They became friends as two young men who were barely visible in the popular media, drawn to each other by their passion for excellence; and each of them lived to see his friend rise to the very top of his art: Louis Bromfield as a best-selling novelist, and Humphrey Bogart as a movie star of the brightest magnitude.

Their friendship took them through four decades of American popular culture, and to both coasts where spotlights and cameras kept them in headlines, but the high point of all that lifetime of media frenzy took place when they tried to avoid the cameras in the farmlands of Richland County, Ohio.

Their story is told in New York, Hollywood, and Malabar Farm.

New York

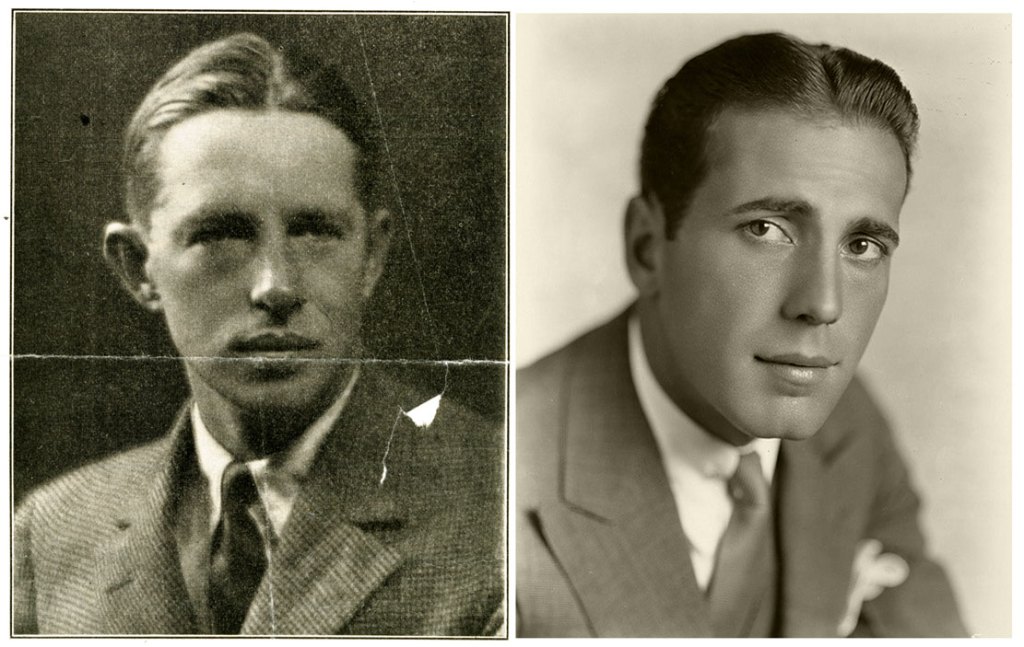

The first intersection of the Bromfield and Bogart legacies took place in Manhattan in 1923.

At that time, Bromfield was moving up the ladder as a writer. In Mansfield, as a kid, his destiny as an author was seeded when he worked for the local newspaper as a reporter. But after the War, as a young man in 1921, he landed in New York working for the Associated Press as a rewrite man. He really didn’t get his own byline until he went to work for Musical American Magazine, but he moved up into a loftier sphere of influence and respect in 1923 when he got his own desk among the founding staff writers of Time Magazine.

His beat at Time was the Music department and they paid him to attend concerts, but his first love in the performing arts was always Theater, and it was his passionate desire to write plays that took him to every show anywhere near Broadway.

That is why on November 26, he was seated at a new comedy opening at the Klaw Theatre called Meet the Wife. The cast had nine actors, but the only one who Bromfield watched on the stage was the kid with the eyes. He played a reporter.

Bromfield instantly bonded with him from clear across the audience. The playbill identified him as Humphrey Bogart.

The two of them met backstage, and the only thing they had in common was time in the service during World War I, but it was enough of an introduction to set them off drinking down 45th Street.

If Bromfield actually thought that he was going to show Bogart a good time around New York because he had been drinking there for several years, he seriously underestimated his new friend’s imagination, resources and connections. Bogart had grown up in Manhattan. He was able to take Bromfield places the Mansfield boy only imagined existed.

In the next years, when Bromfield published stories of Manhattan Prohibition, speakeasies, gangsters and good-time girls, most of the settings and characters of those stories were based on his adventures on the town with Humphrey Bogart.

In fact, when Bogart starred in the Warner Brothers 1940 hit movie, It All Came True, based on a Bromfield story, he was filmed in a fictional New York boarding house not much different than one he and Bromfield had visited in the 1920s.

Louis Bromfield (1896-1956); Humphrey Bogart (1899-1957)

It would be difficult to overstate just how important each of these men was in the success of the other.

Bogart’s influence in providing Bromfield with source material for his writing went beyond speakeasies and gangsters. The level of New York society where Bogart grew up had lace curtains, household servants and private schools. Aside from night club madams, he introduced Bromfield to families that had been comfortably rich for generations.

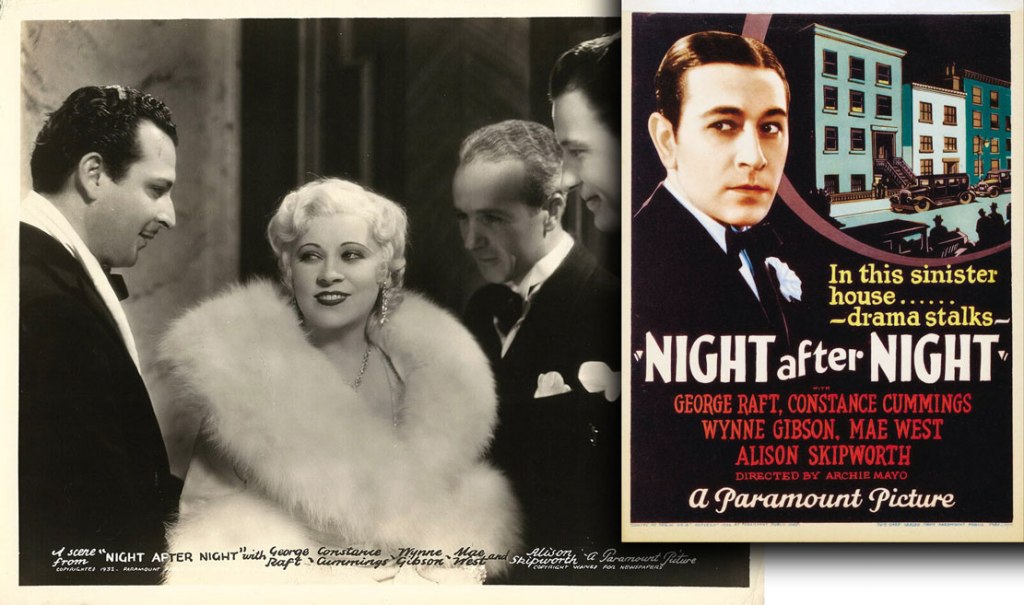

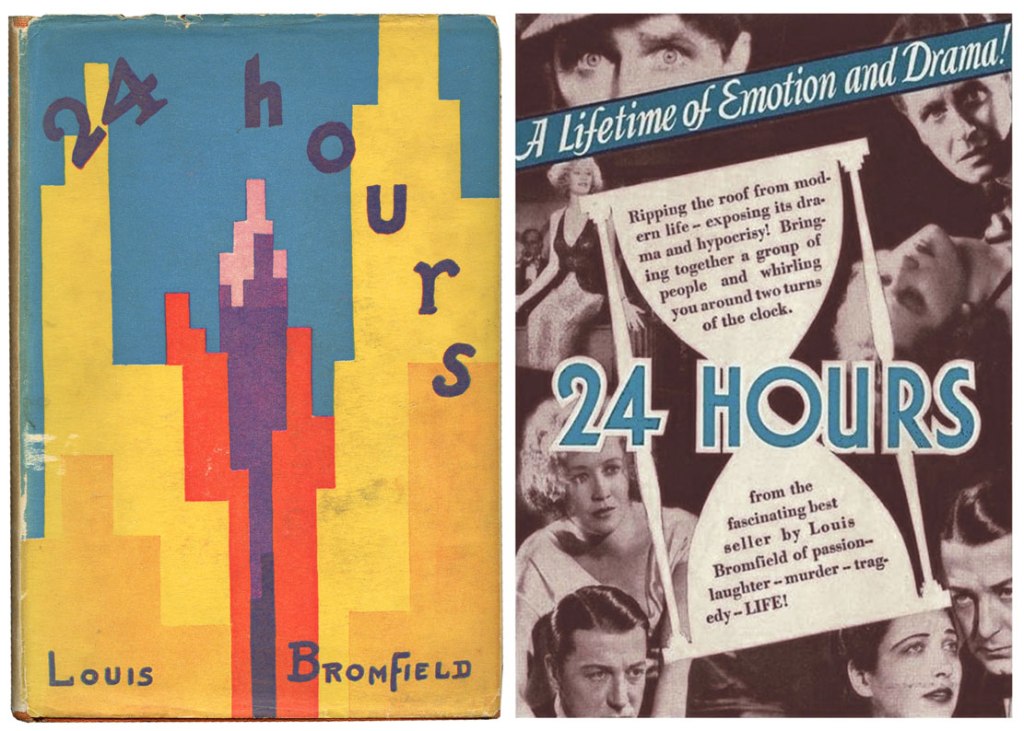

Bromfield’s first novel about New York was an exploration of all the various tiers of society that he and Bogart had partied through in the 1920s. The title of the book was 24 Hours, and, besides being a best-selling novel, it was the first of Bromfield’s works to become a major motion picture. It was his New York book that took him to Hollywood.

And once there, Bromfield could open doors for Bogart.

Bromfield had experience writing for filmmakers in Hollywood before 1930, but this was the first of his books adapted to the screen. It made him highly sought after by producers.

Hollywood

Bogart’s theater career was sputtering in New York in 1929, so he went to Hollywood to try his luck in the movies. He spent over a year doing small roles but the film industry had no traction for him and he wound up back in Manhattan looking for jobs.

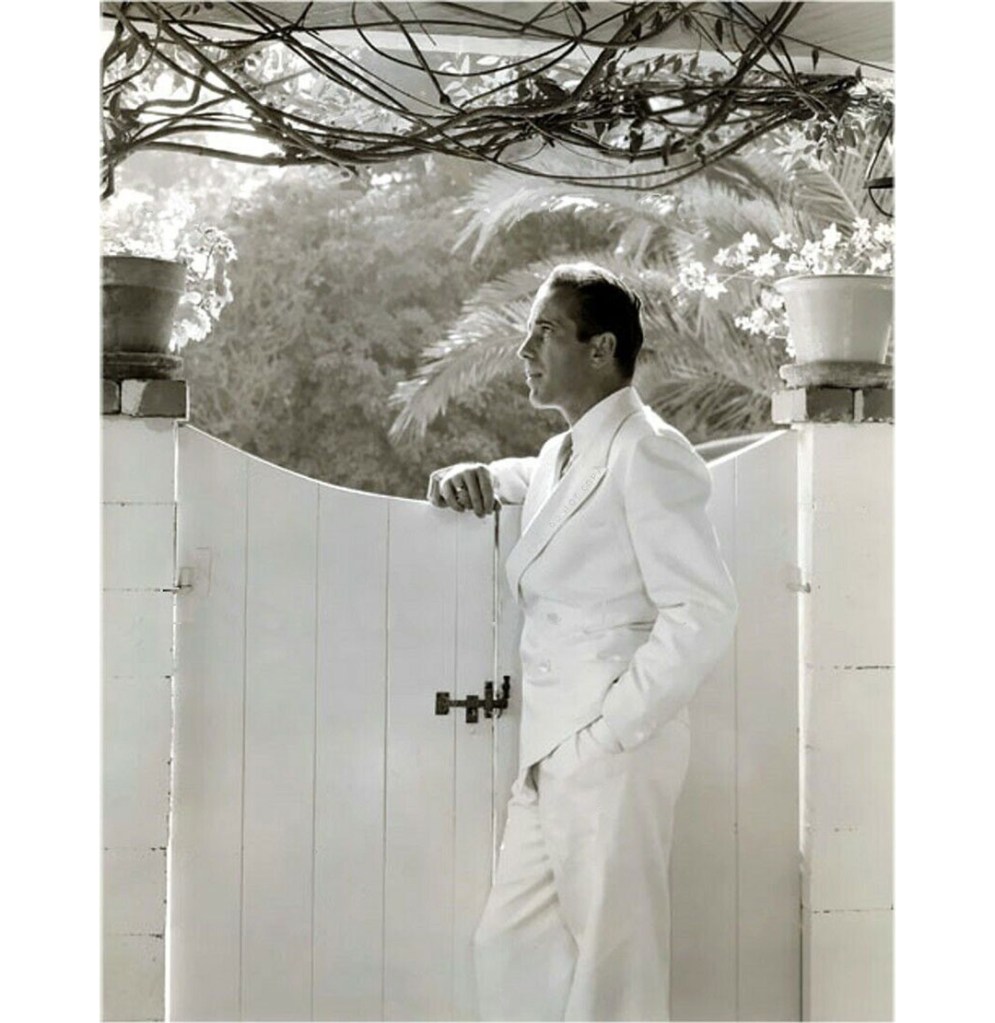

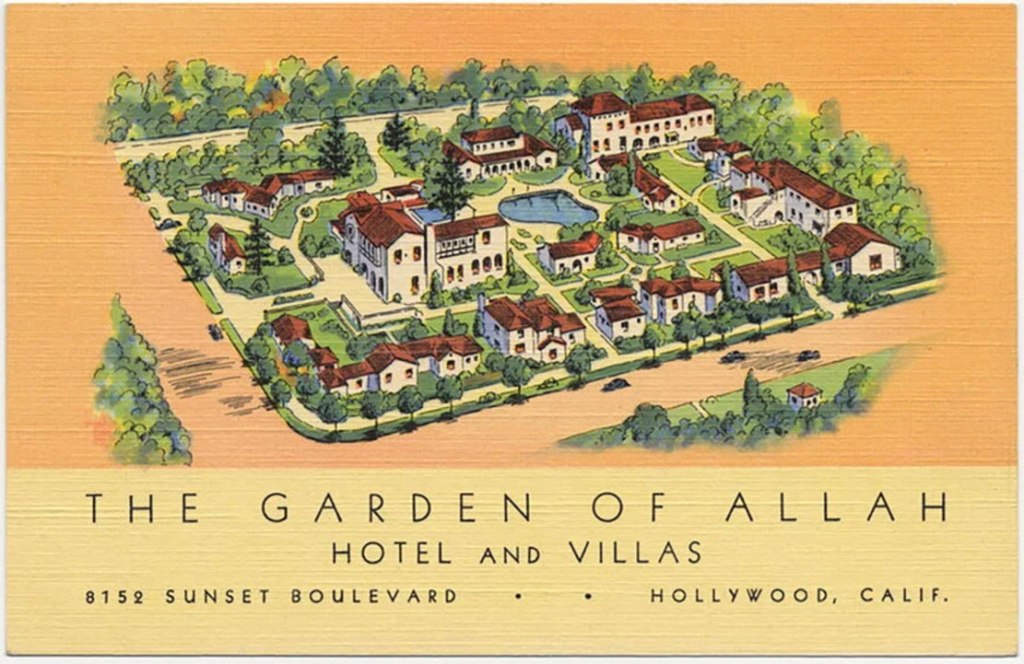

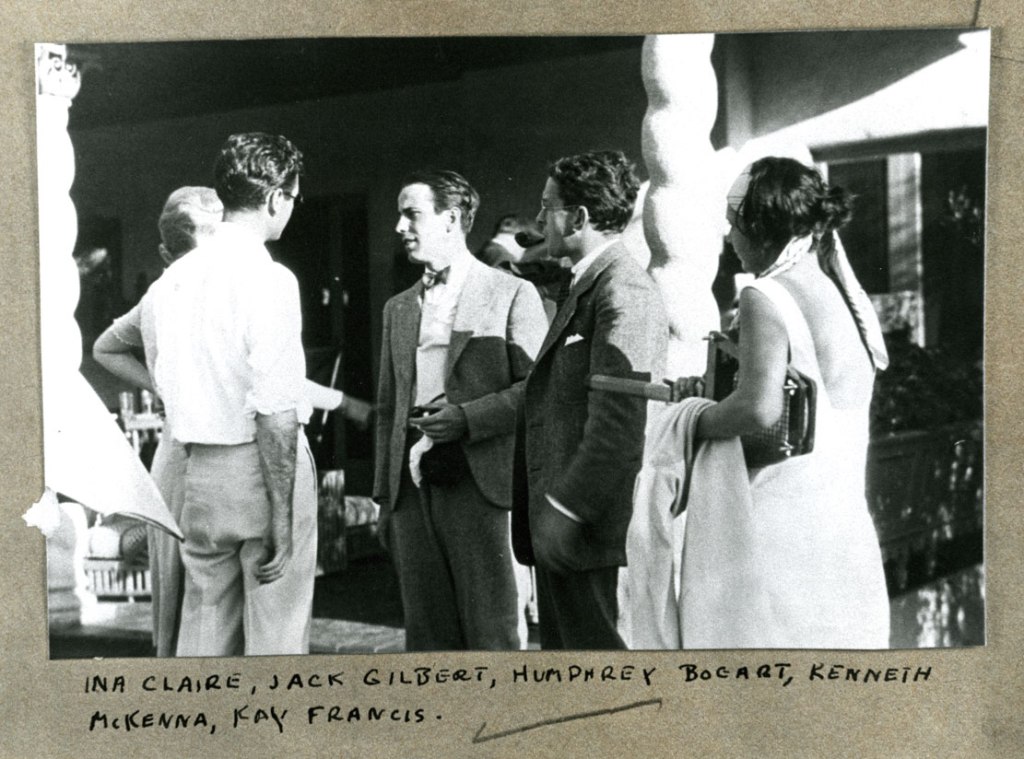

During that same time, Bromfield was in France—at a small town outside of Paris that was his official residence for fourteen years—but he sailed back to America periodically to do stints in Hollywood, writing for the studios. He made his home in West Hollywood on Sunset Boulevard in the Garden of Allah complex, neighboring and partying with leaders of the show business. They all wanted to be associated with the young author whose talent, ambition, energy and luck shone bright as the California sun.

So the day Bogart’s luck finally changed in 1936—when a hit play he starred in was sent into production as a major Hollywood motion picture—Bromfield moved him into the Garden of Allah next door, and introduced him to all the brightest producers, directors and casting agents in town.

When Bromfield sailed back to France, his friend’s future was assured.

Malabar Farm

The two men were perfect complements for each other from the beginning, almost as if by design. Bogie was raised as a spoiled rich kid, frustrated that he was never allowed to get his clothes dirty; Bromfield often went to school covered with mud from the farm, whose personal regret was that he wasn’t raised in high society.

Their deep inner personalities completed one another in this way, and they never lost an opportunity to spend time together. So, when Bromfield moved back to America in 1939 and established Malabar Farm, his guest room was always ready for any chance when Bogart could get away from his hectic city life.

Bromfield even made a gift to his friend of an acre of Malabar land where Bogart could build his own country getaway. Bogart told the Associated Press he planned to create a log cabin bungalow ‘down the creek’ where he could relax between movies.

Often the News-Journal caught wind that Bogie was in town, and let word slip so that reporters from all over the state converged on the Big House. Bogart, however, had come to the country to get away from all that. One time in 1942, a news writer cornered Bogart at the farm and thought he would get an exclusive interview because Bromfield invited him in to the house for drinks. When he was seated in the living room, Bromfield and Bogart laid out the rules: the reporter was welcome to stay and drink all night if he wanted, but the first time he posed a question they were tossing him out the door.

When Bogart wasn’t on site in Europe, or on the set in Hollywood, he was often at Bromfield’s, and sometimes he brought his wife, Mayo. She was welcome until she started breaking things in combat with Bogie. Mary Bromfield had a collection of ceramic roosters, and she learned to put her favorite pieces inside a cabinet whenever Mayo was having a dramatic mood.

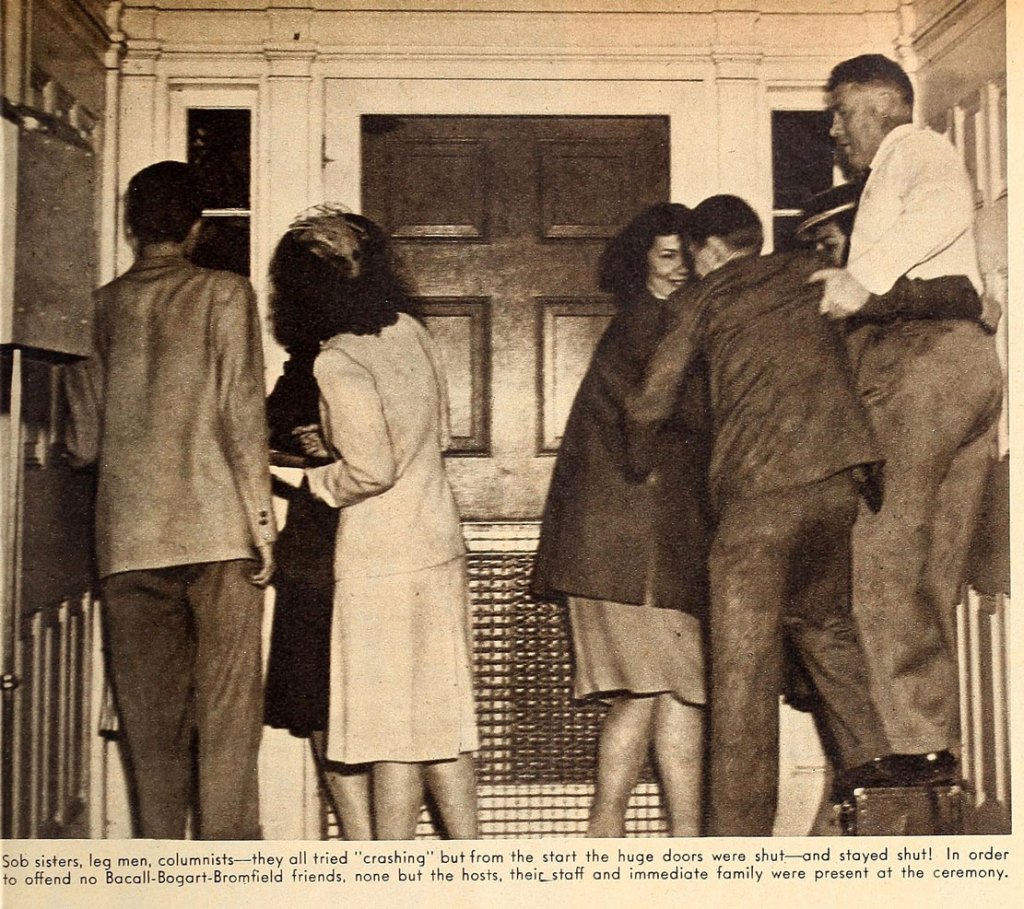

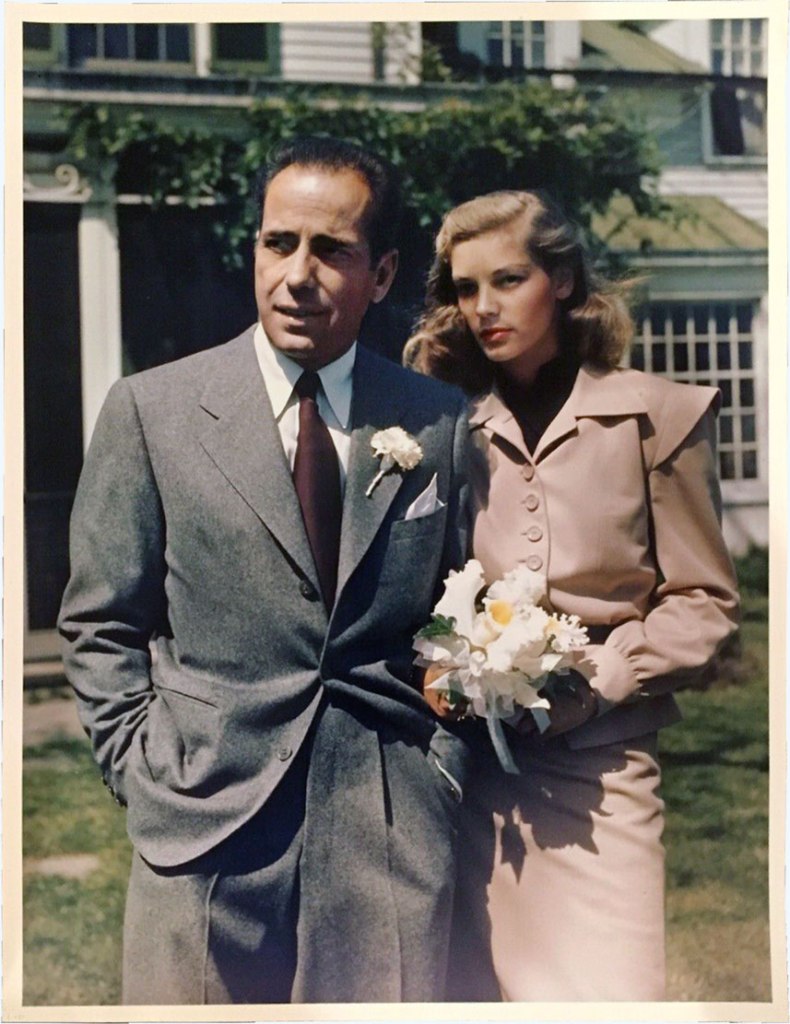

It was no secret in the media when Bogart and Mayo split up, and then headlines were carefully tracking Bogart and Bacall once it seemed possible that their marriage could be in the offing. For two such public figures it was not easy to escape cameras in New York or Los Angeles, so they began meeting at Malabar. The Bromfields’ chauffeur was burning up the road between Pleasant Valley and Union Station in Mansfield meeting trains from both coasts. So far out in the country, it seemed a safe bet they could have a wedding at the farm without being besieged by newshounds and film crews.

The word leaked, though, and one reporter from Los Angeles wrote his account of racing across the nation on a train to Ohio thinking he had an exclusive scoop, only to discover that the train was loaded with nothing but cameras and news people. When he arrived at the farm there were nearly 300 cars being held out on the road by a full company of Richland County Sheriff’s deputies.

Nobody but family and friends got inside the house, yet the wedding was well documented in newspapers, cinema news reels, and fan magazines. There were certain small details that only eye witnesses could tell about: insiders knew that Bromfield’s huge boxer Prince strode into the middle of the ceremony and plopped himself down on the rug at the feet of the Judge.

All of the media coverage documented that Bromfield was Bogart’s Best Man, but as the decades of popular culture wax and wane it is largely forgotten that Bromfield was also Bogart’s Best Friend.

Post Script:

Afterthought:

It was about 11 miles of dirt road before the city pavement started, so Bromfield paid to have a special thoroughfare laid from his farm to the end of Diamond Street. It was a concrete slab wide enough for his car. Everyone was welcome to use it, but they had to hit the dirt when they saw the Bromfield Pontiac coming.

Years later, the road was made two lanes by adding asphalt to both sides of the Bromfield highway; and ever since then the pavement has cracked and worn differently than any other road in the county because really, it has always been just his driveway.