conservation-minded farmers and farm agents, scientists, scholars and Senators. Bromfield had helped found the group in 1940, and he had served on its governing board.

The Friends of the Land contacted all of Louis’ friends to rally support for protecting Malabar. And what an astonishing lineup of friends they were: a veritable Who’s Who of 20th century American entertainment, literature, politics and industry.

Walt Disney spoke up for his friend Bromfield, and actors James Cagney and Lauren Bacall donated a thousand dollars each to save the farm. The Secretaries of Agriculture from three different Presidents all spoke up. Authors and publishers, national celebrities and foreign princes added thousands more dollars to make their voices heard.

Even schoolkids from Ohio, Indiana, Illinois and Iowa collected pennies to buy back Malabar from the loggers.

There was great urgency because it was not a sure thing that Malabar would survive. Developers with cash in hand were ready to turn “America’s Most Famous Farm” into a dude ranch and golf course!

The old-growth forest was already marked for timbering, with paint blazes on the bark of ancient trees.

The Friends of the Land, and the friends of Louis Bromfield had to outbid the asking price of $145,000. In today’s money, that would be 1.3 million dollars.

Donations poured in, but as the deadline drew near in May of 1957 the account was still short.

That was when Doris Duke called.

She wanted to know what she could do to help. She could do plenty, because at that time she was often written of as the ‘richest woman in the world,’ and she was unquestionably America’s best-known philanthropist. She also loved trees and forests and the natural world, and she rose to the defense of Mother Earth again and again in her public works.

And she also happened to love Louis Bromfield. They were long-time soul mates who nurtured and supported each other in their work to protect the planet. Had he lived a longer life, the two of them may well have become wedded mates as well.

Most people around here who have heard the name of Doris Duke know it from a sign on the edge of the woods at Malabar Farm State Park. The farm put the sign up originally in 1957 to honor her after she gave a check for $30,000 that sealed the deal and put Bromfield’s deed into the hands of the Friends of the Land.

It was an investment she made in the future: the future of Malabar Farm, of course, and also the future of an America where scenic forests can be valued and appreciated and protected. It was an investment we repay every time we enjoy walking in the woods at Malabar.

All the hard work of the Friends of the Land and Doris Duke will be repaid a thousand times when our grandchildren walk in those woods and breathe the forested air of Malabar.

As a former Mansfield resident and frequent visits to Malabar Farm, this bit of Richland County history was of particular interest. In 1954 I attended a corn roast, along with several other college bound Mansfield Senior High students, that was hosted by Louis Bromfield. Listening to some of his college days and subsequent life experiences are treasured memories.

Thank you so much for your periodical articles on Richland County history.

Aloha,

Paul Haring

LikeLike

Dear Tim, Thank you for this wonderful history. It is good to be reminded how hard so many people worked to protect the land at Malabar up to this point. Now it is up to us to continue their mission. Eric Miller

LikeLike

Very well-said, Tim. A persuasive reminder that the Malabar Farm forests are indeed something precious deserving of protection for enjoyment by future generations.

LikeLike

Tim, Thank you for a well written, documented and communicated article in regards to Louis Bromfield, Malabar Farm it’s forest land and the need to preserve and protect this treasure located right here in Richland County, Ohio for future generations. Conservation and a concern for preservation must be paramount for its protection and enjoyment,Thanks again for such an informative article.

LikeLike

Really fascinating tribute and beautiful video! We needed to fight to save our planet and its natural spaces in order to save ourselves and our children–and still do. If not, the 100,000 year experiment of homo sapiens may eventually come to an end. Species come and go frequently and we are no exception….. If we had followed the Native American mantra, “As much as possible, live in harmony with everyone and everything,” we wouldn’t have found ourselves in our present dire straits……3/20

LikeLike

Thank you for your wonderful article about Malabar Farm. I have many memories of Malabar. In 1964, Goodyear Tire and Rubber moved to Mansfield to built up their Agricultural division for them. The Bromfield family still owned the farm, I changed all the tractor tires to the newer Goodyear Super-Torque rear drive tires for Goodyear experimental studies.

Also, my mother Sue Pamer would serve Louis Bromfield lunch or dinner when ever he would visit the Burton Preston family home.

LikeLike

Thanks Tim. Every island of sanctuary in our world is vulnerable to what is going on around it. Thank you for reminding us just have important it is to save our island from ill conceived land treatment on its borders.

LikeLike

Hi Tim! Do you know how many acres of forest were saved by the $30,000 donated by Doris Duke in the 1950’s? Thanks for the informative article!

LikeLike

[…] create the 100-acre Doris Duke Woods within Malabar Farm State Park in Richland County to honor the heiress’ contributions to conservation at the farm and across the nation. The woods would be in a mature hardwood forest. Timber couldn’t be removed […]

LikeLike

[…] create the 100-acre Doris Duke Woods within Malabar Farm State Park in Richland County to honor the heiress’ contributions to conservation at the farm and across the nation. The woods would be in a mature hardwood forest. Timber couldn’t be […]

LikeLike