There were three decades of the Twentieth century when the famous novelist and activist Louis Bromfield was a familiar name to readers and movie-goers in America and around the world. This article is not about that man. This story is about young Lewis Brucker Brumfield, a skinny kid in Mansfield who would one day grow up to become that other man.

In many ways, these two guys—the man and the boy—were very similar. They both loved their dogs easily as much as their friends and family. They both had their hands in the dirt as often as possible, planting things and harvesting things.

They were both voracious readers.

But there were significant differences as well. Young Lewis was outgoing, friendly and popular in a way, but he didn’t have a lot of close friends his age. Louis, on the other hand, had so many friends he often found it difficult to find time to be alone with his thoughts in order to write. No small part of his popularity was because he was among the highest paid authors in America, and he was not shy about sharing his good fortune with friends by picking up the tab.

Lewis, on the other hand, grew up on the lowest rung of lower middle class. His father wasn’t poor, exactly, but he put his income into various speculative ventures and no one told him he had no talent for speculation. We can be sure Charley Brumfield had ambition, though, because he named his first son after the prominent judge—Lewis Brucker—who ruled the county’s politics. Charlie was hoping to climb the ladder of influence. Unfortunately, he lost more elections than he won.

It was Lewis’s mother who had the common sense in the family—after a sense. She determined that her children would rise in society through those arts which were not dependent on family money. She intended her daughter to become a famous musician, and to this end mother spent all the months of her pregnancy listening to symphonies. Then she arranged to have a piano moved into the house before the child was even born. Lewis’s sister, Marie, did, indeed become a concert pianist of considerable reputation around New York in the 1920s, as evidence of her mother’s thoughtful influence.

Lewis was similarly coached for a life in the arts. Mother decided he was to become an author, and during his months in the womb she read continually, often aloud, and had the house stocked with shelves of books. The first readings little Lewis cut his teeth on from early age were volumes of Classical Literature from college curricula of Western Humanities.

No doubt this is why his schoolmates were somewhat wary of him. Lewis never seemed much interested in 1900s current events, but he could easily chatter on and on about characters in Dickens and Voltaire and Cervantes.

Type Casting

His favorite book growing up was a novel from 1848 called Vanity Fair by William Thackeray, a story about a poor young orphan woman who moves in with a rich family.

Lost in the world of that very class-conscious drama, it was easy for Lewis to imagine his life in Mansfield exactly like a Victorian Comedy of Manners novel with a similar cast made up of High Society looking down on struggling Middling class relatives, with well-meaning auxiliary town characters, and Abominable class villains.

The struggling Middling class relatives part of this equation was no stretch for Lewis. He described his home on Third Street as a sort of family hotel for down-on-their-luck relatives.

But Lewis’s adventurous old grandfather lived on the couch, and the boy grew up to tales of prospecting across America from the goldfields of California to the tall ships of Boston. The boy’s other elders in the family were just as full of stories as well: of pioneering in frontier Ohio, fighting for justice against Slave holders, and, in other picturesque ways, playing a vital role in the young nation.

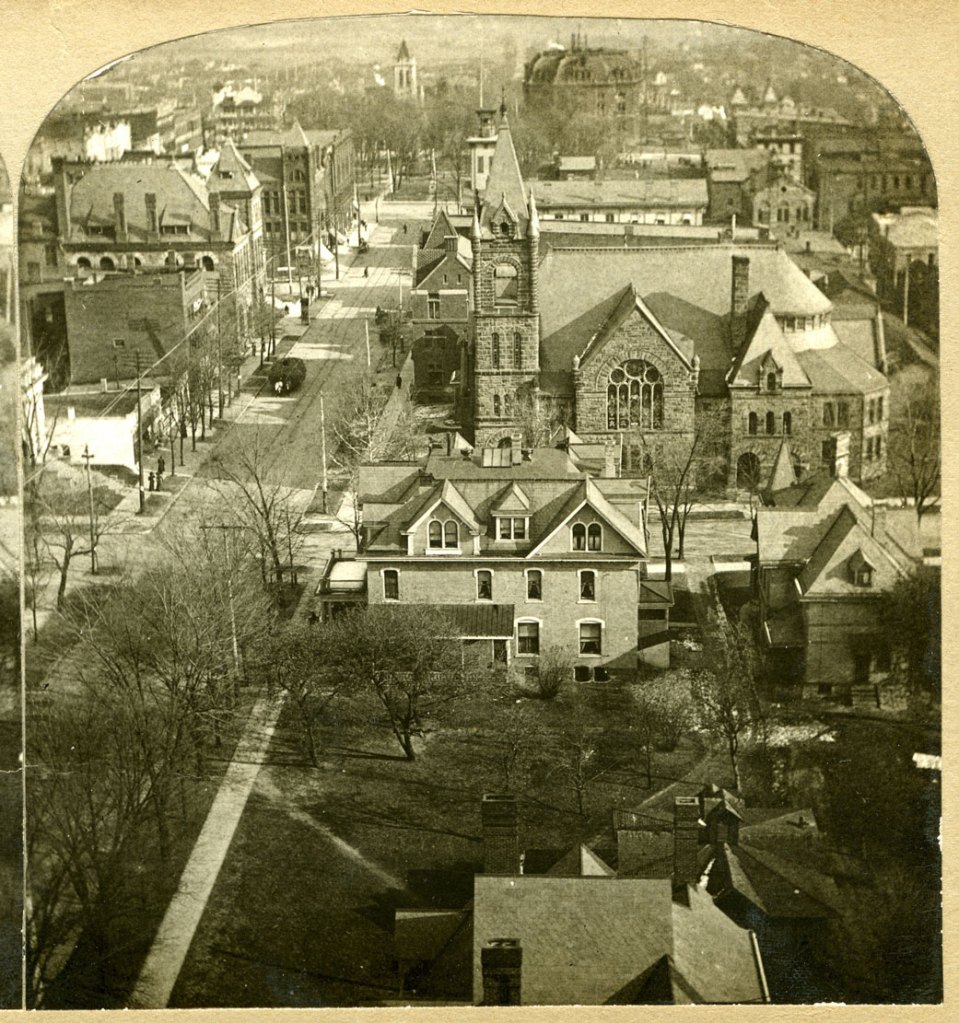

So it was not difficult for the boy in Mansfield to see himself in the mainstream of American history, and to see how that epic tale was embedded into his hometown. Lewis said he used to climb up in the massive steeple of the Congregational Church to peer down on the center of town, and he saw it like a map printed on the endpages of a grand novel of which he was a character and, simultaneously, the author.

Character Types

Looking at the town through the eyes of his Vanity Fair class consciousness, Lewis began absorbing the social landscape of Mansfield as well. Fortunately for his education in character types, he had relatives who were as close to local royalty as the city offered, so he could study the Upper Class up close. This was the Jones family, and their landmark estate—known familiarly around Mansfield as Oak Hill—ultimately served as the high society background in his first novel.

A Type of Farm

Growing up in the Brumfield family afforded Lewis another kind of practical education as well. His father invested a considerable amount of his capital in procuring a sequence of farms that he intended to resell at a profit. He could only afford to buy a certain type of farm—those that were pretty far gone and used up, with ramshackle barns and fields full of weeds.

Consequently, young Lewis invested a considerable amount of his youth fixing fences, mowing weeds with a scythe, and shoveling out old barns. It was hard work and long hours, and what it planted in the boy’s imagination was a kind of tireless hope .

So when he was old enough that one of these properties was given to his own efforts to farm himself, Lewis threw himself into the dirt with all the tireless enthusiasm of a teenage optimist.

That’s why his classmate Pauline told me what she remembered most about Brumfield at Mansfield High School was tracking him down the hallways by the muddy footprints he left behind him.

A Typical Politician

There was also one other aspect of Bromfield’s father’s life that eventually came to shape the thinking Lewis valued: it was the man’s commitment to his friends—particularly his friends running for office.

Charley was a diehard campaigner, and in those horse-drawn days that meant hitching up the buggy and canvassing the countryside to gather votes. Lewis went along on those country journeys with his father.

We can assume that through these trips he learned what real farmers thought of politicians and what they wanted from Government. And we can suppose he came to understand the importance of selfless civic service to his community.

But what he spoke of in later life of these jaunts with his father was something else entirely. The journeys taught him the value of Time.

Speaking in the 1940s, Louis Bromfield told a radio interviewer that the advent of automotive transportation brought a tremendous amount of freedom and utility to modern society, but it had destroyed a priceless commodity that future Americans would never know was missing: the luxury of slow horses. In his youth, it took hours to get where you were going behind a horse, and these were hours you had to think about things. They were valuable hours to thoroughly hash out ideas with others. Traveling by horse gave you time to really get to know your family, your friends, and, most of all, your own mind.

“I could not have been more than seven or eight years old. My father, a Democrat and somewhat of a politician in his small way, used at election time to drive out over the county visiting farm and village people, seeking the assurance of their votes, either for himself or for some fellow Democrat. He rode in an old-fashioned buggy, and very often he would take me with him for company. For a small boy, it was always an exciting adventure. We visited nearly every farm in every township, driving up remote narrow lanes that led from the rich valley farms into the hills.”

Up Ferguson Way, 1943.

News Print

As a young teenager, Lewis made his first tentative steps towards a life in words by becoming a newsboy. He not only delivered the paper and sold it downtown, but, without question, he read every issue cover to cover.

Even as a kid he had an acute sense of drama and suspense because he clipped stories out of the Mansfield News and the Richland Shield & Banner to paste in a scrapbook. As a young teenager, he already had words and plots on pages bound between covers as a strange compendium of murders, scandals, and mysteries.

He said he had to hide his murder book from his mother, who was increasingly horrified at his fascination with crime and sex.

(In the 1940s, at the end of her life, after her son had made hundreds of thousands of dollars writing about crime and sex, she was still highly incensed.)

Seeing Himself In Type

The budding relationship between Lewis and the American Language began its early flowering during the years he attended Mansfield High School. His English teacher tried to get him on the staff of their school paper, but by then—at age 17—Lewis already had bigger ideas. He went to work for the Mansfield News as a cub reporter.

Life in Mansfield had, by that time in his development as a novelist, provided him opportunity to explore Mansfield’s characterizations of Upper Class and Middle Class, but now his reporter status granted credentials to walk into saloons in the Flats for a look at the seedier aspects of his town. His editor wrote decades later that he hired Lewis thinking the young man could cover the Agricultural news, county fair, and maybe some church news, but the boy came back with stories of tragedy, scandals and gossip he heard in the bars—crimes so far underground they didn’t even make it to the Police records.

“I asked for newsy tidbits and he brought me Dime Novel Horror Stories.”

MHS Class of 1914

It was during his senior year when Lewis decided his name lacked the gravitas required to be placed on the shelf next to the great authors he wanted to keep company with. So he changed his name and altered the trajectory of his destiny in the American arts.

At age 18 he ended his childhood and became Louis.

What We May Conclude:

From the scope of Louis’ Mansfield youth, it is easy to see the groundwork laid in his imagination for these novels and stories:

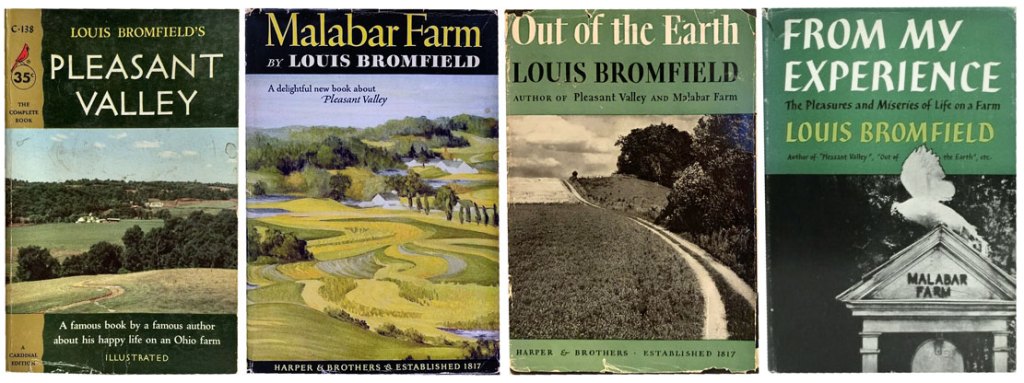

From Louis’ long excursions through the hills with his father campaigning on Richland roads, it is easy to see the fascination engendered in his conscience that led eventually to these books:

And from Louis’ years growing strong by working Richland County farms, it is easy to see the passion for soil seeded into his soul in these books:

True to Type:

Post Script:

The summer when I first went to work at Malabar Farm, I decided to read all the Bromfield books I had skipped over, and found there was only one left: A Modern Hero. So I found a copy and took it on my bike to my favorite reading spot at the old Sandstone Quarry north of town where I could sit in the shade all afternoon high above it all with only distant sounds of the city.

I was never interested in that particular book—even though they considered it good enough in 1934 to make a movie of it—because it wasn’t one of the novels with a Mansfield background. But as I got into the chapters that day at the Quarry it became increasingly obvious that the story was, indeed, written through Bromfield’s Mansfield experience as a kid, and it was clearly set in our town with easily identifiable local settings.

In fact, there is a scene that takes place at the Quarry!

So I watched the movie and within the first five minutes they’re sitting in the Quarry!

As I read his words at the Quarry in 1993, I was transporting to Bromfield’s thoughts in France in 1932 as he remembered back to the Quarry in 1912. Inside the Mansfield Earth inside the Mansfield kid’s mind. Mining the past with words.