Those people who keep a finger on the pulse of the natural landscape outside the confines of our neighborhoods have expressed increasing concern in recent years about certain forces in play which degrade the quality of our Richland woods and meadows. We have been hearing about various forms of pollution for years, but the latest buzzword in naturalist awareness language is: invasives.

These are non-native species—usually plants—that are introduced into our local biome for one reason or another—because it seemed a good idea at the time—but through subsequent seasons left unattended they spread out of control and try to choke out every other native plant we know and love.

As it happens, Richland County has had its own particular and peculiar role to play in the history of a couple of these prominent American invasives and, oddly enough, both of these phenomena were intimately linked with two of Richland’s most well known and nationally revered persons: John Chapman and Louis Bromfield.

The Nature of Invasives

Before we continue into the story it is well to note that not all invasives are unwelcome in Richland’s landscape. A couple invaders that we commonly accept and enjoy are the pair of summer roadside ornaments: Queen Anne’s Lace and Chicory that you might even find on the dinner table in a fancy vase. Two hundred years ago you wouldn’t see these flowering weeds anywhere in Richland County because they were all still in Europe.

Another species that was not here originally that we cherish and value and fight to protect is the honey bee. And, of course, the most prolific and landscape-altering of all the non-native invasive species: Europeans (who we generally refer to as early American pioneers and settlers.)

Johnny Appleseed’s other Botanical Legacy

There weren’t any apple trees in Richland County before John Chapman came here in the early 1800s, but most people agree that introducing the apple into the local Flora network was a commendable work. There was another different plant he spread around as well, however, for which folks generations afterward quietly cursed him. It was called Dog Fennel.

Johnny planted the seeds of Dog Fennel in the barnyards and hedgerows of Mohican Country from about 1810-1830 because he honestly believed its medicinal and curative properties were earnestly needed on the wild frontier.

By the 1850s Dog Fennel was alarmingly out of control, as can be seen from this 1863 notice in the newspaper at Shelby:

By the 1880s & 90s the term Dog Fennel Party was applied to any politician who was worthless and smelled bad. Any little crossroad in America where folks were too lazy to keep the weeds from growing wild in their streets was called a Dog Fennel Town.

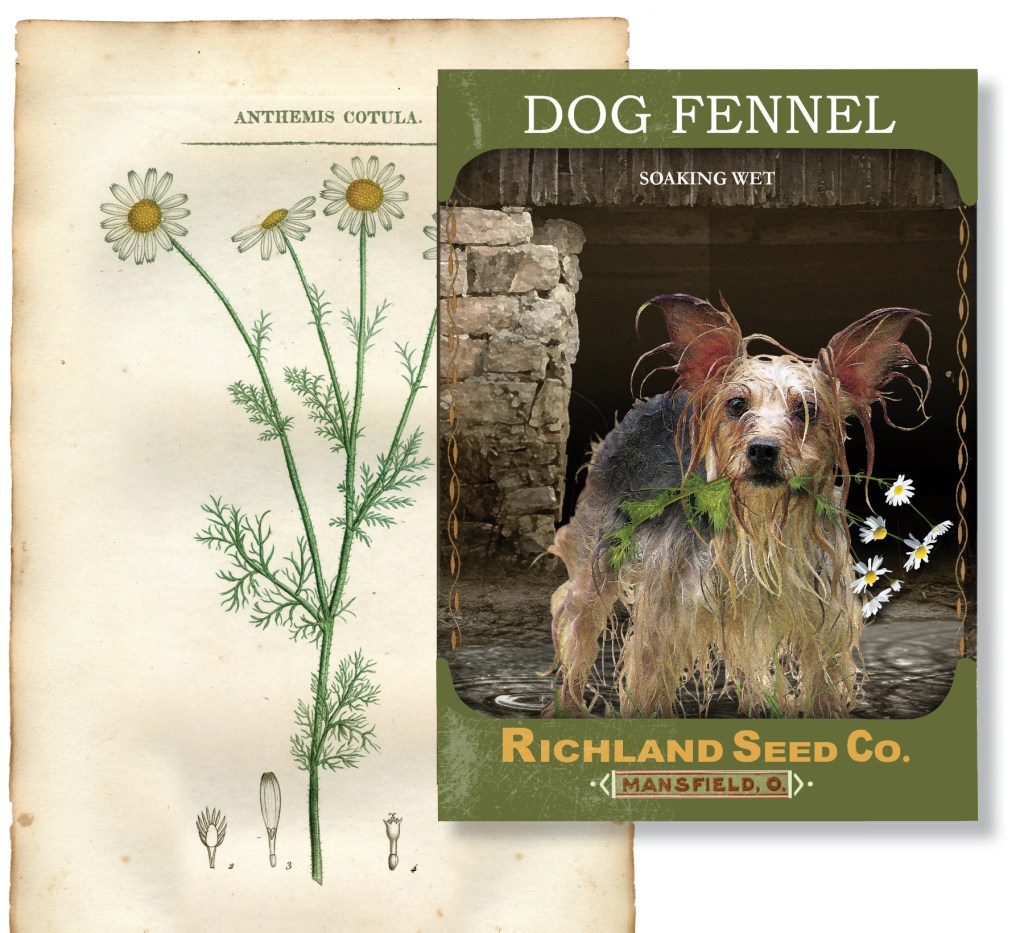

The plant was kinda cute—it looked like a sort of feeble-minded daisy—but it had the unfortunate attribute of smelling like a wet dog. Nightmare stories were told among society entertainers who sent their maid out to gather mint for the iced tea but their maid innocently came back with Dog Fennel and served it to their guests.

Nobody had any fond things to say about Dog Fennel, and for decades after he was gone the responsibility for its noxious invasion of the American Midwest was laid squarely at the feet of John Chapman:

The weed has gone by many other names during the last 200 years in America, among them: Mayweed, Fetid Chamomile, Stinking Dilly and Hog’s Fennel. Chickens won’t go near them, and even fleas and mosquitos are repelled by them.

In 1904 Dr. Wilhelm of Louisville KY announced he finally found a use for Dog Fennel as a cure for consumption. The tonic was made with one sprig of the weed and 90 gallons of whiskey.

In 1889 a scientist in Salem OH discovered an elixir of life using Dog Fennel and gin, he subsequently suffered an overdose and broke his leg chasing his own dog under the hallucination that it was a raccoon.

Another Richland County Epicenter

It would be hard to find a non-native invasive species that farmers in Richland County love to hate more than Multiflora Rose. If there were a time-travel GPS tracking device that could take a progressive satellite image of where Multiflora Rose has spread throughout Ohio in the last 75 years, it would surely show the epicenter of infestation at Malabar Farm in the hands of Louis Bromfield.

He had a prize-winning garden in France—a country where every square foot of ground was carefully tended—and there he discovered the virtues of Multiflora Rose as a gorgeous and useful hedgerow. It kept the cows out, it attracted birds and bees, and it was carefully controlled by farmers who had to make every inch of their small farms count.

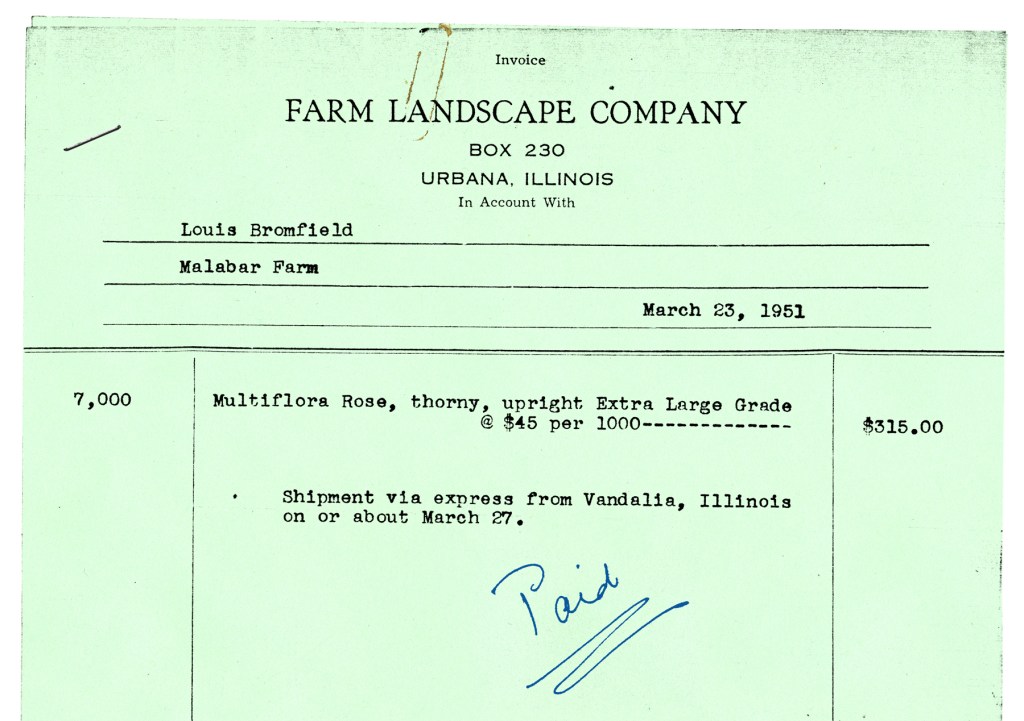

When Louis came back to America in 1939 he was delighted to help the USDA promote their new plan to convince US farmers to plant Multiflora Rose between their fields. He taught by example.

He planted thousands of them. The road leading from Pleasant Valley Road to his home was once lined with the stuff, and it was treated so well it grew in a 500-foot continuous hedge 10-12 feet tall.

Louis died in 1956 and within about 10 years the USDA stopped giving away pamphlets about planting Multiflora Rose, and started printing pamphlets about how to kill it.

I have heard gentlemanly farmers of kind disposition and church-going temperament use the most soul-blistering language when speaking about or to Multiflora Rose.

By the 1970s this USDA publication #374 was practically impossible to find.

The Hope Part of the Story

A hundred and fifty years ago it seemed as if Dog Fennel was taking over the country, with no end of the aggravation in sight. Today the plant is not easy to find in Richland County. The balance of Flora has simply changed through the decades and the despised weed bowed out on its own with no particular encouragement from us.

What happened to it certainly wasn’t men and boys with sickles and scythes: maybe there was something else that came along and crowded them out. We don’t really know, but sometime in the 1920s and 30s farmers just stopped complaining about it because it wasn’t a problem anymore.

Multiflora Rose, on the other hand, has a tenacious foothold in our time. For those who would despair, however, there is hope: it is called the Rose Rosette Disease. It is a plant virus that came to Richland County uninvited, and as a non-native invasive Multiflora Rose-killer it is expected to be welcome as a spring thaw. The little mites who spread it are doing their job quietly even as you read this, slowly freeing our vacant fields from their innumerable rosy thorns.

Rose Rosette Disease (known in the biz as RRD) has the unfortunate side effect of wiping out cherished garden roses as well so farmers need to contain their enthusiasm.

Payback

So many of our non-native invasive species were given to us by the Europeans, so it seems only fitting that in return we let them take home one of our natives. They took one they thought was pretty in the Fall climbing up their gates and trellises, and it went straight to all the finest cultural showplaces and Royal gardens. Not sure what name they gave it…in Latin it’s Toxicodendron Radicans. We call it Poison Ivy.