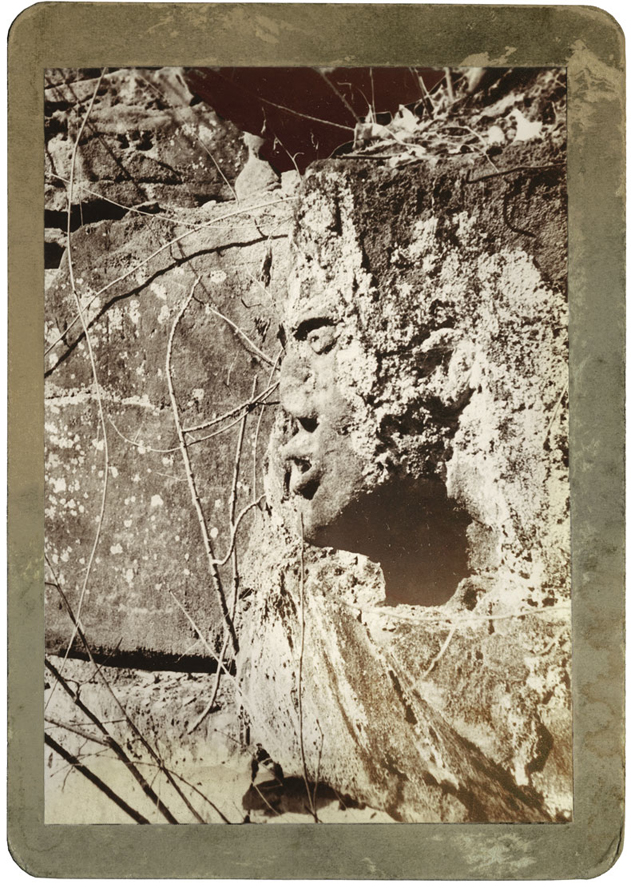

There is a stone face carved into a cliff overlooking Fleming Falls. His singing countenance has gazed down on the leaping stream for so long that mosses and soft lichens have given his sandstone skin an organic patina which defies time. So, it is difficult to know just exactly how long ago the sculpting artist wrought human character from ancient bedrock.

These are the clues we have so far.

1970

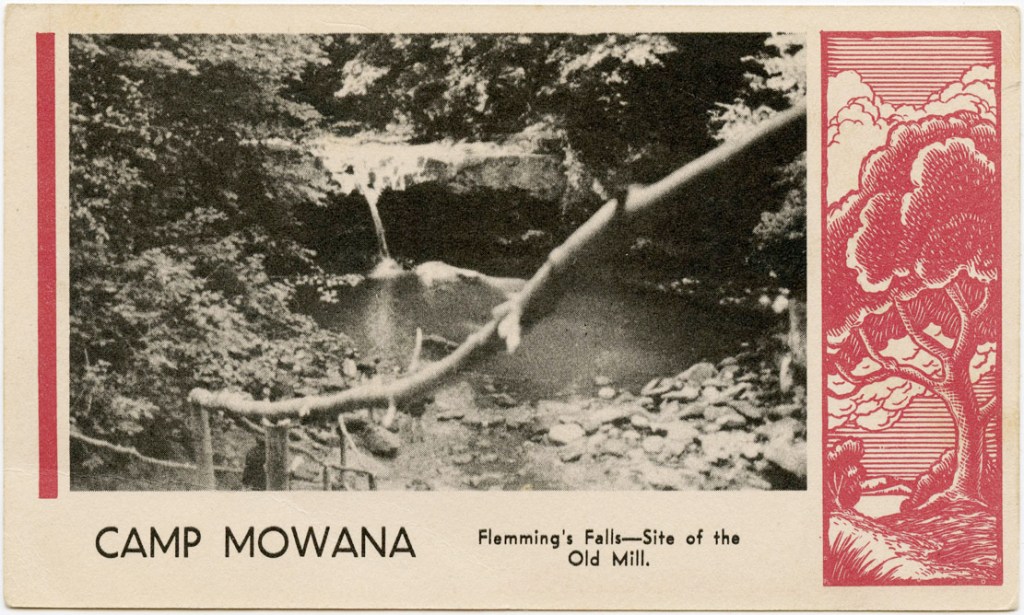

It has been 50 years since I first met the Singing Man at Fleming Falls and began researching his origins. At that time, the falls belonged to Camp Mowana, and, while the guardian Lutheran church camp folks were glad enough to show off the landmark sculpture, they had no exact sense of how it got there.

They could only assume it had been carved into the cliff face during the decades before Mowana, when the falls belonged to the Boy Scout camp.

This is an easy assumption because there are at least two other face carvings in the nearby rock—no doubt inspired by the Singing Man— which definitely show the influence of Boy Scout culture. One of the imitators’ carvings wears a feathered Indian headdress like a Scouting ceremony. Both of them are brazenly signed like self-obsessed teenagers engaged in public park graffiti.

These two alternate faces can definitely be dated circa 1925-1939.

The Singing Man, however, is clearly of a more elevated integrity of design and purpose.

1925

Fifty years ago, it was not difficult to find older Scoutmasters who had been young men in the 1920s and ‘30s, who had spent time at the Fleming Falls Scout Camp.

The ones I talked with agreed, the general assumption back then was that the Singing Man had been sculpted into the cliff by a tribal artist of either the Wyandot, Lenape, or Shawnee nation back when those peoples were in residence in Richland County in the 1700s and 1800s.

Further, it was told around the campfire that the chant which the Singing Man cried out was a protective spell invoking the Great Spirit to watch over the Falls. To medicine men of the Lenape, the leaping waters of a falls are a communication between the Great Spirit above to the dependent Earth below; and a waterfall represents—not merely symbolically, but in actuality—the Blessings and outpouring of life to all the beings in the community, be they plant, mineral, animal or Lenape.

This, the story went, serves to explain what happened to the Fleming Mill that stood on the falls in the 1840s: it was washed out of the way by a wild spring flood, brought about by the Fall’s guardian, in order to set free the falling water.

It is a nice story, and it would seem to explain a lot. Which is exactly what Scout tales around the campfire are supposed to do.

The Scoutmasters agreed that the tale was like a lot of those Scout stories: improvised for an occasion, but lingering on with its own life long afterward.

There could easily be some kind of truth behind it, however, and it provides grist for the mill of further research.

For one thing, the Scout tale does seem to presuppose that the Singing Man was old when the Scouts got there in 1925.

1890

Eventually in my research, I was finally able to find proof that the Singing Man existed well before the Boy Scouts.

About twenty years ago I was given access to scan photos from a collection of images that had once belonged to a local historian who wrote columns for the Mansfield newspaper. The old photos were sorted into folders by subjects, and there was an odd repository in the back of the file drawer filled with miscellaneous pictures no one could identify.

I had no problem identifying one of them: it was the Singing Man, and though not labeled as such, a carefully inked inscription on the back dated the photo to 1890.

The Fleming Falls chasm, cliffs and waterfalls had been a popular picnic grounds that was well attended for generations prior to 1890. The site is documented to have been a destination as early as the 1830s, so it is a bit perplexing that decades of tourists, and historians familiar with the area, would fail to mention the Singing Man.

On the other hand, I have never met anyone who noticed the face in the cliff wall until it was pointed out to them. Even people who know of its presence often have to search for it.

We cannot assume that anyone before 1890 who saw the sculpted face thought to draw attention to it.

1785

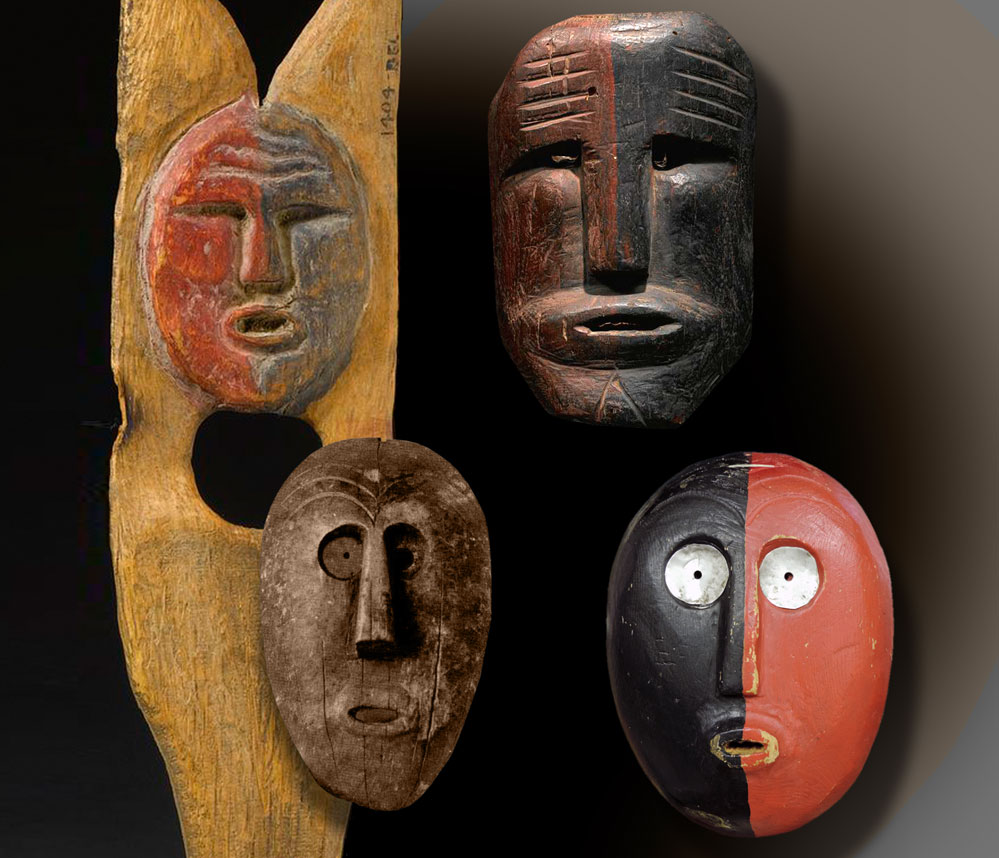

It is entirely possible that the Singing Man did, as the Scouts hoped, originate from an artist membered of the historic tribes who lived in the area from roughly 1760 to 1820. Each of these tribal cultures—Wyandot, Lenape, and Shawnee—has a tradition of human facial representation in carved masks. The Singing Man would have been a familiar motif in their ceremonies and mythology.

100 BCE

Far more probable—at least from the standpoint of opportunity—is that the Singing Man was carved by an artist of the Adena/Hopewell era of prehistory, who had over a thousand years in which to find the Falls, and hallow the sacred grounds with an earthen mask.

There is good reason to think this may be so.

The famous Adena Pipe—which has been recognized as the official Ohio State Artifact—bears a curious resemblance to the Singing Man. The pipe, which was unearthed from the Adena Mound in 1901, is around 2,000 years old. There is no way of knowing exactly what the character portrayed by the Pipe meant iconographically to the Adena people, but he shares with the Singing Man one essential feature: the need to sing.

Not only is this man singing, his legs are flexed for dance and he wears a feathered tail for soaring like a hawk. Clearly, he expresses a sense of being in the world that is best exemplified by a character whose most notable sculpted attributes indicate celebration: singing and dancing.

Timeless

At our current position on the timeline there is probably no way of determining for certain how old the Singing Man is, or in which cultural paradigm of Richland County history the artist lived, because even for experts in archaeology and anthropology the distant past is almost wholly conjectural.

What we have, though, is the unambiguous fact of his face: calling to us from the past, only to be heard within the chorus of waters rushing over the sandstone ledge. His very presence speaks of the reverence with which another distant era regarded the beauty of the Falls—enough to hallow the face of the cliff, the face of the planet, with a face of humanity in song.

For more background on Fleming Falls:

Destination Fleming Falls: 1913