Mansfield had a Conductor of the Underground Railroad who never got into the history books. Maybe because he was Black. Maybe because he didn’t talk about it afterwards. Maybe because he was good enough at it to not be noticed. Probably all three.

What He Was Up Against

From our vantage point on the Timeline, it seems self-evident that putting an end to slavery by helping slaves escape their involuntary servitude was a just and righteous activity—certainly much less destructive than ending slavery by Civil War. But not everyone around Richland County felt that way at the time. In fact, the majority of voters here repeatedly favored candidates who fought for the rights of Southerners to own and sell and exploit slaves.

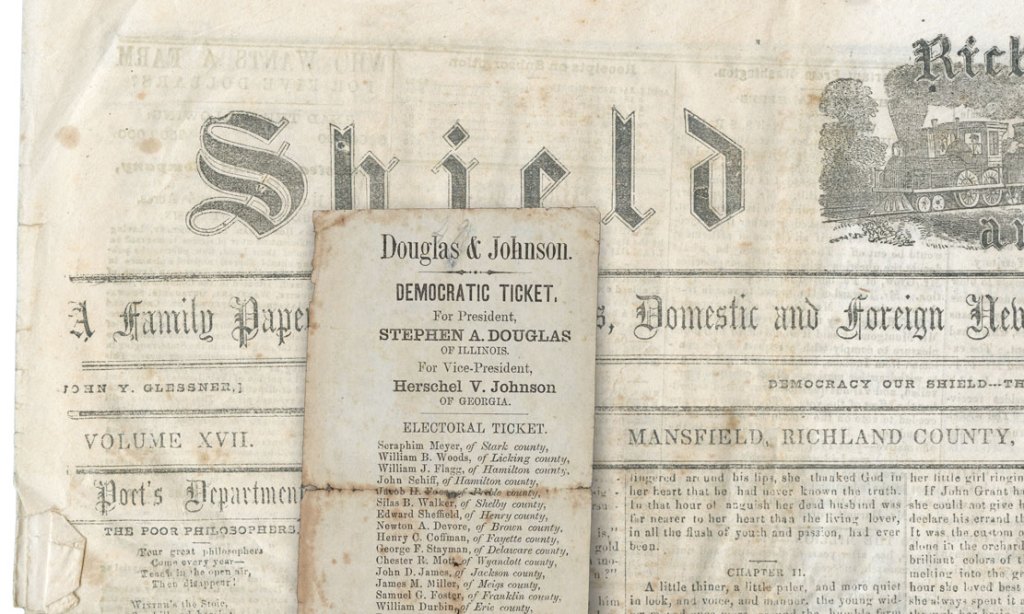

Mansfield had two newspapers before the Civil War—one for each opposing American political faction—each paper clearly opposite the other on the question of slavery. The more established of the two news sources was the Richland Shield & Banner, which was owned, edited and sold by John Glessner, Mansfield’s most stridently bigoted racist.

The stories and opinions he published every week in Mansfield gave readers of the Shield a continual stream of rabid racist invective in the most vulgar language and illustrations he could produce. There are an unbelievable array of appalling examples that could be shown here in evidence, but it is too degrading to give those sentiments life again by breathing words into them after their newspapers, their readers, and their writer himself have all finally turned to dust.

Setting aside, for a moment, the cruel words, it is enough to note the purposes to which he used those words like weapons. In 1842, Glessner raised a petition in Richland County demanding that the State Legislature revoke the charter of Oberlin College because they admitted Black students. Oberlin, he said, was “poisoning the minds of youth.”

As testimony within the document, he actually made reference to the Underground Railroad. In those years when we generally think of the transport of fugitives as a secret undertaking, he asserted that “treasonable abolitionists have established many routes throughout this State along which they convey runaway slaves to Canada. All these negro thoroughfares point toward Oberlin.”

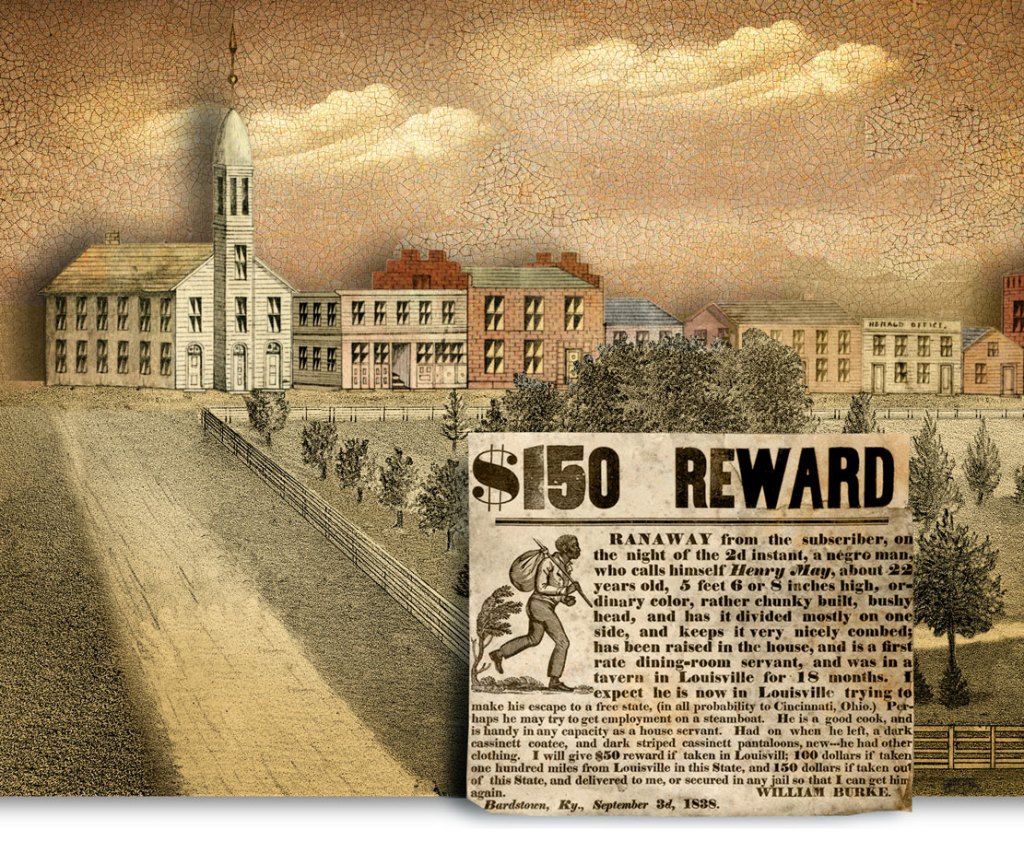

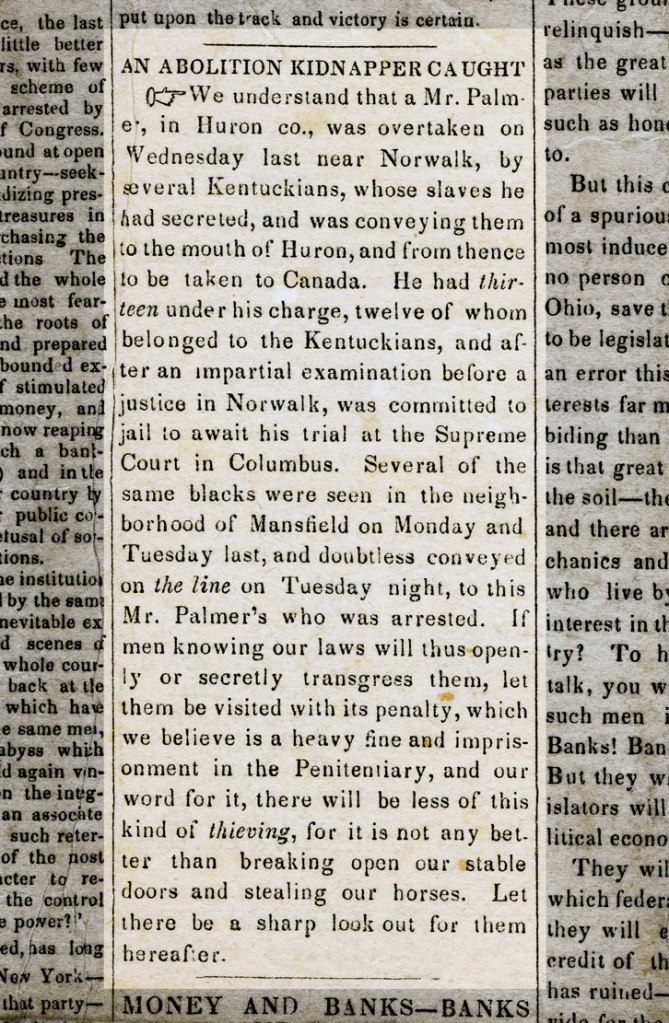

Studying the newspapers of the time, it is clear that even as furtive as the “underground” activities were, they were really no secret. Reading this news clipping about a Conductor in Norwalk who got caught, it is obvious the reporter was fully aware of fugitive traffic through Mansfield. He says, “Several of the same Blacks were seen in the neighborhood of Mansfield … and doubtless conveyed on the line …”

Glessner asserted that assisting fugitives was “thieving,” and said, “it is not any better than breaking open our stable doors and stealing our horses.”

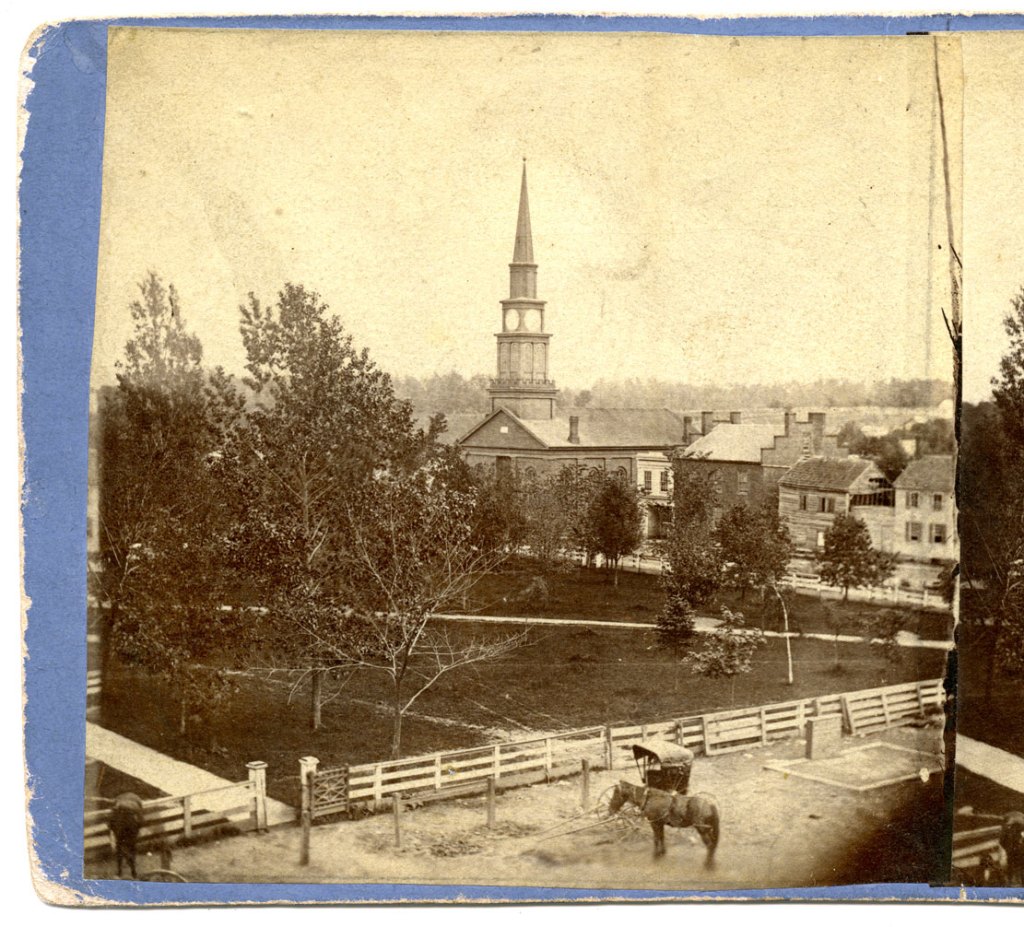

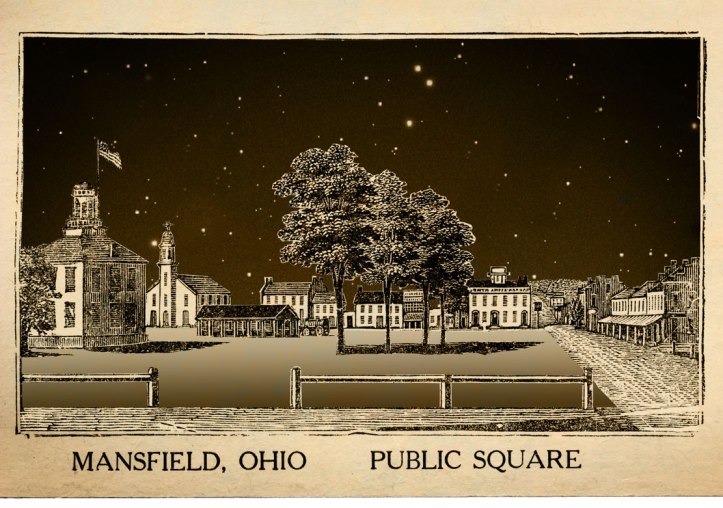

Glessner’s newspaper helped to foster an atmosphere of intolerance and hate in Mansfield. It was a town not readily willing to look away from what they called, “slave stealing,” even within the context of Christian charity. The Presbyterian Church on the Square was targeted a number of times with eggs, rocks through the windows, and obscene words painted on the walls because the minister preached sermons advocating that Africans were intended by God to be loved as one’s neighbors.

The town acquired a bitter reputation of being so fiercely opposed to racial equality that when Frederick Douglass came to town in 1857 to speak of abolishing slavery, his appearance at the Congregational Church was not advertised for fear of evoking public demonstrations of violence and hatred.

In fact, in the documented Underground Railroad activities of a Quaker settlement in Fredericktown, it is clearly noted that in moving fugitives to Greenwich they planned to pass through Mansfield only in the middle of the night because of the city’s fiercely pro-slavery reputation.

Given this legacy of bitterness, it is not surprising there are so few tales of Underground Railroad Conductors within Mansfield. Clearly, no one in town wanted to attract attention.

Untold Legends

So now, with a better understanding of the brittle atmosphere of Mansfield, it is all the more astonishing to realize that there was, indeed, a steady flow of fugitive runaway traffic through town during the last decade of the Fugitive Slave Law. And, even more amazing, that the Conductor who was able to achieve this delicate dance of continual peril was, himself, a Black man.

His name was Isaac Pleasants, and he remains nearly as anonymous today as the men and women he helped to pass through town on their way from slavery to liberty.

Isaac was—at the same time—both the most visible and most invisible person in town. He was a free Black man, and there were few enough of those in the White population of Mansfield that he could easily be identified.

On the other hand, nobody particularly paid him much mind. He had the busiest barber chair on Main Street so he was a fixture of downtown, and, as such, hardly noticed at all. Yet he was there in the background and overheard a great many conversations of influential men of business while they sat in his chair. And those men—the undisputed leaders of the community—trusted him absolutely. They had to. Every day he held a razor to their vulnerable throats.

Isaac Pleasants was so commonly accepted and trusted that it caused no turmoil in the community when he was given charge of a Black Sunday School at the Presbyterian Church. This was the very same church, located prominently on the Square, that had been regularly vandalized before and during the Civil War because of its stance on racial equality.

He established a Sunday School class of recently Americanized Africans, and because they were only newly freed from bondage, many of them could not read or speak English.

He is the only one in town who could have pulled this off in such a volatile atmosphere of sore racism, solely because he was so visible and respected, and so invisible and inoffensive.

In fact, his standing in the community was so firmly established that following the war he actually ran for office.

Hidden in Plain Sight

So, how was it possible that Isaac Pleasants—a man clearly visible in Mansfield—was able to serve as a Conductor of the Underground Railroad during the most dangerous and watchful years? The answer is simple—it was in the same way he found a niche in Mansfield society: by being a barber.

Runaway fugitives were given only very few guidelines by which to find their way. One of them was, of course, the North Star.

The other was a Barber Pole.

Highly recognizable—even at night—the striped insignia was an easy landmark to watch for in any strange town.

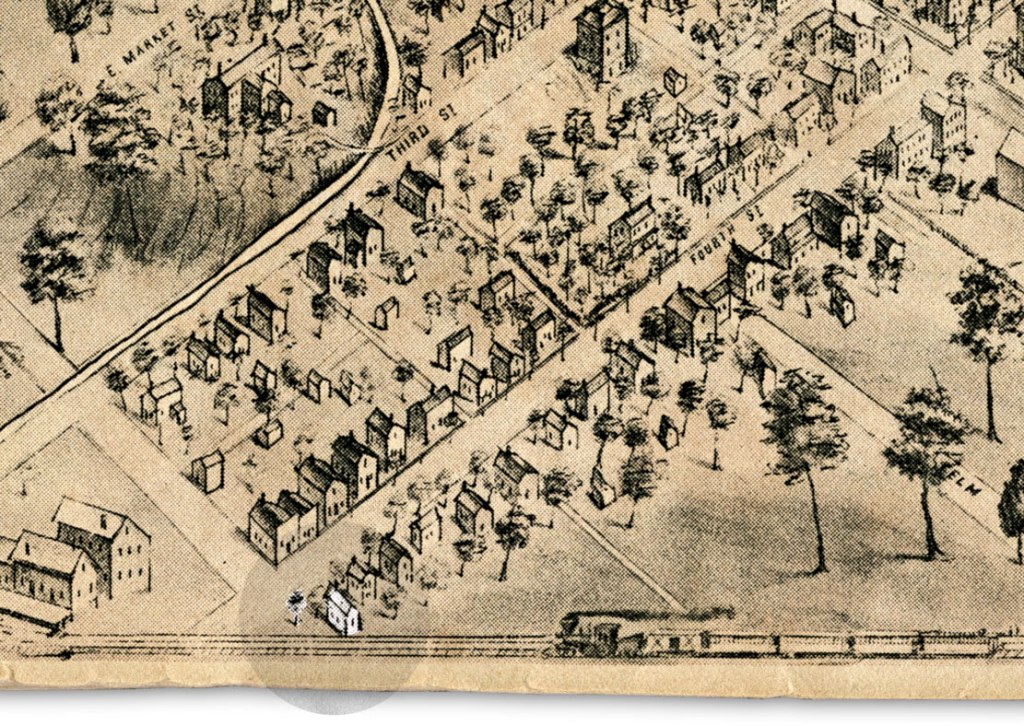

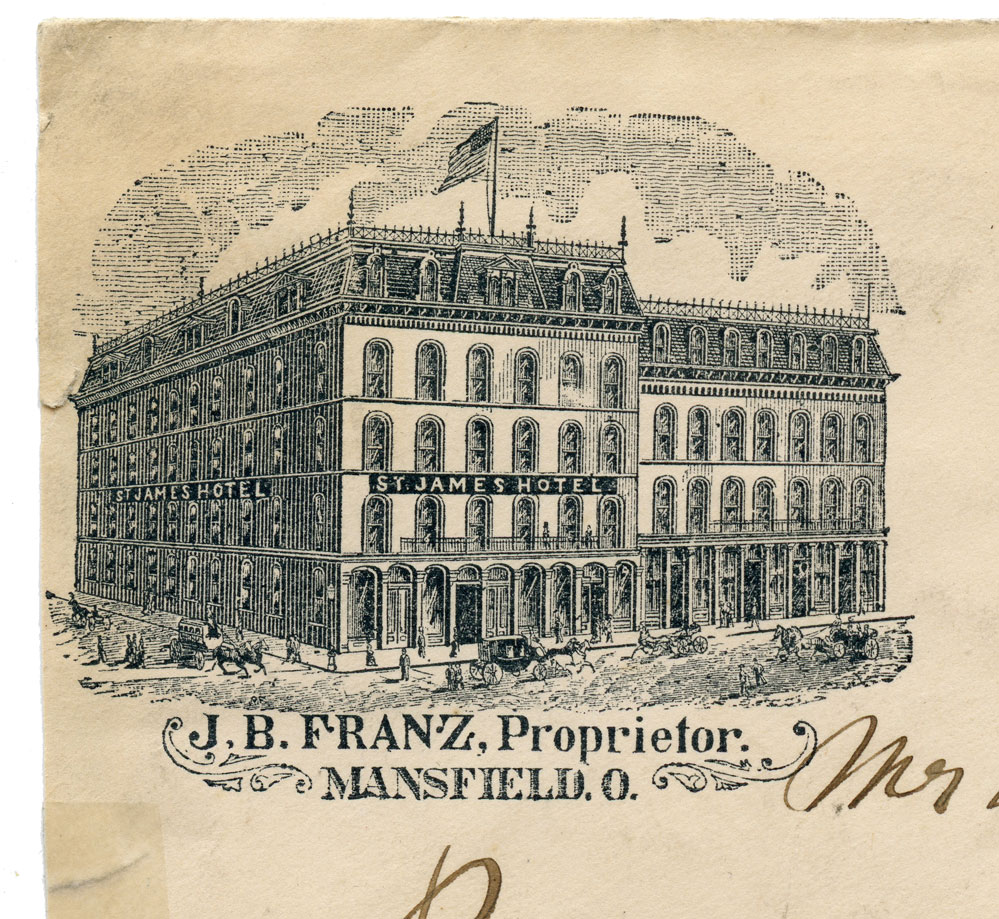

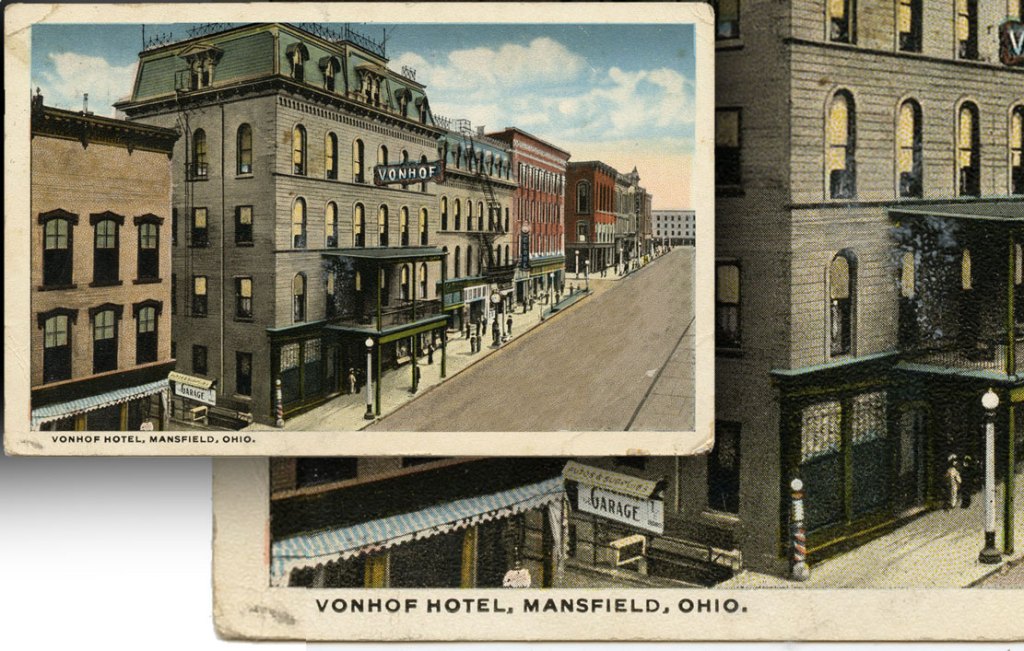

Pleasants had his safe house right next to the tracks, and, though his barbering business was located downtown at the St. James Hotel, he proudly advertised his trade at home by painting those barber stripes on the front and rear of his house where they were easily spotted as an iconic landmark.

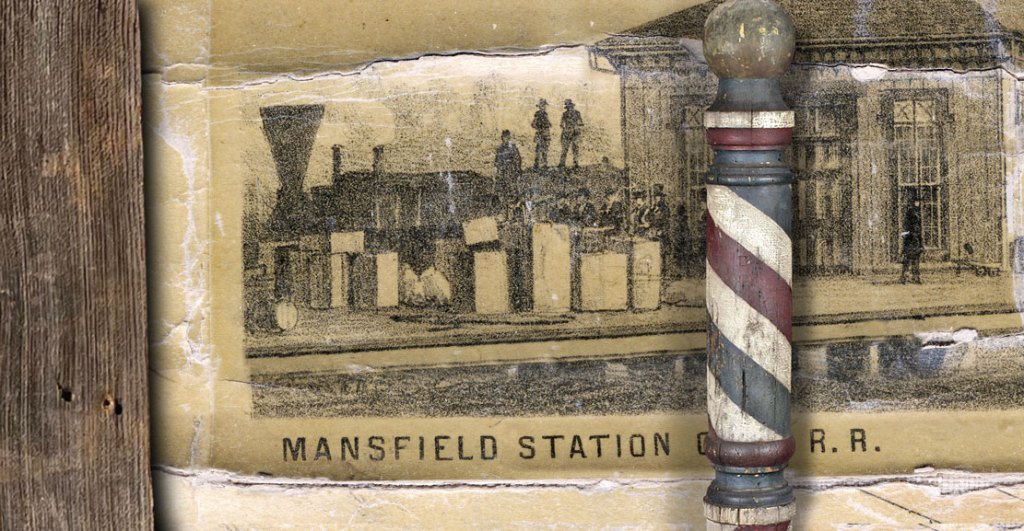

His Station was ideally situated to be completely visible to those searching for it, yet wholly unnoticeable for foot traffic because it was only a few yards from the busy Freight Depot of the Pittsburgh and Chicago Railroad.

Runaway fugitives needed only to follow the tracks on the east side of town until they reached the Railroad Station of the P&CRR, and then look for the Barber Stripes to locate their Station of the Underground Railroad.

There is a certain kind of poetry to it. And the story gets only more poetically interesting the more you know.

Fugitives could find Isaac’s home and he could keep them safe as long as it took to make the next connection. Then he would hand them off to another Conductor in Mansfield who had the means to transport them out of town and to the north. That man was Mathias Day.

Mathias Day was another major influence in Mansfield because he happened to own the other newspaper in town, the Mansfield Herald, that spoke against the Shield & Banner. He also owned stock in the Sandusky & Mansfield Railroad, and through that transport was able to arrange passage for fleeing fugitives on late night trains to the Lake Erie port.

There is no question that Isaac Pleasants and Mathias Day were well acquainted with each other. They both went to the same church.

What is really interesting is that the other man in this weird drama also went to the same church. That was John Glessner, owner of the Shield & Banner.

These three Mansfield men—the Racist, the Humanitarian, and the Black Conductor—all went to the same church. It doesn’t get much more poetic than that: they all worshipped the same God and, subsequently, watched their church split in two over slavery in exactly the same way as the American nation.

Despite the media power of opposing propaganda by a Democratic Party-inspired newspaper and a Republican Party-inspired newspaper, in the end the papers represented only a war of patriotic words.

Ultimately, the man whose action truly spoke in the language of freedom and justice for all was Mansfield’s Black Conductor.

More background on Richland’s Underground Railroad:

Legends of the Clear Fork: Sam McCluer and his Cornfield

Underground Railroad 1854: Unscheduled Cargo in Shelby

The Underground Railroad Part 1: Richland County

[…] The Underground Railroad Part 2: Mansfield’s Black Conductor […]

LikeLike