When the house lights begin to dim, and the footlights are rising like the first of dawn: that is the moment when the lines blur between worlds of daylight reality and limitless fantasy. The lights go down like your eyes closing for the night, and then, when the spotlight suddenly splits open the dark, whoever is on stage escorts the audience into a rare waking dream world we call theater.

A theater is a place where imagination is bound only by gravity…and on occasion, not even the laws of the universe apply.

No wonder theaters hold such power in a community, even long after they are gone.

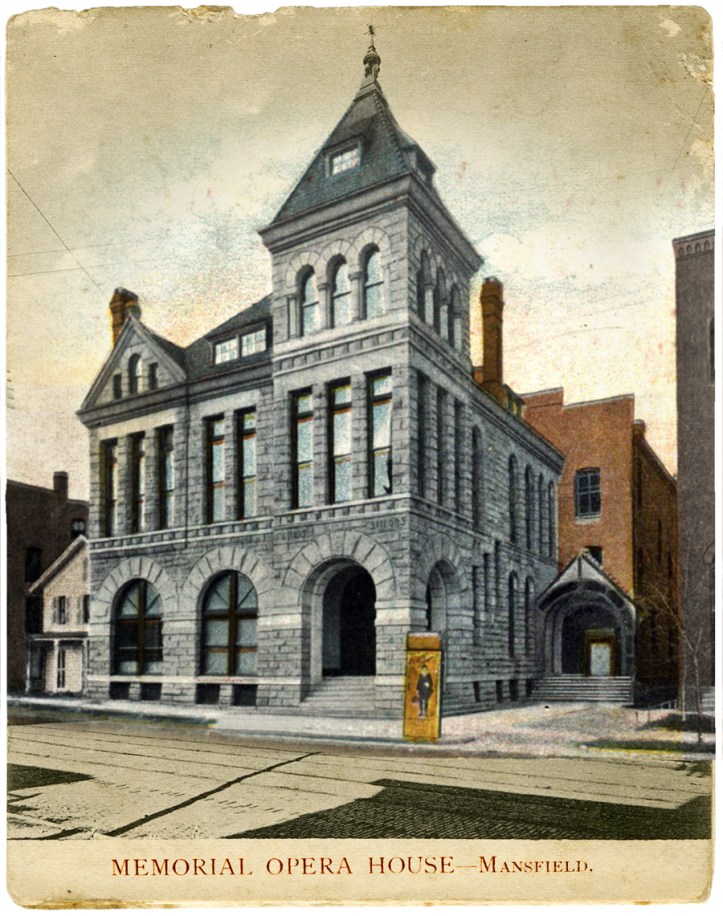

Our most enduring house of dreaming was called the Memorial Opera House, and it was well named because, generations after it is gone, it lives only in the memory of our town.

The ‘Memorial’ part came because the theater was built as one component of a larger civic complex that included the Memorial Library, and the meeting hall for Soldier and Sailor veterans of the Civil War, in memory of their fallen comrades.

The ‘Opera House’ part came during the first flowering of culture in Mansfield, when one generation of visionaries recognized the city’s metropolitan potential, and sought to provide the suitable accoutrements of a viable American culture. In the span of one generation, Mansfield got a public library, public transportation, a public parks system, a hospital, water works, the Reformatory, and a civic fountain in the public Square.

And the Opera House.

In 1889, as the city stood on the watershed between a common country town or a valid American city, the Opera House weighed in favor of national recognition. This was proven evetually in time, when Sarah Bernhardt chose to come to Mansfield.

She was the biggest performing star in the world for four decades, and on her last tour of America she played only the most legitimate theaters and vaudeville venues: like New York, San Francisco, and the Memorial Opera House in Mansfield, Ohio.

Too bad we don’t have pictures of ‘His Original DEATH DEFYING RIDE’ on the stage of the Opera House.

Genre

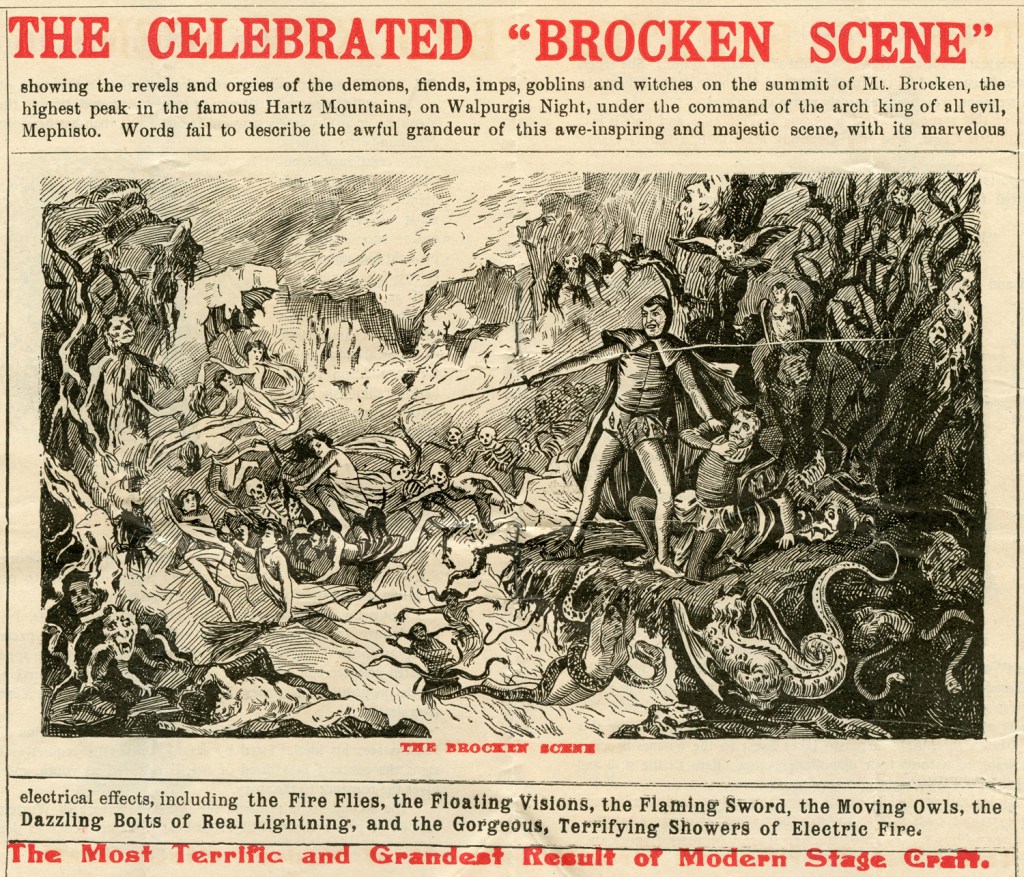

In terms of American culture, it is important to recognize that during the age of the Opera House—1889 to 1929—the concept of ‘opera’ embraced a rather wide spectrum of performance, ranging all the way from bawdy vaudeville, brass bands and burlesque; to maudlin drama like Ten Nights in a Bar Room, Peck’s Bad Boy and East Lynne; to highbrow art forms like Shakespeare, Faust, and Sarah Bernhardt in person.

Without question, the one play that spent more time on the Mansfield stage than any other was Uncle Tom’s Cabin. During the decades from 1890 to 1910, there were no fewer than seven separate acting companies touring Ohio with their own bigger and better dramatic rendition of the American standard, and they all played Mansfield as often as they could—sometimes within weeks of each other.

As competition between the Uncle Tom troupes grew stiffer, the productions got bigger. The first shows came with a cast of 15; then 30; then 60 with live animals. Then they started having parades before the show; and the last ones advertised two separate orchestras: one White and one Black; each with a Black or White singing quartette.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin was so popular it guaranteed a crowd, and folks who grew up in the Opera House era had all seen it a dozen times. The joke at the time was, “I’m always glad when Uncle Tom’s Cabin comes along, for then a fellow knows just what he’s going to see for his money.”

Comedy

One night in 1909, the curtain came up on a touring production of Hamlet and there was a surprisingly full house for Shakespeare. Unfortunately, the actor playing Hamlet had not been in this country very long, and he spoke with a German accent so thick anyone who was not German couldn’t understand a word of it.

The fray started with a few shouts from the balcony, and then a few flying foods, and then, when the Germans in the audience took offense to the ethnic slurs raining down from the cheap seats, the audience escalated into a full-fledged battle scene. Reporters said the brawl was Shakespearean in scale, and worthy of Act III.

Tragedy

The shows that drew the largest crowds to the Opera House were sentimental morality plays with lots of indignation, thwarted romance, and quarts of tears. Right behind those on the bills that sold the most tickets however, were any shows that advertised dancing girls. A 1910 program lists, “A cast of 70 professionals (mostly girls.)”

When the hugely popular vaudeville star Eddie Foy came to town for one of his many Mansfield encore performances, he wound up in the city jail for mistaking a local girl backstage as one of his touring ‘professional’ dancers. There were lots of headlines and sermons over that incident, but in the end, it only served to double the box office sales.

The Next Act

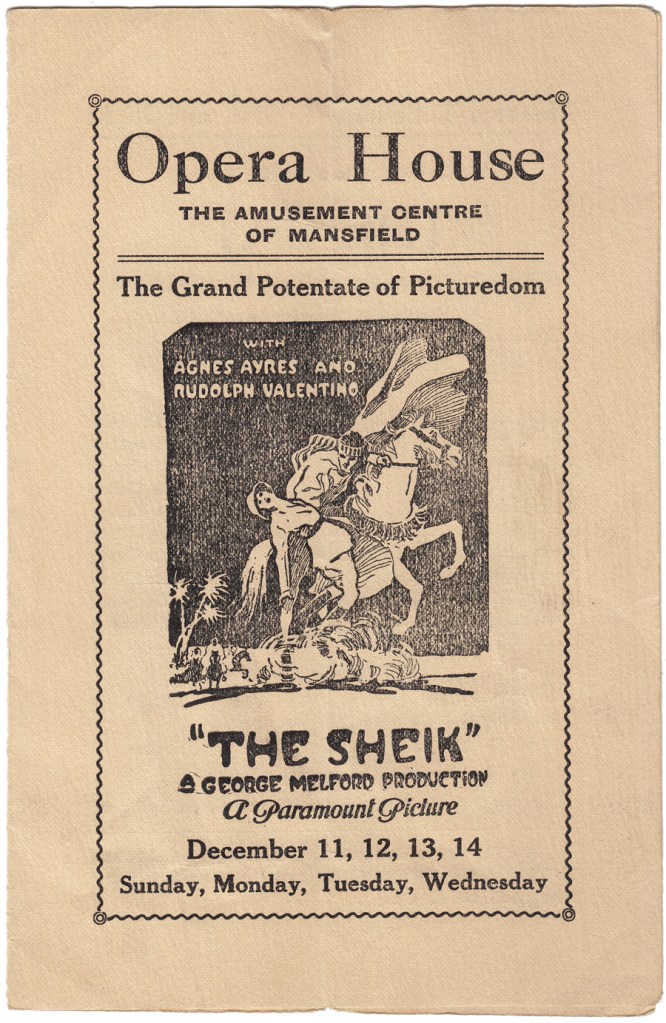

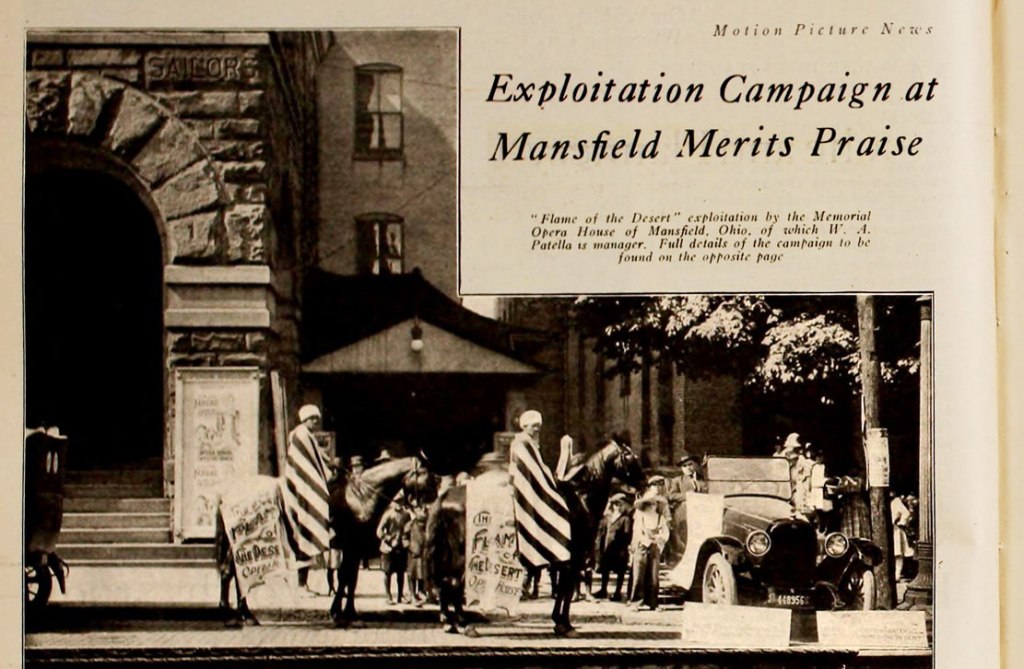

In the early 20th century, silent motion pictures came on stage as a novelty between acts, but within a few short years, movie houses popped up around downtown Mansfield that syphoned away the Opera House audiences.

In 1913, Thomas Edison announced that his Kinetophone system of adding sound to silent pictures was nearly perfected, and “the end of the legitimate stage is at hand.” The actual appearance of talking motion pictures didn’t come about for another dozen years after that, but live theater at the Opera House had to start sharing time with movies on the stage.

Facing ruin by 1927, the theater was finally remodeled as a cinema, and reopened as the Madison Memorial Theater. It proved to be a profitable metamorphosis, because it qualified them to host the first talking picture—The Jazz Singer—and sell 3,000 tickets in one day.

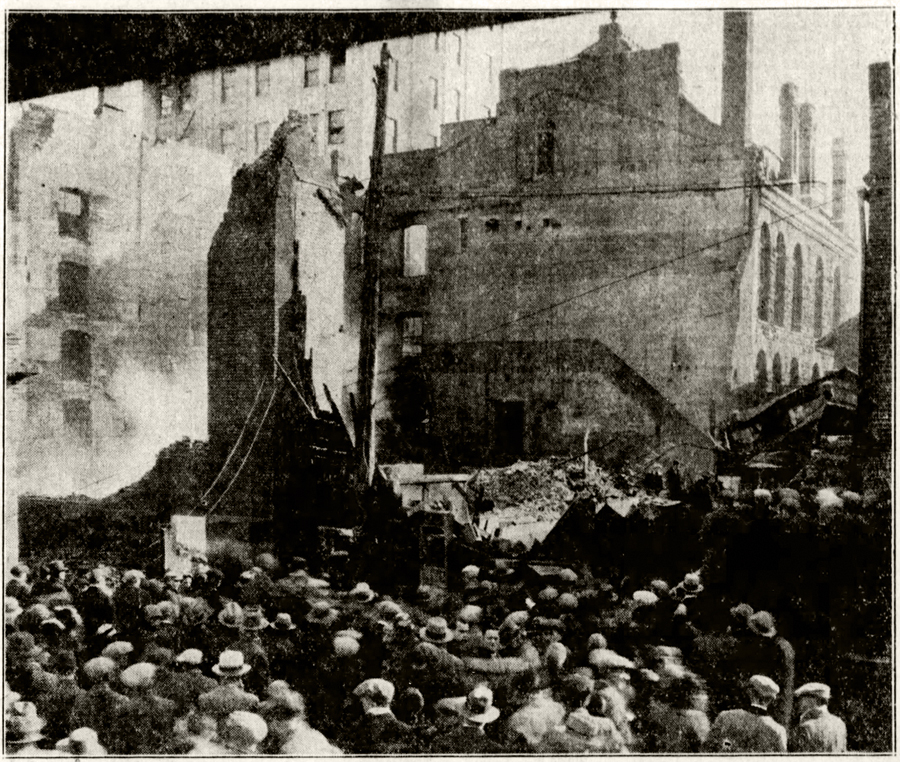

The curtain came down on the Memorial Opera House in 1929, when the building burned to the ground. It was rebuilt as a movie house, and opened in 1931 as the Madison Theater.

Exeunt

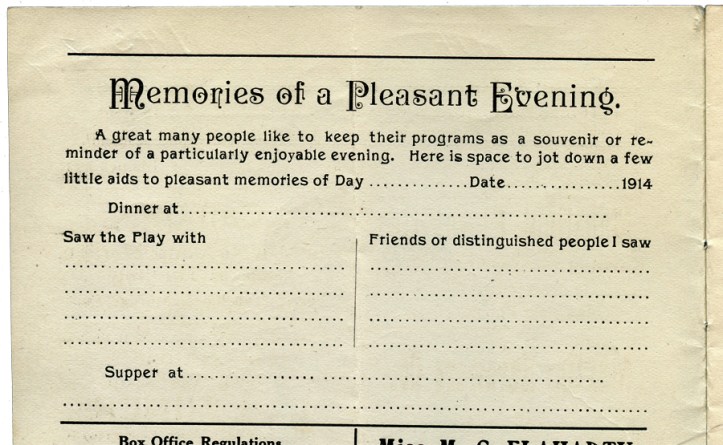

In terms of history, dreams and memory are not that different. People often preface their memories with, “it seems like a dream I had once;” or “I’m not sure if it was something that really happened, or whether I dreamed it.”

In terms of a community, and our communal memory, the dreams fade through the years like a play we once saw: and maybe there is an old program to recall some moment which stood out as brilliantly illuminated in the surrounding void of our darkened theater.

Post Script:

[…] More on the Memorial Opera House […]

LikeLike