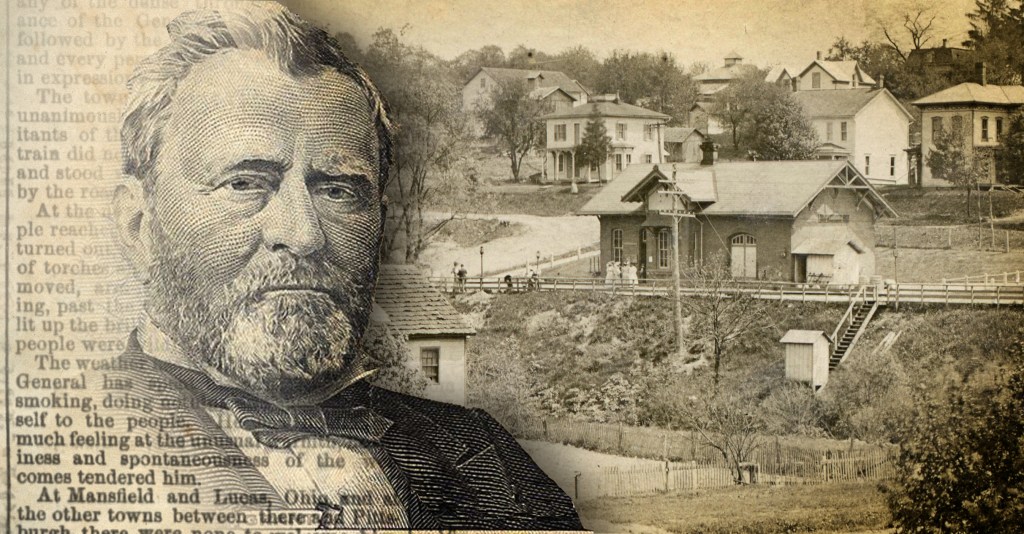

Richland County has always been a significant crossroads in middle America where major railroad lines cross, which has created opportunity for so many historic encounters that most of them are completely unrecognized.

Imagine how many interesting characters came through Richland County on the way from New York to Chicago in the many decades before there were highways or airports; when the only transportation available other than trains were steamboats or horses.

Imagine how many fascinating and history-making figures stepped off the train to buy a paper while the engineer had paused for ten minutes to take on water. Those footprints are here in the dust of Richland County in a way that binds us to powerful eras of passing history.

One of the really fun aspects of researching local history is stumbling across documentation from the great age of passenger trains that places notable individuals from our American past into the picture frame of our home.

It changes the way you see those tracks; it invests a spirit of importance into empty village lots where once there stood a depot. It certainly changed the way I looked at the site where the Lucas station of the Pennsylvania Railroad stood: after I read about the night Ulysses S. Grant stepped off the train in Lucas.

Election Year

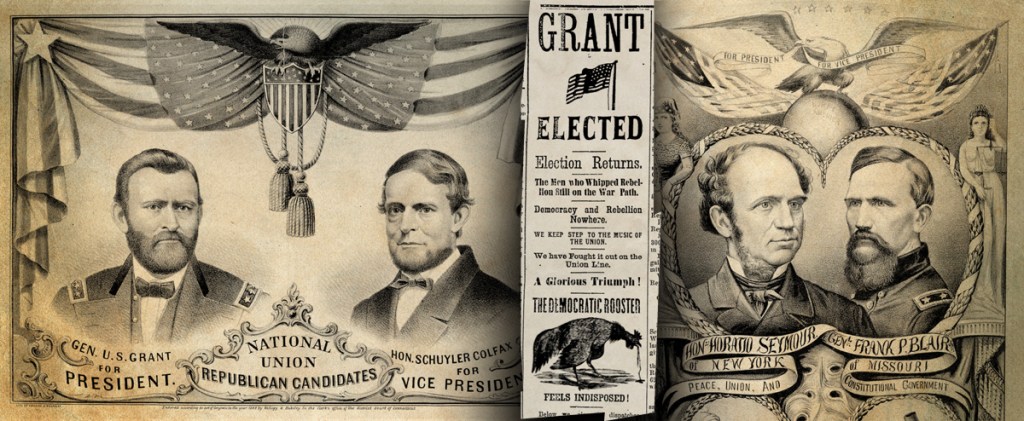

It happened in 1868, and election Tuesday fell on November 3 that year. It was the first Presidential election since Lincoln was felled and smoke had cleared from the Civil War.

It was a bitter and hard-fought campaign, not unlike the war itself, with hard feelings on every side. On Wednesday, November 4, all the newspapers announced that the man moving into the White House would be General Ulysses S. Grant.

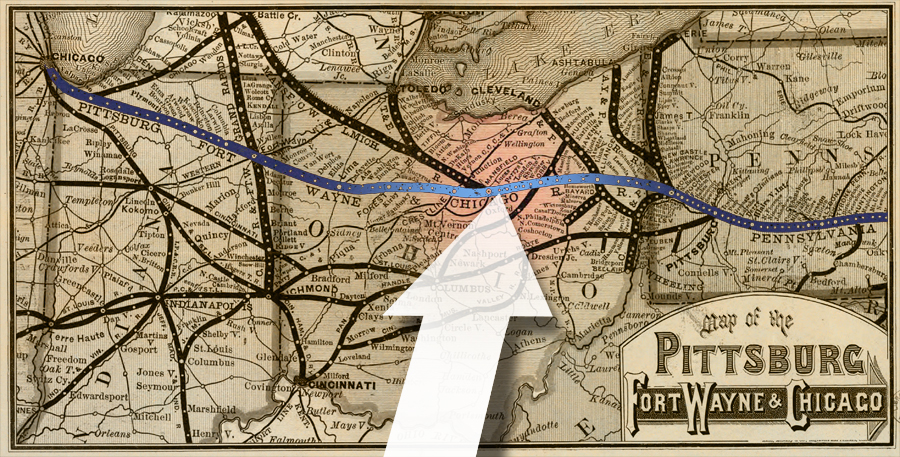

Then on Friday, November 6, Grant stepped aboard a train in Chicago and headed for Washington DC. The President-elect had advisors who thought it best if he avoided big cites on the way, like Cleveland, Columbus or Cincinnati, where huge Republican crowds might provide cover for little Democratic assassins.

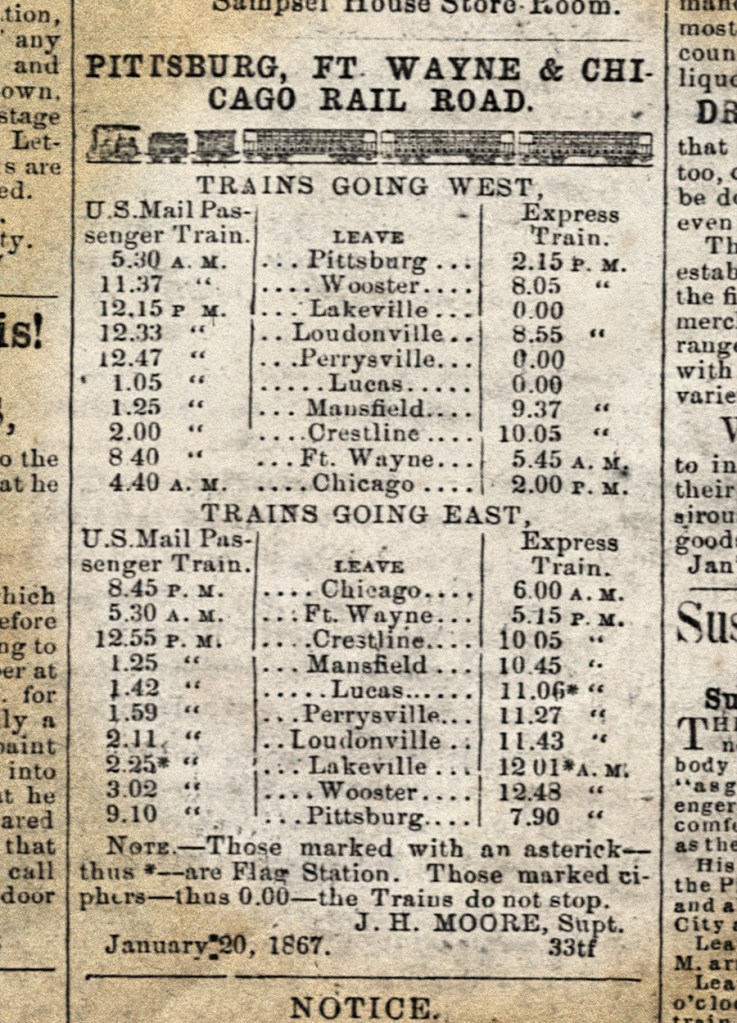

So the tracks that Grant rode across Ohio that night belonged to the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne and Chicago Railroad; which passed through Lima, Bucyrus, Crestline, Mansfield and Lucas.

Underway

General Grant was a giant among American celebrities in the post-war years, but he was not a large man, and he was inordinately modest for someone about to stand at the head of all those loud Capitol politicians. When presented with the opportunity to receive the accolades of thousands of adoring fans during his victory lap across the U.S., Grant demurred, and agreed only to speak to groups of his Union Army veterans.

Those huge roaring crowds embarrassed him. Not that he wasn’t grateful for their support: when the train arrived in Fort Wayne and there were 1,000 working men lining the tracks cheering, he stepped out on the back of the caboose and shook hands until the train pulled away.

When he reached Van Wert, the old Army Artillery unit fired off thunderous volleys in salute as he passed.

By the time he hit Lima, the entire town was packed on both sides of the tracks, so the train had to slow to a crawl just to get through without running anybody over.

And from that point eastward for the next hundred miles, there was not a crossroads or hillside farm without folks waving their hats and carrying torches.

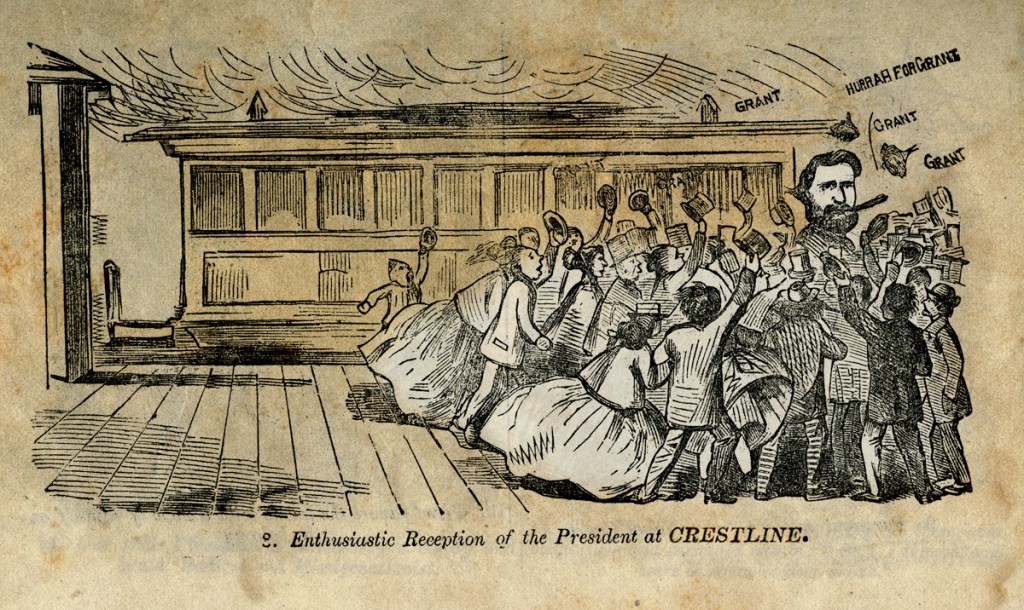

By the time the train got to Crestline around 10 PM Friday night, the Ohio party had escalated to a full-blown spectacle with brass bands, people singing by the light of a hundred torches; as “blazing bonfires lit up the brilliant scene, and thousands of people were wildly rejoicing.”

Grant stepped out onto the platform to pat some children on the head, and was inundated with a mob of fans all trying to touch his coat, his whiskers, his hat.

10:45 PM

Rolling across the western townships of Richland County, the president-elect’s entourage had a few minutes to dust off their hats and prepare for the next act of the festivities. The fever pitch of euphoria and mirth had only escalated the farther east they came; and none could imagine what overwhelming ovation might be up next.

When the locomotive steamed into Union Station in Mansfield however, the loading platform had only a small cluster of ticketed passengers waiting to step on board. There was a big dog sleeping by the luggage trolley. That was it.

Everyone in the train cars was staring out the windows like there might be a surprise party just behind the building, waiting to spring the trap. “Is there more than one depot in this town?” they asked. Maybe the crowd was mistakenly gathered over at the B&O.

The one person on board who was not perplexed or dismayed was General Grant. For him, it was a relief.

11:06 PM

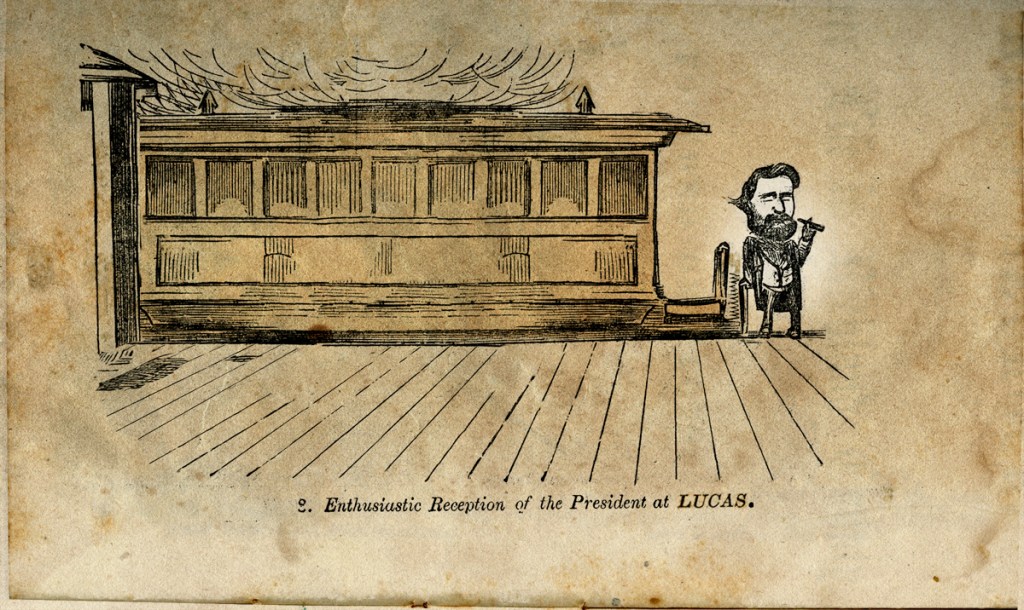

The next station, the one at Lucas, was what is known as a “flag stop,” which meant the train came to a stop only if there was a flag posted by the tracks to indicate passengers or freight getting on board. At a little after 11 PM there was a lantern up the flag pole, so the General’s transport came to a halt.

There was only one man standing there. He had a horse he was loading into a boxcar for the short ride to Wooster.

The train paused for a few minutes, and the chuffing of the steam sounded like the train was perhaps catching its breath after all the excitement.

Only one person got off the train in Lucas: it was Ulysses S. Grant. He was pleased to have a couple quiet minutes in the night, alone with his cigar.

The newspapers and the history books tried to gloss over the whole Richland miscue by saying that the telegraph operators in western Ohio neglected to notify Mansfield or Lucas that the hero was coming. Perhaps that was true, but there is another unavoidable fact to consider as well: quite simply, Richland County did not vote for Ulysses S. Grant. They voted for his Democratic opponent 3,754 to 3,300; and the Monroe Township vote was even slimmer for the next President.

In fact, the Village of Lucas was so stridently supportive of the other candidate, that once the election was over and Grant was elected, the Mansfield Herald facetiously claimed that the reason no one was at the depot in Lucas was because the community leaders had all left town: on a journey sailing “Up Salt River.” (This is a common 19th century joke, most easily understood as, “cry me a river of salt tears.”)

Historic Site

The tracks through Lucas came to be known in the next century as the Pennsylvania Railroad, and the classic little depot was sited at the end of South Union Street, where Moffett Road begins. The building has been gone since the 1940s, so I never saw it except in old postcards, yet even so, there is a kind of sweet nostalgia about the site that I have enjoyed ever since I first read about the famous train of 1868.

I can see the place in my mind’s eye whenever I drive over those tracks, particularly at night, and I always have a clear picture in my imagination: it is Ulysses S. Grant standing alone in the lantern glow under a little cloud of cigar smoke. He’s listening to the tumbling Rocky Fork echoing through the valley and gazing up at the stars caught in the treetops, and murmuring to himself, “Thank God for the quiet in Lucas.”

[…] Grant’s story in Richland County: […]

LikeLike