Preamble

When in the course of human events was doing the right thing not only dangerous, but literally illegal?

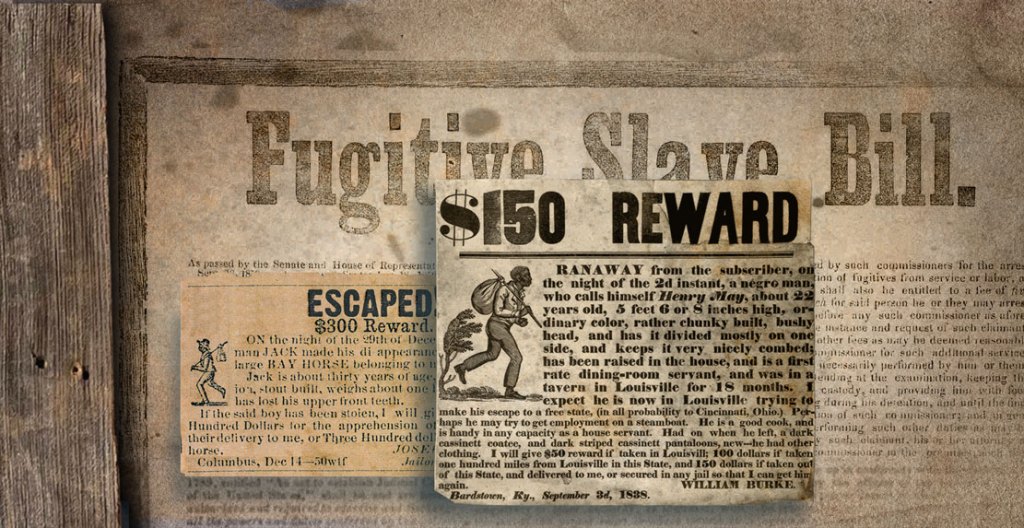

That would be during the decade leading up to America’s Civil War: when U.S. Marshals could arrest anyone who helped a Black person fleeing away from plantations in the South where it was believed—and the law insisted—that Black people were the “property” of someone else.

Richland County stands second to none among the populations of Ohio and the nation in courageous undertakings to assist fleeing enslaved peoples on their way to freedom during that dangerous era of history. It is a matter of record that Stations of the Underground Railroad located along the roads of our community gave assistance to many thousands of desperate refugees by defying the law.

For a quick overview of the fugitive slave catastrophe in America at that time, and the Richland County solution, here is a 9-minute documentary prepared in 2008 as an introduction for participants in Mansfield’s Bicentennial Underground Railroad Walk.

Recording the History

Several decades after those dangerous years, when historians were looking back to gather information about the Underground Railroad, there were any number of people in Richland County who could easily identify who the Conductors had been. It was common knowledge to those paying attention.

Identification was a matter of relatively easy public access, because all the local Conductors were outspoken members of the Richland County chapter of the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society. In 1836, when they held a convention in Granville and published their proceedings, it was documented in print that Benjamin Gass was the secretary of the local society which numbered 22 members. Any one of those members could conceivably help out in the logistics of transporting slaves north.

The challenge for the Conductors during the critical years of breaking the law was not maintaining anonymity, but, rather, moving runaways through public thoroughfares with enough cunning to keep from getting caught at it when U.S. Marshals and Kentucky slave catchers had no difficulty finding out who the Conductors were.

That is why most of the Conductors we know about maintained some kind of ingenious secret hiding place:

I first read his account long ago and have puzzled over it all these years until recently. There was not anyone in all Troy Township named Lions.

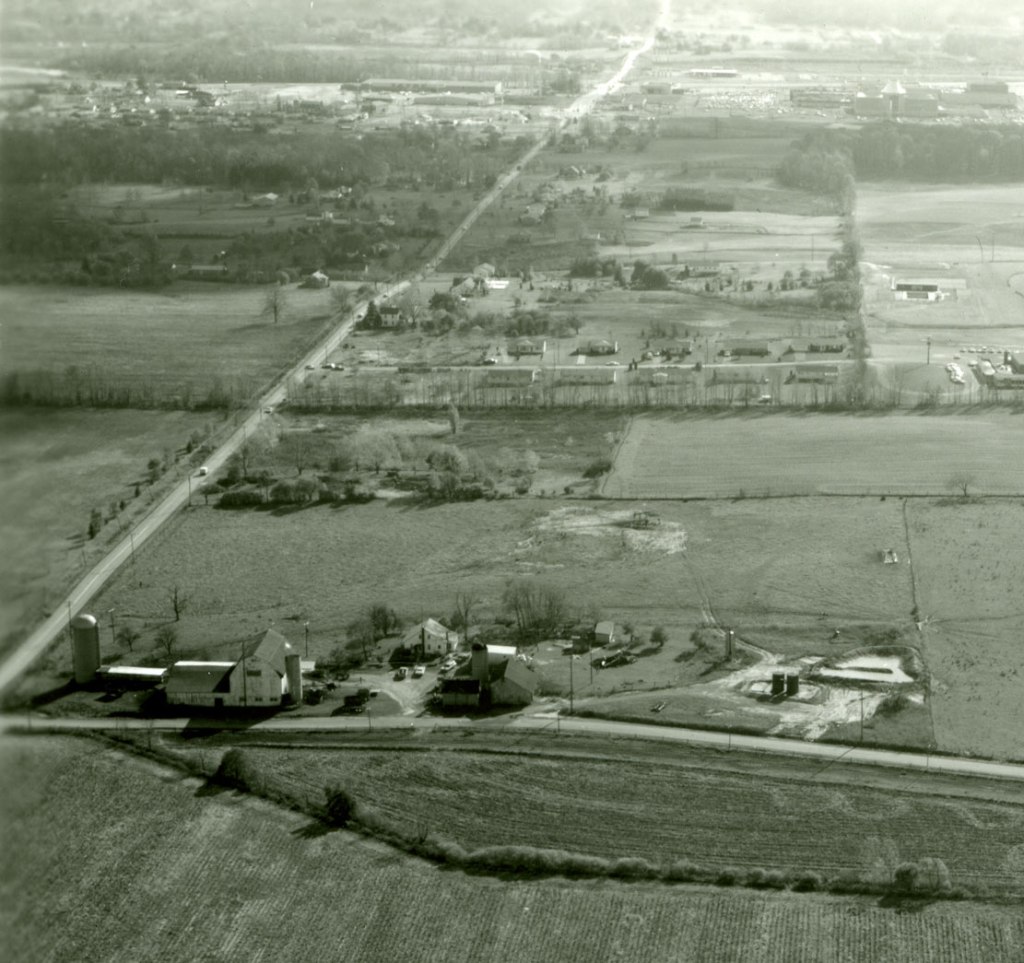

The most prominent station near Lexington, and the most likely Conductor who Gideon would have encountered was James Gass, whose house still stands in much the same semblance as it did in the 1840s when Gideon found it on the Springmill Road in the middle of the night.

I was pondering this again one day when suddenly, after all these years, it finally made sense. At fifteen years old, what made the biggest impression on Gideon was the same thing that impressed me when I was fifteen: the lions.

The size of the fireplace had an alternate purpose, however, because the rear wall rose only just above the height of the mantel and a person wanting to hide could clamber over that wall into a secret chamber behind the room.

By the time I saw the fireplace in the 1970s, its front was covered over to leave only space for a wood stove, but in the dugout basement the stonework of the chimney still gave clear evidence of the hidden compartment.

Contacts and Corridors

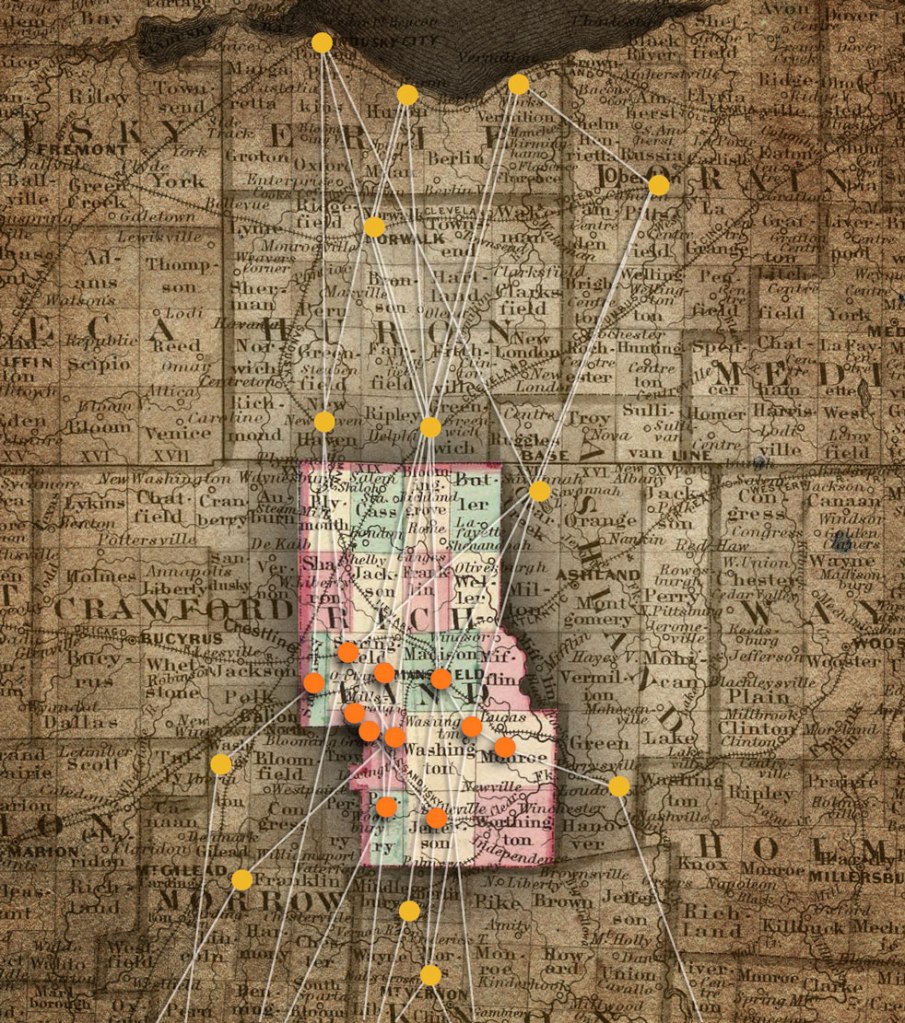

Neighboring Conductors knew one another in order to be of assistance in case of emergency, should slave catchers or U.S. Marshals show up on the trail of runaways, but their more important contacts were those Conductors south of the County who delivered midnight cargo to their door, and those north of here closer to Lake Erie.

Communication back then was no faster than a horse could travel in the decades of 1830 to 1860, so most Station stops occurred unannounced and without much noise. John Finney’s daughter wrote, “The coming of fugitives was always something exciting at our house. We would be waked in the night by the barking of dogs. To the inquiry of “who’s there?” the answer would be, “Friends.”

“Immediately in the dark hours everyone was fed: fugitives & Conductors. The Conductors would then say goodbye, and the passengers would be disposed for the night in a spare bedroom, the garret, or the barn.”

Depending on how many arrived, there were always spontaneous variables as to how and how soon they would be moved on up the network. One group of formerly enslaved Alabama field hands offered to help Finney get in his crops before they departed. Years later, neighbors documented commonly seeing Black folks around the Finney place doing chores.

Crossroads of Freedom’s Trails

Each Conductor maintained relations primarily with their own cohorts north and south, and had little knowledge of their neighboring Conductor’s traffic. Because of that, there is no way to adequately estimate how many Black people came through Richland County from 1830 to 1863. John Finney’s daughter wrote in later life that she could personally assert her father was responsible for the assistance of at least three thousand runaways during the twenty-eight years he was involved.

With at least a dozen highly active Conductors in our area, there could have been easily upwards of 25,000 footprints of former slaves on the dusty roads of Richland County—more than twice the population of Mansfield at the time.

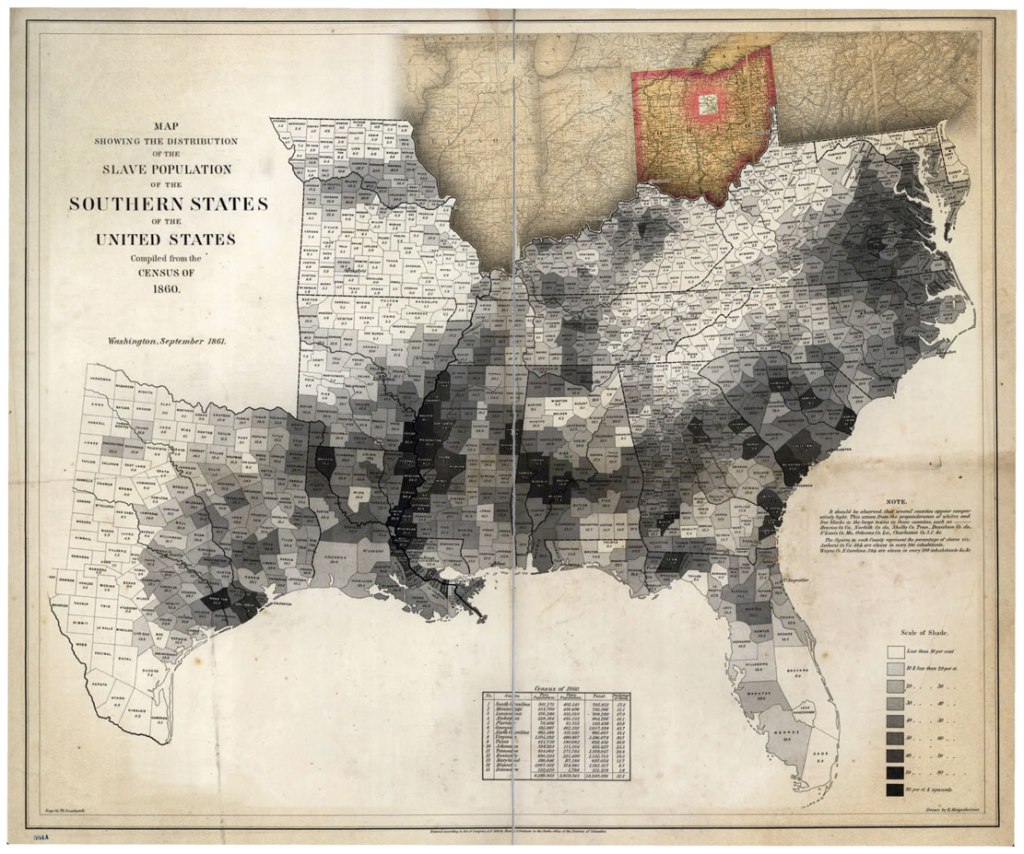

Ohio, and Richland County, being the shortest access to the northern border of the U.S., drew fugitives from a number of Southern states including most often Alabama, Tennessee, South Carolina, and Kentucky.

One Last Word about that Famous Finney Prayer Incident

The story of John Finney and the interminable prayer has been told many, many times in local, regional, and national history books about the Underground Railroad. The tale always winds up with the fugitives safely away, and Finney chuckling under his breath, but that was not actually the end of the story. Further research documents a whole added dimension to the incident that could nearly have turned the Fugitive Slave Law on its end.

This episode began when a Conductor friend of Finney’s delivered to him a wagonload of six fugitive men and five women and children, knowing that there was a posse of slave catchers hot on their tail. No sooner had Finney got the refugees out of sight when men in eager pursuit raced up the road fully aware that the runaways they sought were on Finney’s grounds.

Finney demanded a search warrant, as is often recounted, and when the bounty hunters sent three men into Mansfield to get a writ from the Sheriff, Finney also dispatched a messenger to town as well to sound an alarm.

The whole breakfast-and-prayer scene took place as narrated in the accompanying documentary, but immediately afterward there were a number of scenes enacted which have been edited from the popular version.

The warrant arrived from Mansfield, but swiftly behind those riders came a hustling team of Finney’s colleagues, “armed with double barreled guns, pistols, bludgeons, &c., to prevent the Blacks being taken.”

It is well known that Finney’s rambling prayer allowed the fugitives time to escape to the woods, but what failed to be reported in the entertaining anecdote is that when the armed band came into the barn to confront the Kentucky slave chasing would-be captors, a scene took place that completely flipped the narrative of Underground Railroad assumptions.

They “arrested the slaveholders for attempted kidnaping.”

It was a bold move, and one potentially consequential enough to shake the entire nation. But there is a reason why this part of the story didn’t make it to the history books. While the slave catchers cooled their heels in the Mansfield jail, a very similar case was being tried in Washington DC, and everyone was watching the news eagerly to see what kind of legal precedent would come of it.

Unfortunately for the Richland heroes, the DC judge decided that kidnaping involves people and slaves were chattel no different from livestock. That was the end of it. There wasn’t much chance any conservative Mansfield judge would take that tipsy boat out upstream into the raging torrent of popular opinion.

So the Mansfield humanitarians had to drop their case.

Not-So-Underground Activism

For people engaged in “secret” activities, some of the Conductors were anything but silent. One of them was Joseph Roe, who was not only a right-hand conspirator with Finney and Gass in moving thousands of fugitives through Richland County, but was also a prominent local voice for abolishing slavery in America.

One winter night in 1858, Roe had delivered to his door a runaway fugitive who had made it to Richland County all the way from New Orleans. Snow and ice were making the roads treacherous, so they agreed to wait out the storm before proceeding on northwards.

It gave them time to get to know each other.

And then, greatly moved by his guest’s tale, Roe asked if the man would consent to speak to the community.

It was at the United Presbyterian Church in Ontario where the Black stranger delivered his story.

He had been born in Kentucky within sight of the Ohio River, and yet his runaway journey to freedom was begun as far deep in the south as New Orleans. This was because he had been sold eleven times in his career and lived in four states. He never lasted too long on any one plantation because sooner or later they found out he could read and write.

Literacy made him a threat to the whole system of Southern slave holding, which absolutely relied for its existence on fear born of ignorance, superstition and the inability of slaves to organize. An African American who could read and write challenged their sense of superiority.

The townsfolk of Ontario were greatly moved. They took up a healthy collection to help the man begin a new life in Canada. And that was before Joseph Roe asked his guest to remove his shirt and show the crowd his back. It looked like a map of all the miles between Kentucky and New Orleans.

When an account of this church meeting was written a dozen years later, the writer said the Black man’s story did not recruit any Conductors to the service of the Underground Railroad, but it did make the citizens of Springfield Township appreciate the meaning and importance of the Civil War when it began three years later.

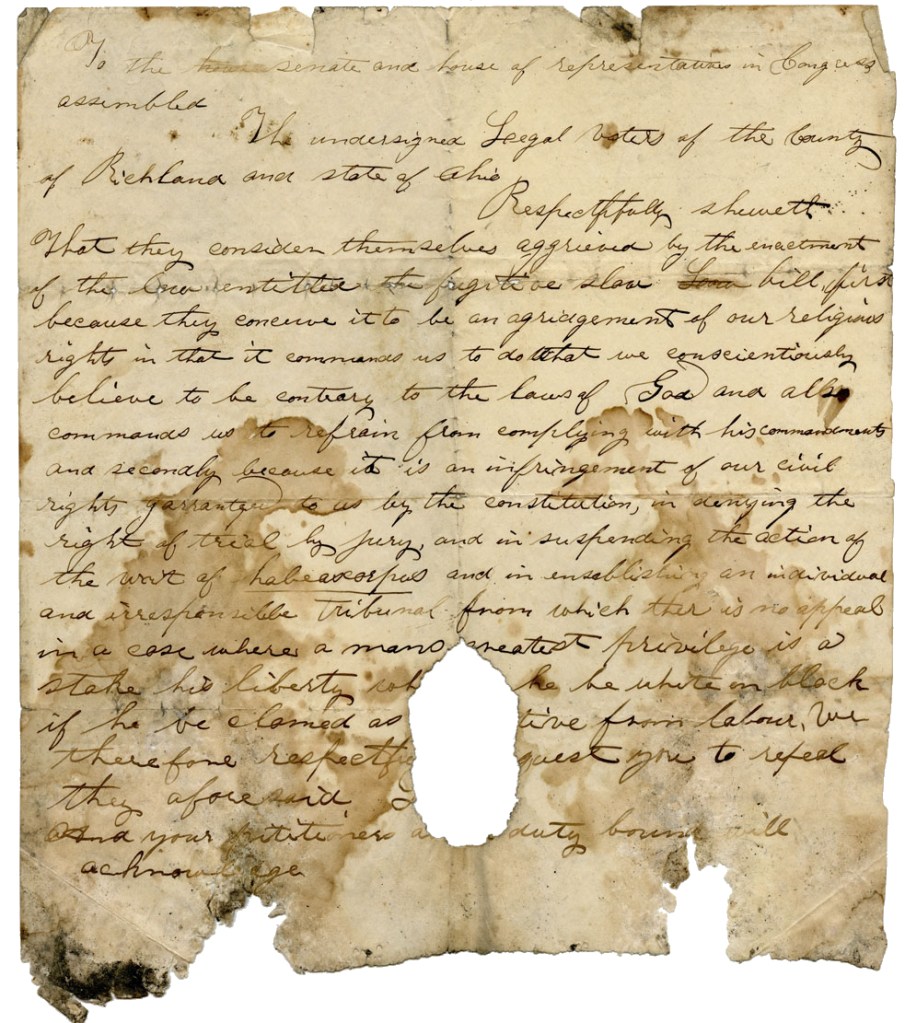

The petition seen below was written in 1850, but it was not the first sent from Richland County. Official Congressional documentation bound in the Library of Congress can be found that reads, Petition from the Citizens of Richland County Ohio to the United States Senate, “Praying the abolition of Slavery in the United States.” Dated Monday January 22, 1838.

“The undersigned Legal voters of the County of Richland

Respectfully sheweth

That they consider themselves aggrieved by the enactment of the fugitive slave bill

because they conceive it to be an abridgment of our religious rights in that it commands us to do what we conscientiously believe to be contrary to the laws of God and also commands us to refrain from complying with his commandments

The Ultimate Context

There is a quote from Joseph Roe to conclude this particular article, but it helps to know the context from which it derived:

Roe had sold a very nice plow to a man from Huron, and when the buyer came to pick it up, Roe arranged to have the wagon back up to his barn. As soon as the beautiful and expensive plow was firmly secured in the wagon, Roe threw in a couple blankets under which two Black fugitives quickly hid themselves.

The man from Huron was furious. He ranted for a while before Roe made it clear that the plow was not leaving without the two men. Once the wagon arrived in Huron, he explained, the men knew where to go.

The buyer ultimately had no choice and grudgingly agreed to the arrangement.

Roe assumed he would never hear from the Huron man again, but then chanced to have an encounter with him some months later. The man from Huron, he said, had not changed his political views, but he had radically revised his attitude toward the Fugitive Slave Law.

Interviewed in 1885, Joseph Roe said of his Huron friend, “There are none so mean of heart who could ever consent to the keeping of slaves if ever once they have ridden all night in a wagon with these men and women, listening to their stories, hearing their children murmur, seeing their tears.”

More background on Richland’s Underground Railroad:

Legends of the Clear Fork: Sam McCluer and his Cornfield

Underground Railroad 1854: Unscheduled Cargo in Shelby

The Underground Railroad Part 2: Mansfield’s Black Conductor

[…] The Underground Railroad Part 1: Richland County […]

LikeLike