The landmark in Mansfield best known around the nation and the world, as probably the principal reason our town is on the map, is the Ohio State Reformatory.

OSR has significant historic cache in modern popular culture because of its iconic familiarity in the background of the 1994 classic film, The Shawshank Redemption. Enthusiasm generated by that film alone keeps the site current in public imagination, enough to draw 100,000 tourists a year.

But even more immediately relevant in attracting crowds to the site is the annual phenomenon known as Inkcarceration, a music and tattoo festival that brings 75,000 concert fans in just one weekend every summer.

There is no denying the cultural relevance of OSR during that weekend of July, when the prison becomes the epicenter of a staggering amount of traffic. And an absolutely stunning level of volume from screaming guitars of 63 raging bands.

The noise is astonishing. It’s a sensory onslaught. It is the angry kind of volume that stings your cheeks like a blast furnace and threatens to crush your skull.

Understood in the correct context, the roar is insanely relevant.

A prison may seem a rather randomly ambiguous venue for such high-intensity attention, but this particular prison was intended from its very inception to be a destination to arouse stirring emotion.

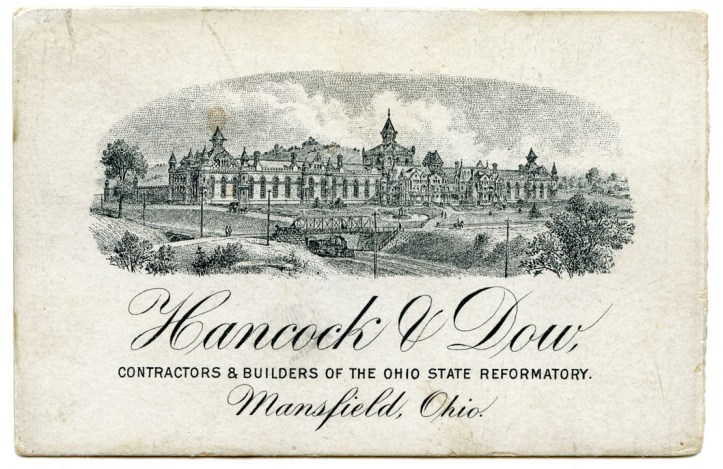

The architect who designed the Reformatory in the 1880s believed that architecture based in classical high culture could literally lift the spirits and aspirations of lost young men.

The design of the prison walls was, accordingly, appropriated from a landmark castle in France said to have been conceived by no less a genius than Leonardo da Vinci. Set on the heights overlooking the growing city of Mansfield, the walls’ awesome grandeur was meant to give inmates a sense of what civilization could rise to.

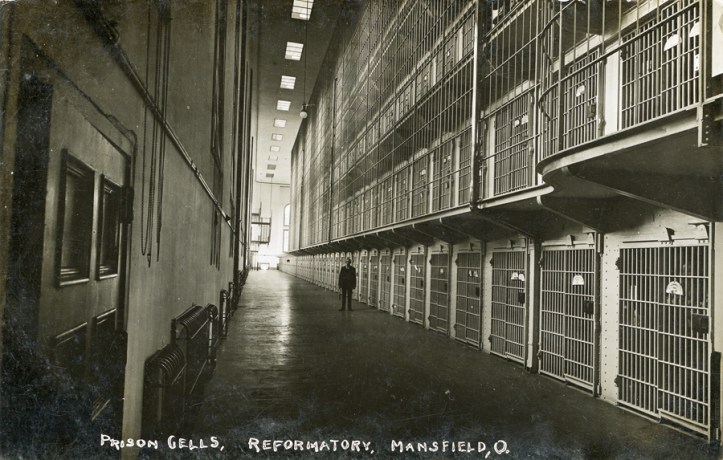

That was the idea, anyway. Ultimately, however, prison is prison and inmates are prisoners.

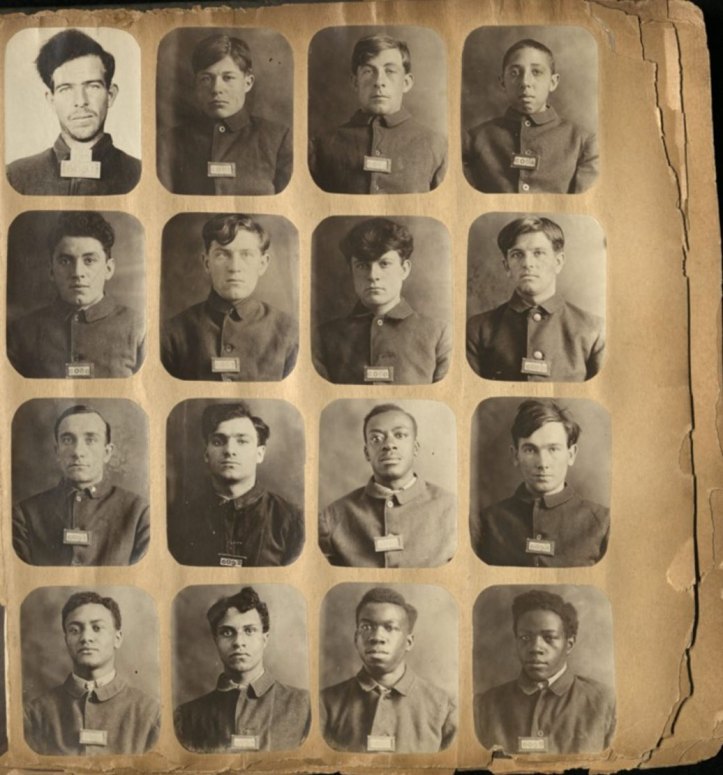

OSR was created specifically for young convicts, who were given their own facility so that they wouldn’t get ideas from older, hardened criminals. The institution held men as young as 16 years old. “Colts,” was the term those 19th century wardens used, euphemistically, of their prisoners, implying innocence and rambunctious enthusiasm.

But no one locks colts in the barn. They run and frisk and charge through the fields. No less was the imperative of wild young males in the throes of full early adult vigor.

The explosive passion of barely contained male aggression, when trapped in a human body, and then locked in a cage, is like taking a thousand amps of raw power and tamping it down to a single light bulb, and then trying to keep the light dimmed.

A young man caged is a human dynamo for generating frustration, at the high end of the spectrum, and other distempers on down the scale from anxiety and anguish, to grief and terror.

That is the output from one prisoner. Multiply that from 1896 to 1990 by thousands and thousands of young men, and OSR was an incomparable power plant manufacturing twisted energy on an unparalleled scale.

One thing we know about energy of any kind is that it cannot be destroyed—all of those gazillion kilowatts of pain, anguish, horror—it still exists.

So where did it go?

No doubt a lot of it went into those stone walls built to contain it; as clearly evidenced by OSR’s reputation for paranormal activities.

That accounts for some of it, but undoubtedly it went into the ground as well, a radioactive contamination clear down to the bedrock of the planet.

It went into the etheric atmosphere. There was such an overwhelming volume it seeped between the layers of reality where it is stored in Time.

That energy is still there underneath the surface of reality. The terrible tectonic pressure of imbalance is stored at those coordinates on the globe just north of Route 30.

And every summer we take the opportunity to open the valve, just a little, to ease the pressure and let some of that screaming angst out.

That is the roar you hear driving past Inkcarceration.

NOTES:

It was Scofield’s conviction that inmates of this Intermediate Penitentiary could have their aspirations lifted to a higher spiritual plane by living in sublime surroundings that were charged with culture, refinement and ancient tradition. To this end, his design was based on a historic 16th Century castle in France—the Chateau de Chambord—whose turrets and spires are said to have come from the drawing board of Leonardo da Vinci.

The OSR plan is known to be a compilation of architectural elements from several different castles and palaces, but it is easy to see that with a little stretching, cutting, cloning and unfolding like a Transformer, it wouldn’t take all that much imagination to turn the French Chambord into the Mansfield Reformatory.

One of the newspaper editors, who was also a convict alumnus paroled in 1947, became the published author of a popular prison novel written inside OSR: Four Steps to the Wall by Jon Edgar Webb.

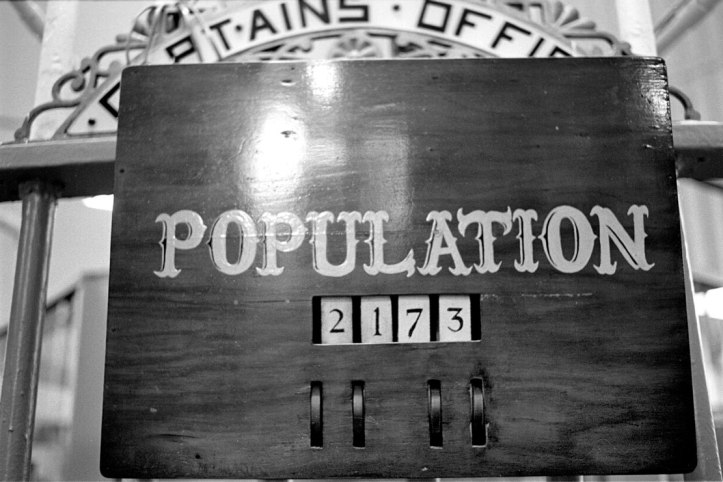

Calculating the actual number of inmates through the decades is not easy because a large number were paroled every three months and replaced; and OSR often received overflow prisoners from other Ohio facilities. During the 1950s, the prison regularly housed 2,500 prisoners, with as many as 3,600 at one time.

In 1973, a State investigation suggested that a total of 86,021 young men had been housed there by then.

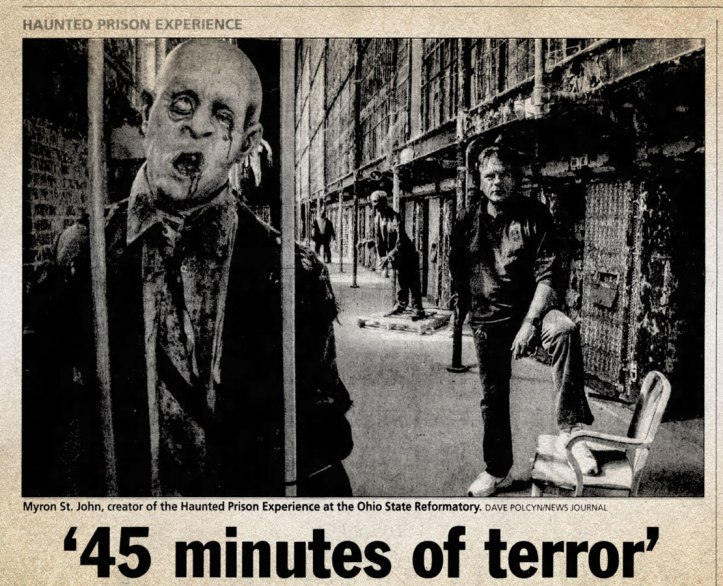

OSR in American Popular Culture

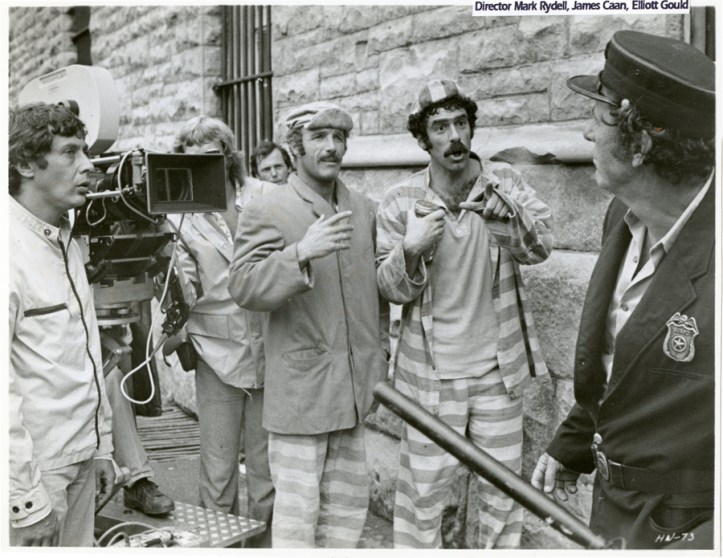

Hollywood discovered OSR as a photogenic prison movie set in 1975 when Columbia Pictures filmed Harry and Walter Go to New York on site while there were still inmates in residence. James Caan and Eliot Gould imbued the landmark with its first credible star power credits.

Filming continued much of the summer and the positive attention it brought made rescuing the old prison seem not only possible, but a good business prospect. In 1995 the Mansfield Reformatory Preservation Society wrangled a stay of execution, and acquired the landmark for its next life.

OSR Here and Hereafter

The Monster Crowds

Those 1890s young men could probably not fathom the musical aspect of the festival, but would no doubt line up for the tattoos.

Thank You

Images and information in this article come from many sources including the Mark Hertzler Collection, Former News Journal photographer Jeff Sprang, John Stark, Richland County Chapter Ohio Genealogical Society, Phil Stoodt, and the Sherman Room Mansfield/Richland County Public Library.