When I knew her in the 1970s, Pauline was wiry as a tiny bird, and seemed to sort of fold into herself when she sat down, with her knees and her sharp little face all that emerged from the sofa; but she told me that when she was 40—in 1943—she was plump as a Thanksgiving turkey. Those were her words.

She told me her story in soft phrases that I cannot hope to recapture today, but I hope this pale shadow of the powerful tale she cast into my memory will do honor to her splendid spirit.

That evening I noticed there was a small star she had pinned to her collar; I didn’t recognize it: the thin gold star had a wreath around it like it might be the emblem of a service club organization. I asked what it stood for.

That’s when she told me about the year she became a Gold Star Mother.

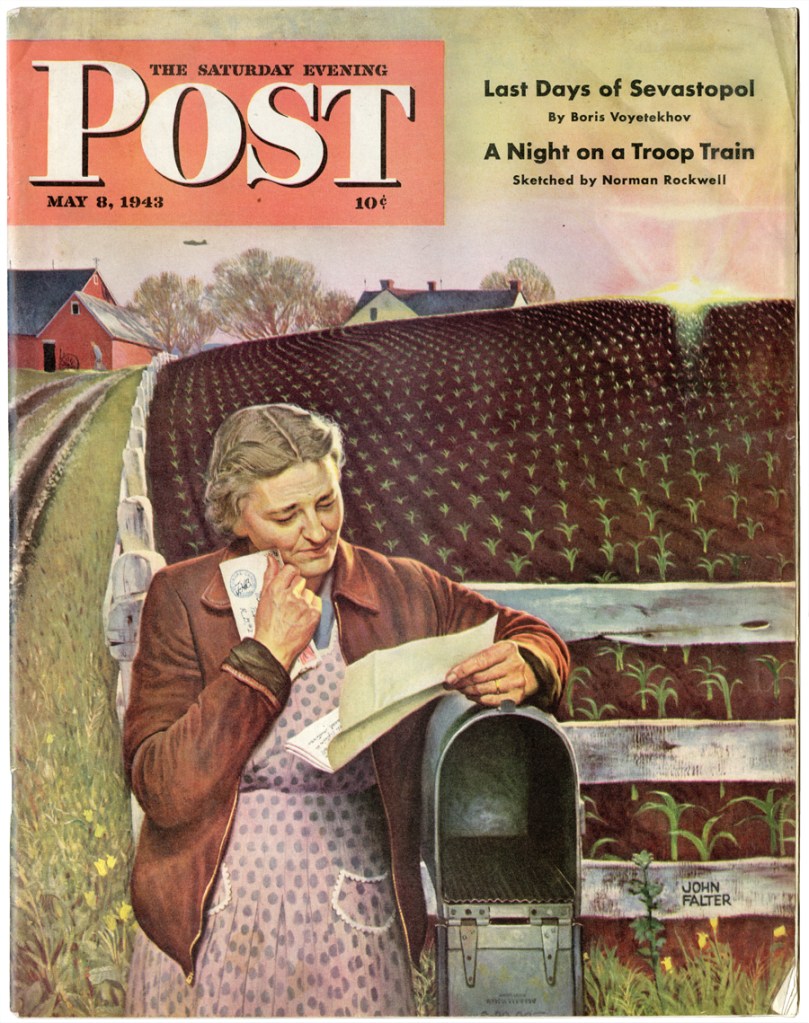

1943: WWII

When her son Willie enlisted, he had only just turned 18; and as soon as he left on the train, Pauline dutifully hung the blue star service banner in her front window. It hung there only twelve weeks before he was so soon lost in the war, and she had to take the blue star down. She couldn’t bring herself to replace it with the gold star.

When her Will died she went into a kind of dream state, and she didn’t want to wake up because going into Lucas to shop or to church meant she had to face her friends; and it hurt too much to admit she was awake and all of it was real.

Her friends recognized that she was drifting away, and they did everything they could to keep her anchored to earth by keeping her involved. She went along with their ministrations and plans listlessly, like a big puppet, and that was how she found herself in the Richland County Red Cross as a drafted volunteer.

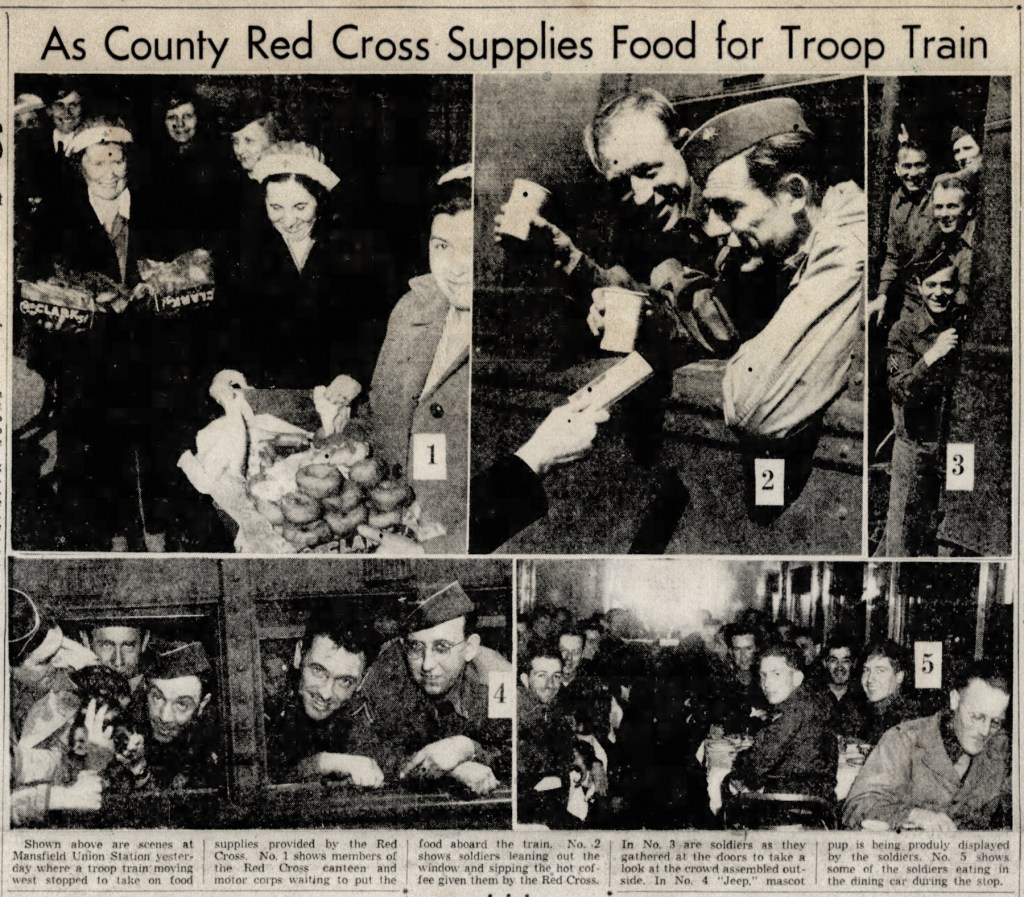

That is how she happened to be in Mansfield on March 17, frying doughnuts when the troop train came in. There was no regular military canteen service at Union Station, but the Red Cross had a mobile food van for emergencies, and this was a sudden and urgent plea. Soldiers traveling west from Fort Monmouth NJ had not eaten since dinner yesterday, and there was no food on the train.

The SOS came in 45 minutes before the train was to arrive, and the ladies in Mansfield dropped everything and scrambled to gather sandwiches and coffee for 150 men.

It was remarkable to watch the city mobilize in selfless action at an instant’s notice, with everybody in top form pitching in to help. It all happened so quickly, Pauline found herself transporting doughnuts in bushel baskets; and that’s how she happened to be at Union Station in her apron.

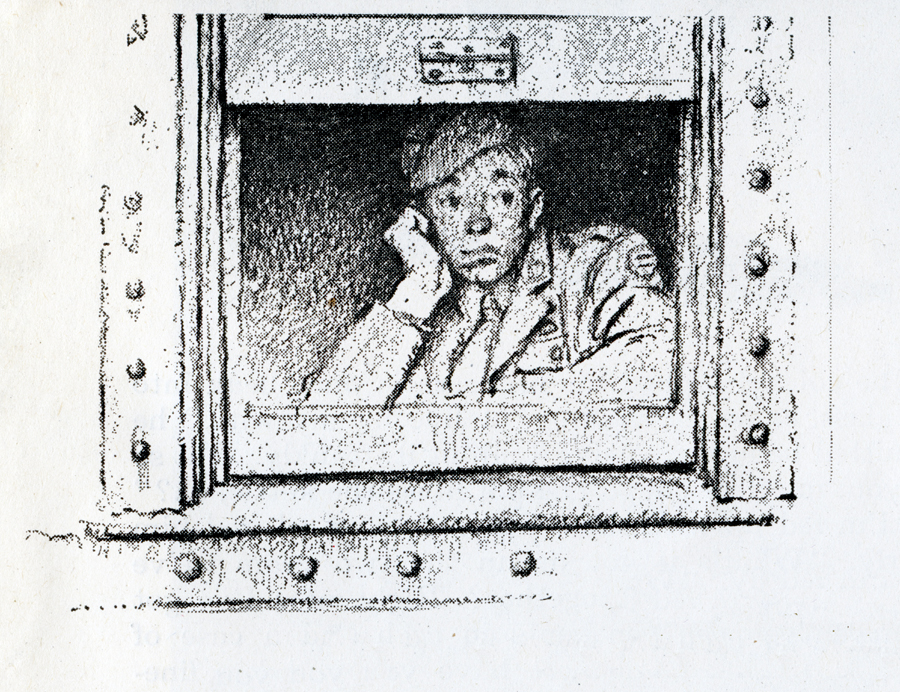

A Window

All she could do was stand and watch the excitement. As she scanned down the train there were four cars of uniformed men, but her eyes were drawn to one particular window. She saw a young man’s face that was so sad, it hurt to look at him.

“My heart just flew out to that boy. His face was so forlorn and hopeless, and I recognized the expression intimately, as if it was my own soul looking back at me from a mirror.”

Pauline walked down the platform toward the despondent young man, and as she drew near his window she lifted her hand to wave at him.

“I couldn’t let him roll away without at least trying to give him a moment of encouragement. All I wanted to do was say, ‘It will be all right.’”

What happened next was way beyond her hopes: the boy caught sight of her and his eyes flew wide, and a brilliant smile split his face. It was as if he recognized her.

The two of them spoke briefly through the raised window, and he told her just exactly that: for an instant, he thought she was his mother. The apron, the smile, the wave…it was just like his own mother reaching across time and space to say hello and good luck!

When the train pulled out, Pauline was transformed.

She may have lost her son, but that didn’t mean she wasn’t a mother. She would be mother to all these young men.

That was how simply her life changed. That was how she came back to earth and woke to her new mission in life.

Every time she heard the train calling in the distance, she dropped whatever she was doing, put on her apron, and ran down to the tracks to wave at all her sons.

A Gesture

Pauline’s farm abutted right on the Pennsylvania RR tracks, and it was only a quick hurry through some trees to come out on a long curve of tracks where she could be seen for a half mile in each direction.

She never failed to catch the attention of somebody in uniform gazing out the window, and she said if it was even one soul who saw her, that was worth it. Sometimes it was the whole train waving back at her.

Pauline never told anyone what she was doing, and the only ones who ever caught her at it were the girls next door. After that, whenever the young sisters were near, they would join her at the edge of the field and wave at the troops.

She asked for a flag from the Red Cross, and she flew it from a post at the corner of her cornfield, to catch more attention from the trains.

This campaign of encouragement gave her so much energy, she even ran down there sometimes at night when there was no blackout being enforced, and stood there with a lantern in one hand, and a handkerchief in the other.

“Maybe everyone on the train was asleep,” she said, “but if there was even one of my boys watching sadly out at the dark, he saw his mother waving at him in the night and lighting his way.”

Pauline told me, “I lost my boy, but there are so many boys out there that need mothers. After all, you can’t have too much love: everyone needs many mothers.

“People spoke as if I did all this to bring hope to those boys—but the truth is, they were the ones helping me: they saved my life. Every time one of those boys smiled, my life came back from the brink.”

Remembrance

Eventually, of course, Pauline’s neighbors learned of the unique service she provided for the Armed Services, and they tried to have her recognized.

At her insistence however, the newspaper reporters were turned away. She welcomed a couple housewives from down the road to join her at the tracks as they could, but beyond that small circle of friends, the story was never told in her lifetime.