In 1878 Mansfield had everything going for it: a booming economy based on dynamic industries, a Favorite Son prominent in National politics, an infrastructure growing all the most modern conveniences available, and a state of the art city center reflecting culture and refinement. Mansfield was riding the crest of American civilization.

Yet, in spite of all these dressings of order, stability and civilization, the town bared its teeth one day in May to demonstrate with unquestionable certainty that just under the surface of respectability, the best of people can display their fierce predatory animal pedigree.

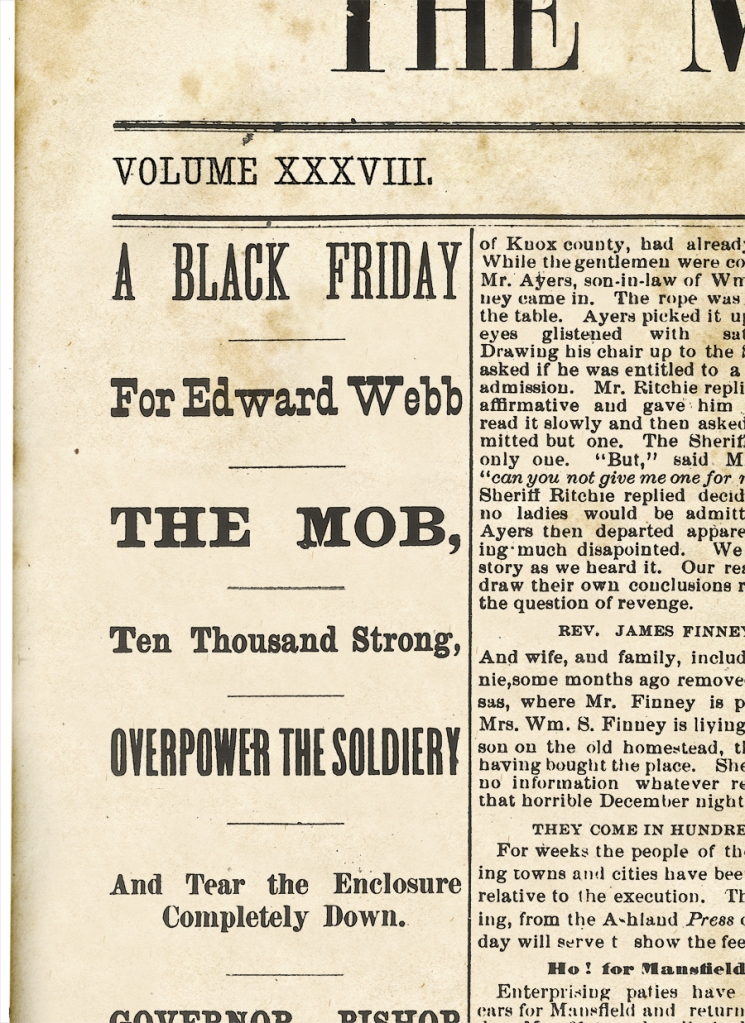

The day was Friday, May 31, 1878 and headlines called it Black Friday. That was the day the County Sheriff scheduled to hang Edward Webb.

The First Crime

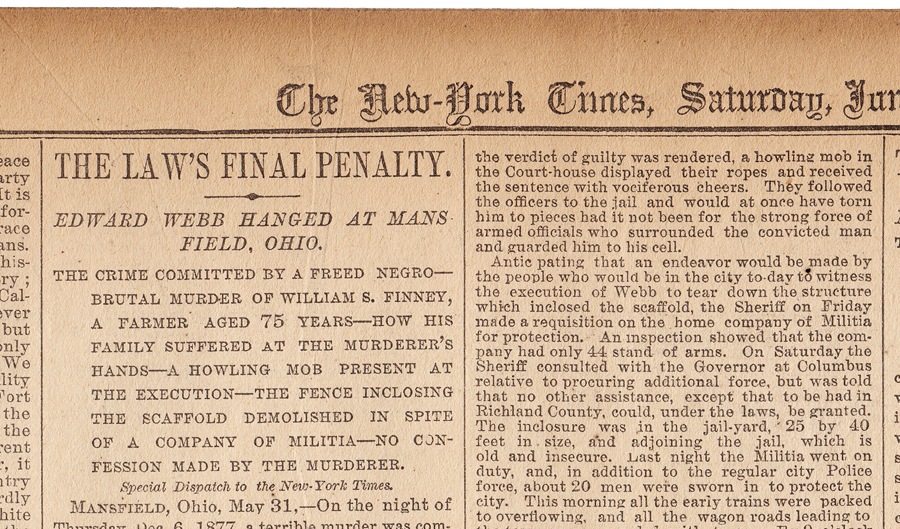

It was definitely a capital crime, and one that stirred all the worst anxieties of the community with headlines in bold-faced type. A robbery gone bad, with a murder, a brutalized family: a white family and a black intruder. It was about as touchy as it could get.

It was the Finney family—an old man and his wife, their son, who was a preacher, and his wife and kids. Their home was isolated, south of town in the middle of what is today Woodland.

The crime took place around midnight on December 7, 1877, and after a surprised burglar and a series of offensive and defensive attacks, the old man William died, and all the adults were bruised and bloody. There were tracks in the snow that led from the Finney home directly to the door on Pine Street (today Glessner Avenue) where Edward Webb lived.

The horror and outrage in Mansfield were palpable, but the trial ensued in an orderly fashion without incident, and the convicted man was sentenced to hang on the last day of May.

The Other Victim

Newspaper writers at the time were restrained in their commentary with no overt racial overtones in their reporting, though there were careful distinctions between ‘prominent citizens,’ (white) whose attentions were directed toward obtaining a confession, and Webb’s ‘colored friends’ who held daily prayer vigils in the jail.

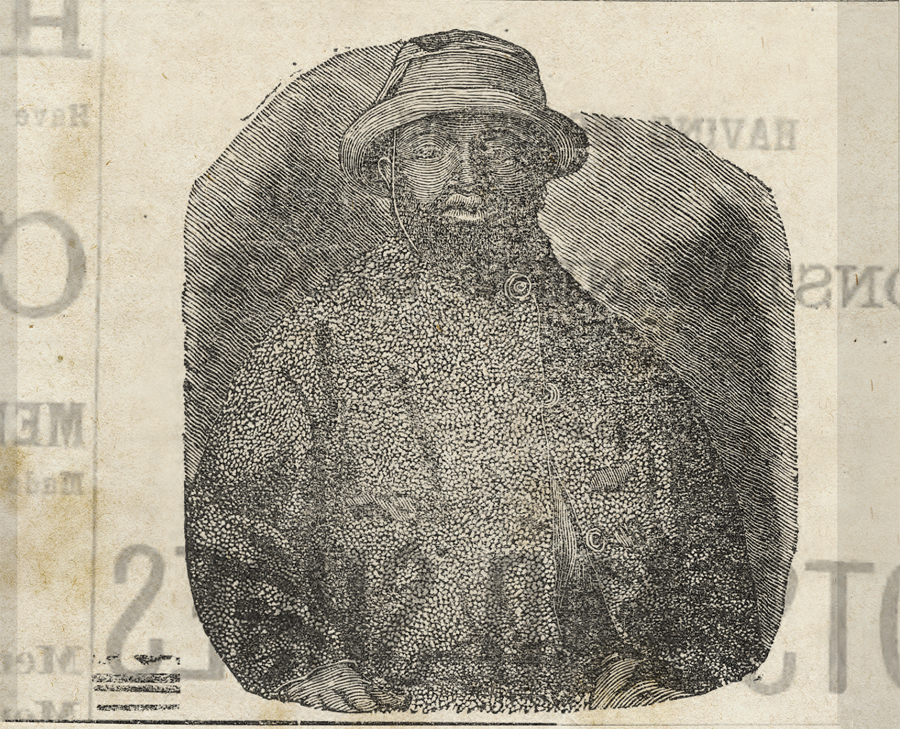

Throughout the entire proceedings Edward Webb himself seemed detached and often amused. In his mid-thirties, Webb had been born in Tennessee and spent most of his life in Alabama as a slave. When disruptions of the Civil War made it possible to escape, he got to Cincinnati and joined the 5th U.S. Colored Regiment for the end of the war.

From that time on there was trouble on his trail all the way to Mansfield, where he made his living as a blacksmith. He denied all of the crimes attributed to him. Webb confessed only that he knew who committed the murder, but wouldn’t say ‘until the right time.’

Pressure Builds

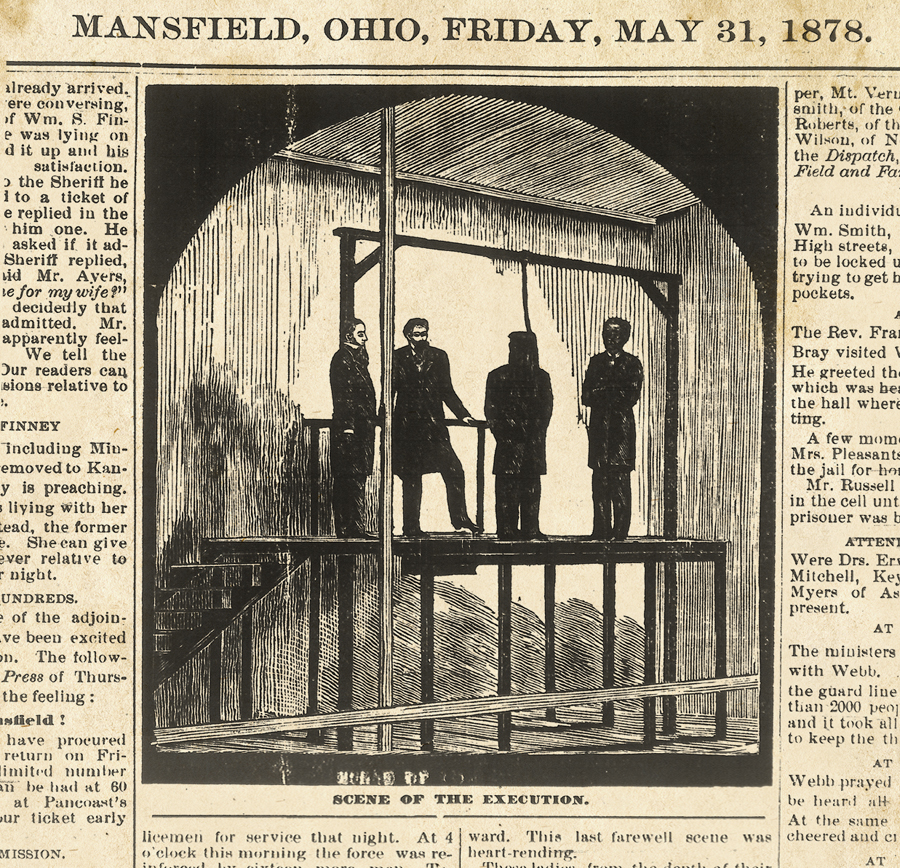

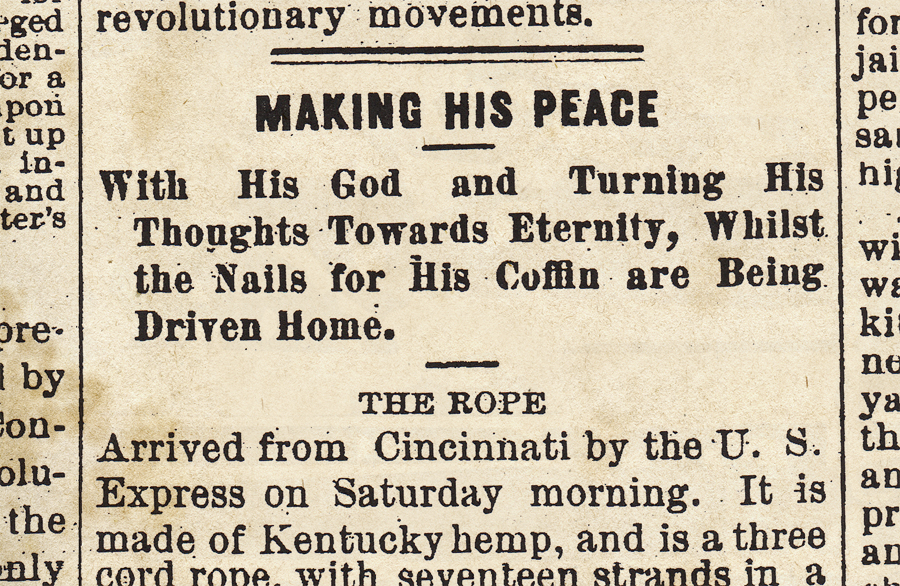

Preparations for the execution of Webb’s sentence were followed in the papers with excruciating diligence as reporters tracked the approach of the scaffolding; researched the rope and where it came from, what it was made of; and enumerated all the strict dictates of Ohio law surrounding a proper hanging.

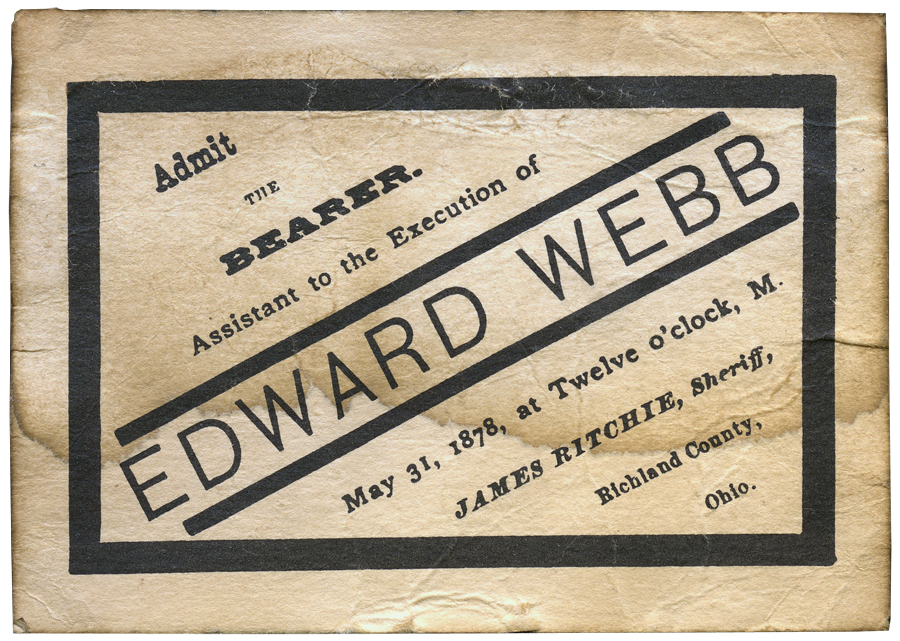

It was supposed to be conducted as a private, solemn affair. The Sheriff had a pine fence 18 feet tall of pointed pickets put up around the jail yard. Then he sent out a limited number of invitations that look something like a carnival ticket tastefully edged in black. Scalpers were selling them for fifty bucks a piece.

Sheriff Ritchie recruited the Mansfield Police force and a few volunteers—22 in all—to patrol the grounds, but a couple days before the event, when he saw the city’s hotels filling up with sightseers, he wired the Governor to send 60 more guards from the military.

Starting with the murder of William Finney, through the arrest, the trial, the sentencing and the hanging, details of everyone involved–their thoughts, actions, and often their attire–is preserved in newsprint.

The Lid Blows Off

The day Edward Webb was to die every train that rolled in Mansfield brought hundreds more spectators. Special excursion rates were advertised in the Ashland Press so groups could get to the spectacle without having to pay full price. Ho! For Mansfield! it said in bold print.

At 8:30 AM there were 100 people milling around the huge wooden fence at the jail yard. By 10:30 there were 2,000, and at 10:40 the walls were flattened, the guards had their rifles snatched from them, and 10,000 people cheered. A different reporter counted 15,000.

Men were drunk, women were trampled. The ugly crowd was stuffed in so tightly that there was no way Webb could even get from the jail to the noose. At 11 AM the mob made noises of breaking down the door and lynching the prisoner. The papers said it was remarkable that no shots were fired, but no one really knew just where the guns were at that point.

The Sheriff was, to say the least, alarmed. He wired the Governor asking what to do—hoping that when the privacy wall came down it had breached the law enough to give him a legal technicality by which to call it all off and send the boisterous multitudes home.

Outside there was chanting, jokes, cries of derision, cries of exuberance. It sounded like those minutes between touchdowns when the hubbub churns in excited choppy waves, as the crowd smells blood and senses victory.

At noon the Governor’s response to the Sheriff arrived over the telegraph: Hang him in public.

Coda

The place where Edward Webb met his maker is today a parking lot on Third Street just west of the Mansfield Playhouse. When the time actually arrived for him to go on stage, the crazy rabble went suddenly quiet, and the place was oddly still.

The noon bells had already tolled, the air sounded empty, disheartened. A dog barked down by the tracks, a woman hushed her crying child.

There wasn’t a lot of dignity in the public manslaughter of Edward Webb, but in the end the howling mob found enough humanity within to recognize the gravity of death with silence.