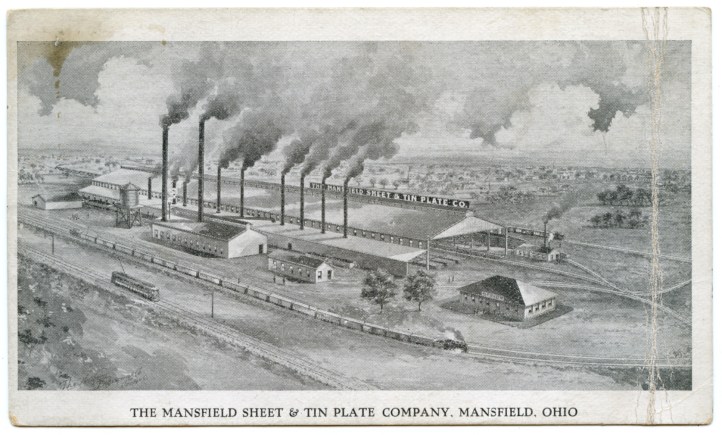

The Hotel Lincoln in Mansfield could be given a rank of several stars among the storied lost landmarks of America, but maybe not in any way you might expect. It wasn’t a flashy place: it stood overlooking the Steel Mill.

Maybe that doesn’t seem like much of a draw, and maybe it seems like that is why the place slipped out of local legend in recent generations. But coal dust on the breeze was only one aspect of the Lincoln, which was a multi-faceted gem: the food was terrific; the bands were legendary. The drinks were deep even when alcohol was illegal. The company was loud and charming and occasionally famous, in an atmosphere smoky with cigars and ribs and Creole spices.

There was much to recommend this establishment among the nights and days of the 20thcentury, but one particular feature made it rise above all the others in a city known for its hotels: for nearly half a century, the Lincoln was the only hotel in Mansfield where African American travelers were welcome.

Highway Safety

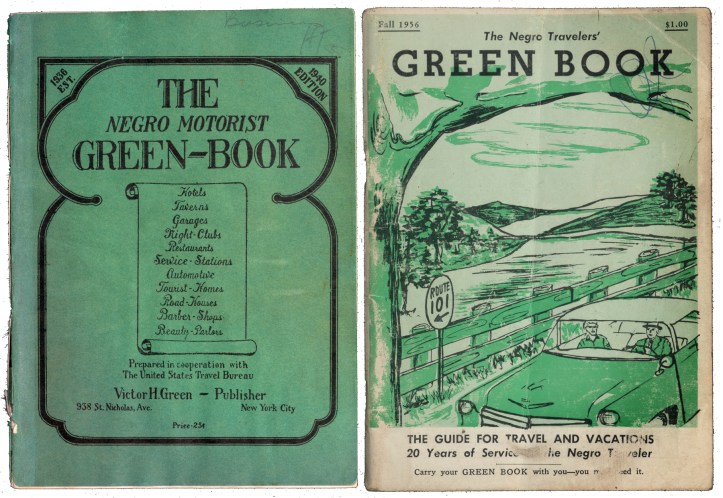

The whole point of a Hotel is to provide sanctuary for travelers where they can feel as safe as if they were home. In the early decades of the 20thcentury, people of color in the United States were not guaranteed any safety once they traveled away from their home neighborhoods. That is why a special resource was devised to provide them with the names and addresses of hotels and restaurants, restrooms and gas stations, night clubs and theaters in communities across the country where Black people were welcome.

It was called the Green Book: The Negro Motorists’ guide.

From 1936 to 1966—except for the period of WWII—the Green Book was updated every year with contact information necessary for a safe journey, and a safe vacation in all the United States.

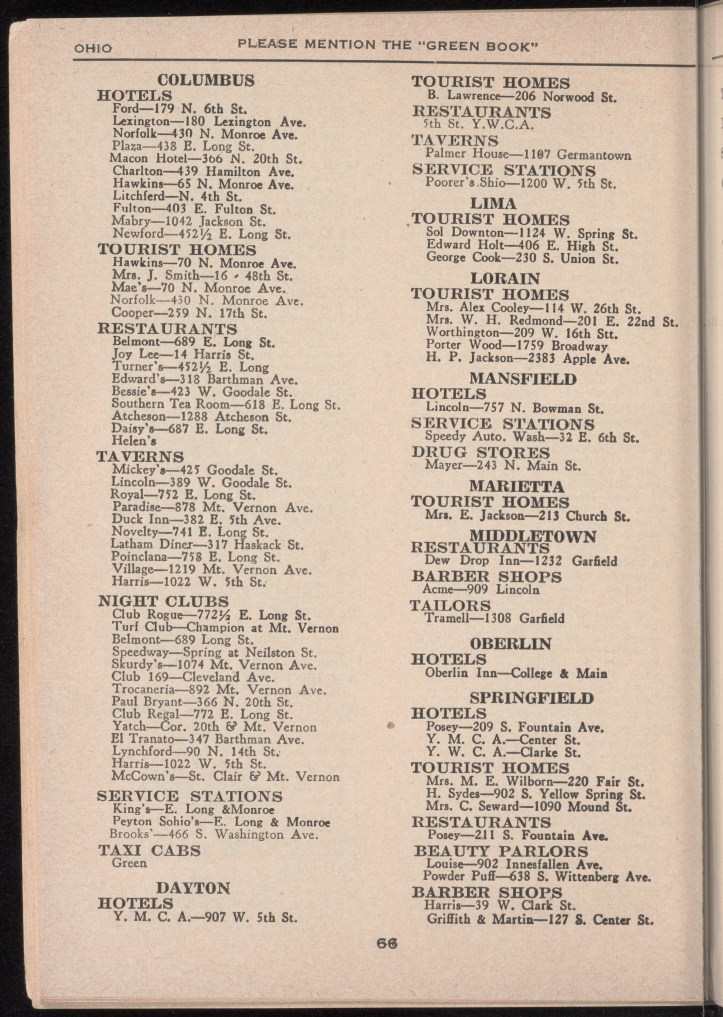

During those three decades, there were 16 years when Mansfield was listed in the Green Book. And in all that time there was only one hotel in the city designated as a place where Black guests would be welcome: it was the Hotel Lincoln, 757 Bowman Street.

The landmark hotel and restaurant was built around 1919 across from the new Steel Mill by a Greek immigrant who knew he could sell lunch and beer to mill hands. Nick Kovacevic called his place the Road House. He spoke American well enough to do business in Mansfield, but he had been raised far enough away from the United States that he came without any of the American preconceptions about racial relations.

He was happy to serve Black customers.

In the ensuing decade, as more and more African Americans migrated to Mansfield from the South to work at the Steel Mill, the dining room on Bowman Street was a center of the Black community.

In fact, after the place was renamed the Hotel Lincoln by a new African American owner in 1924, the dining room at 757 Bowman Street became the de facto town hall for Mansfield’s Black community. Politicians looking for Black voters needed to make their speeches at the Lincoln; and when City Council addressed itself to the local Black populace, the event took place in the Lincoln dining room.

The new owner was Ernest L. Smith and he was not hesitant about exercising the civil rights of his community. In 1930, he sued the Arris Theater on Main Street because an usher told him to change his seat to the Negro section of the room.

Mr. Smith was having none of that in his town. He organized a Black political bloc of Mansfield constituents called the Attucks Club in order to address problems of city segregation.

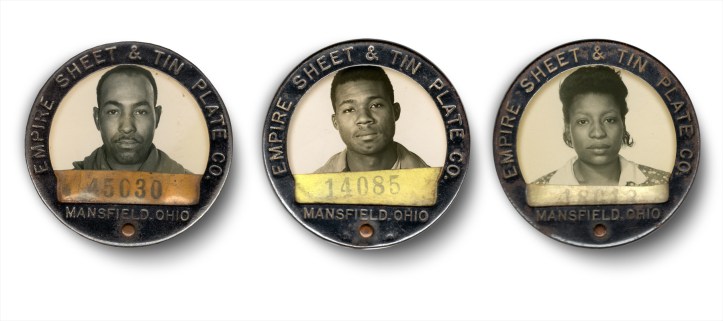

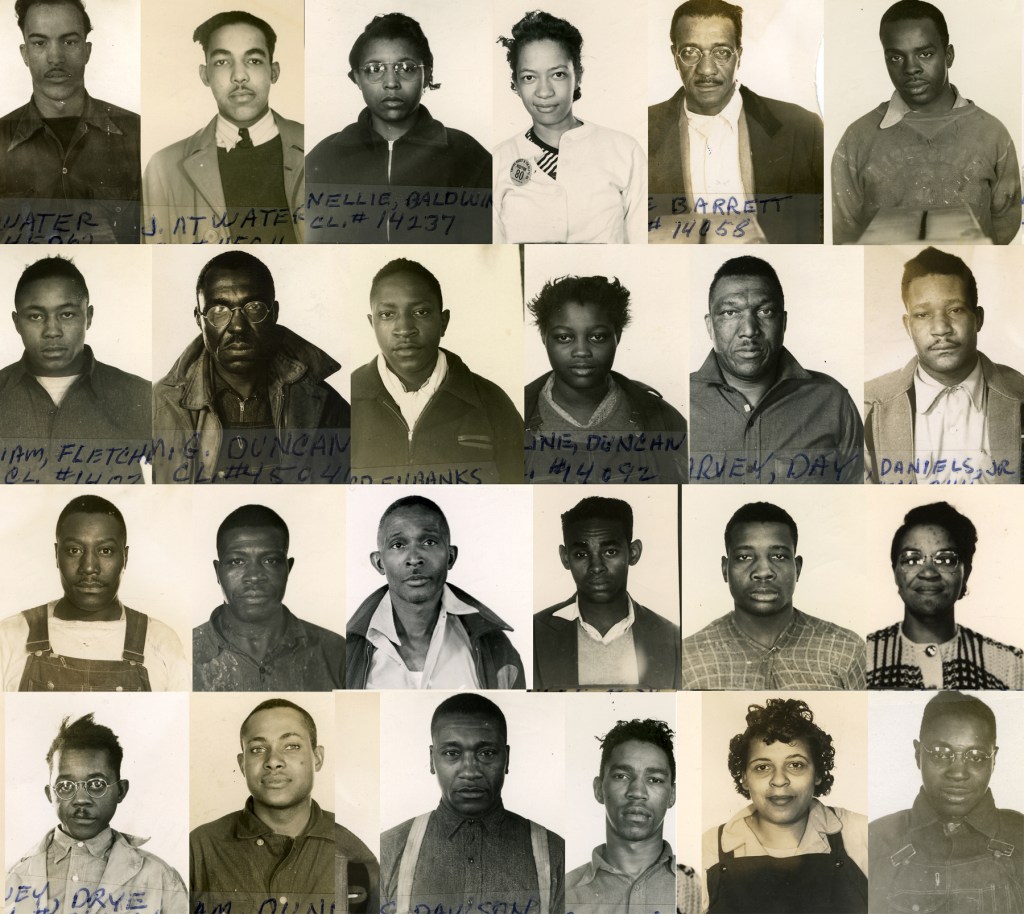

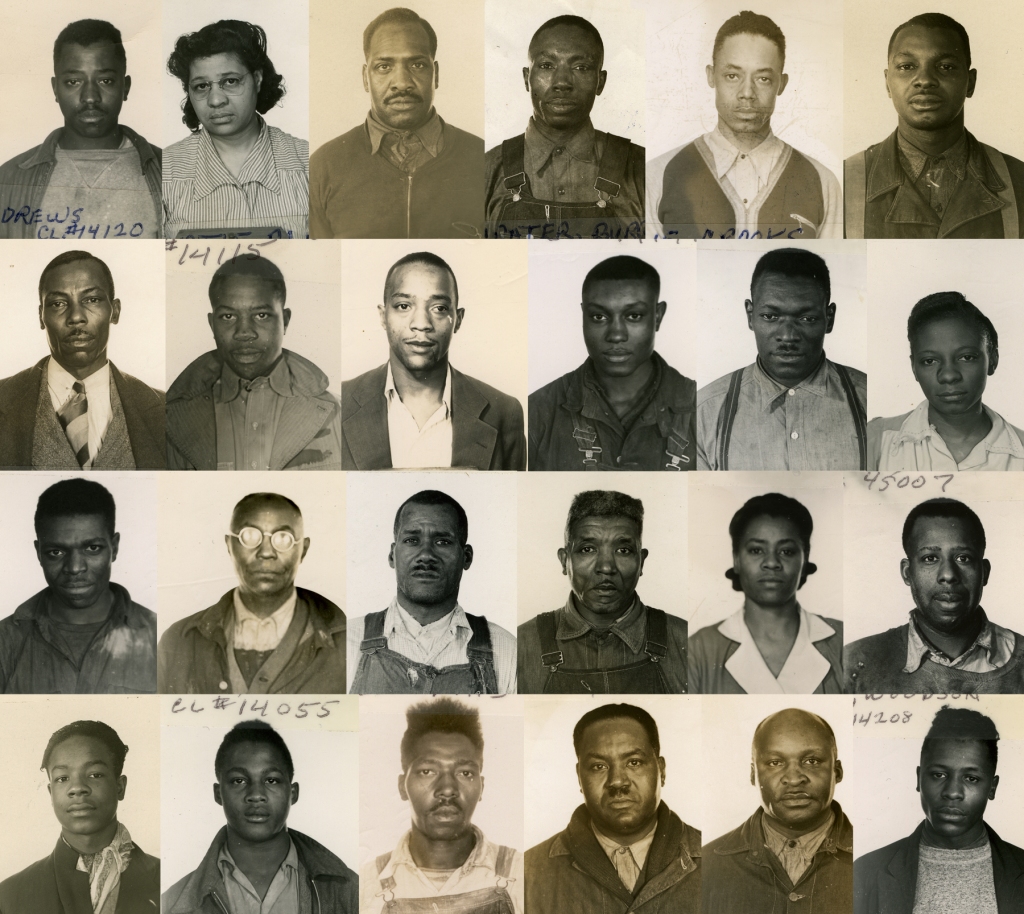

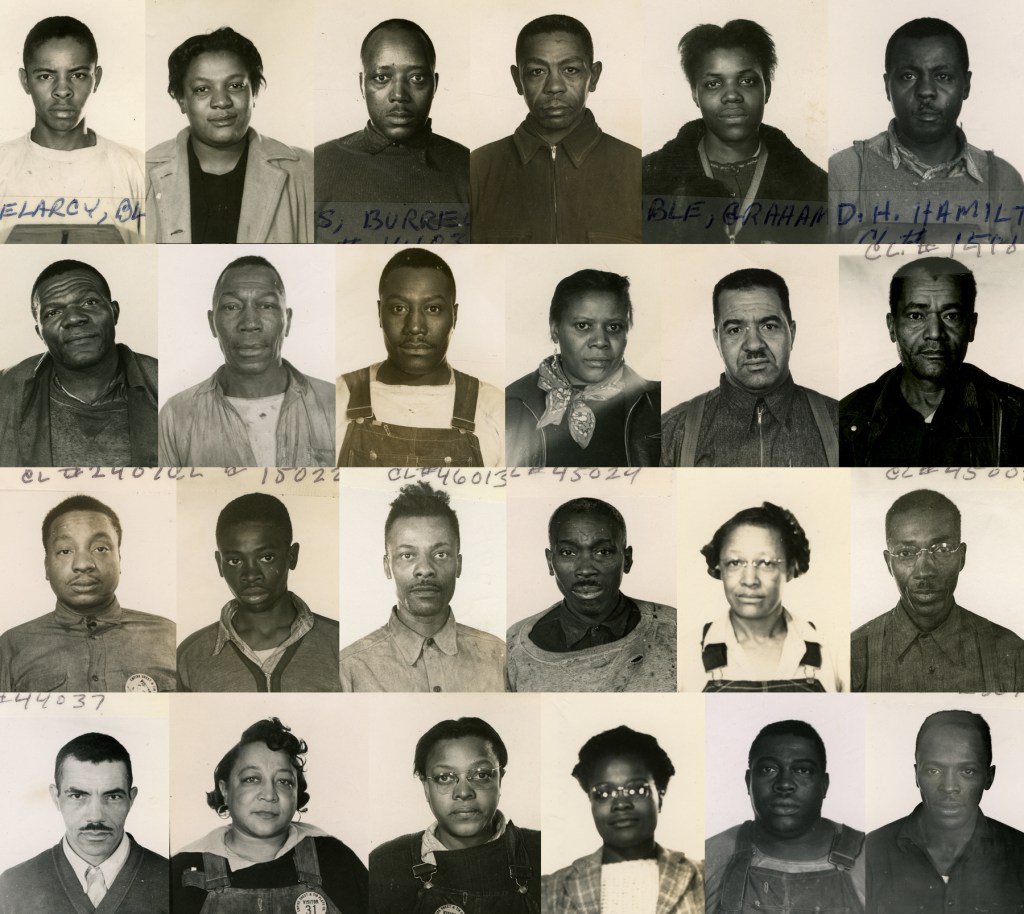

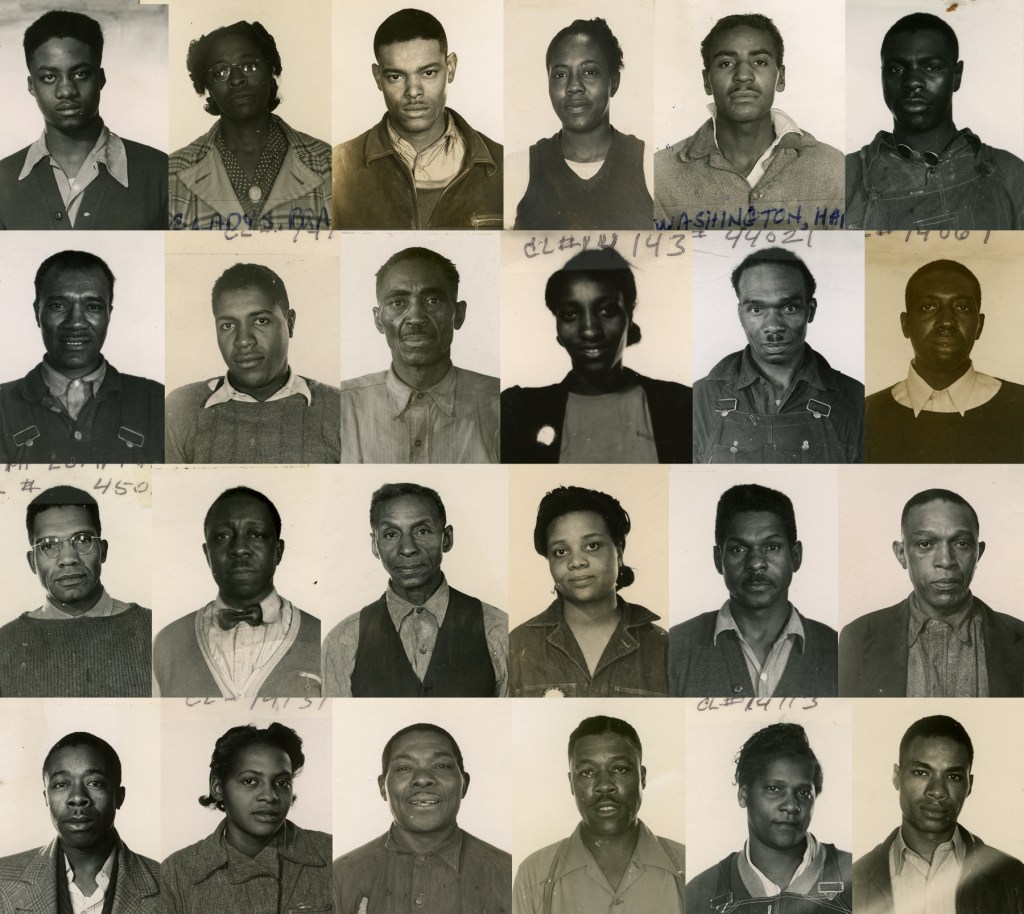

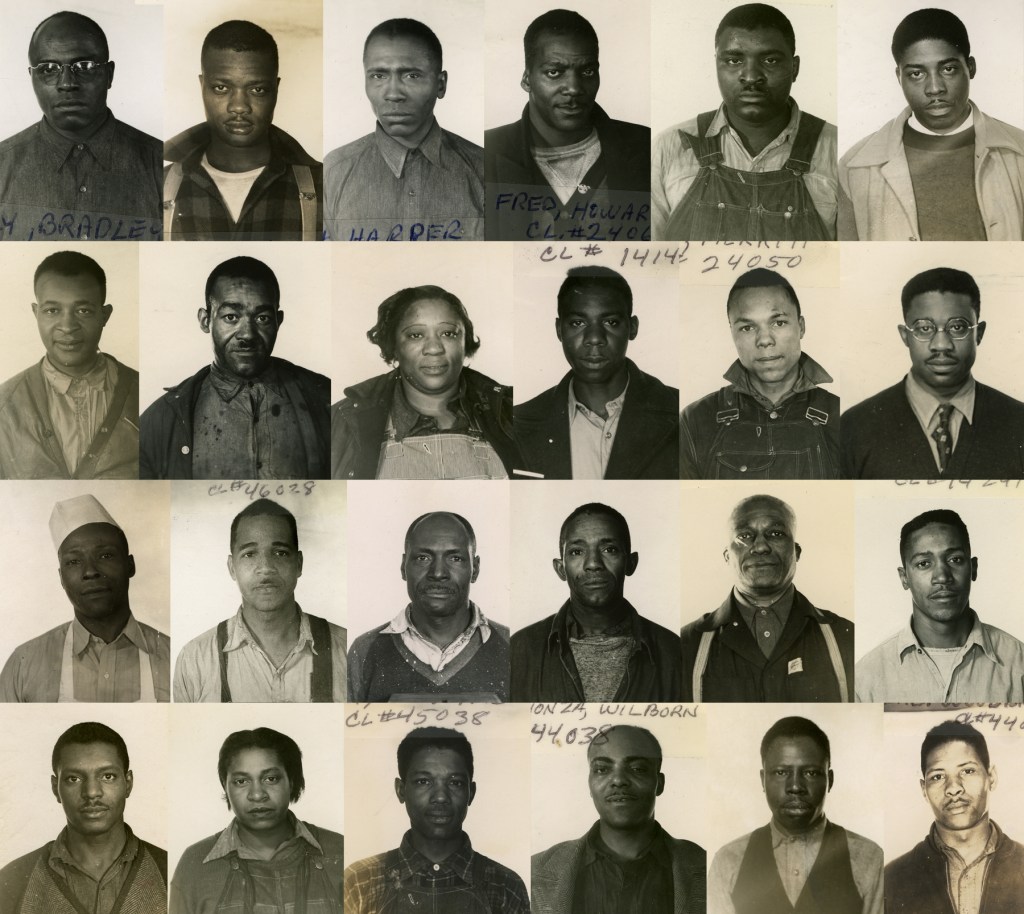

These portraits were taken in the 1940s for ID badges at Empire. (Salvaged by Ophinel Davis.)

Coloring the Map by Neighborhoods

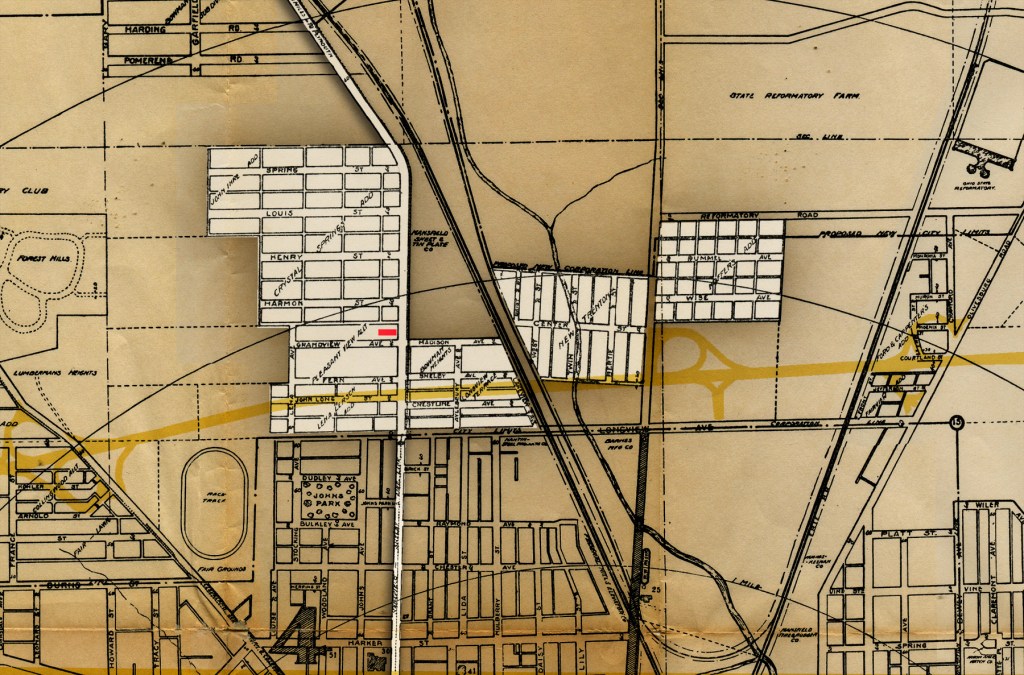

Before the Mansfield Sheet & Tin Plate Co. was built in 1914, the Black population of Mansfield was living mainly in neighborhoods located in the eastern and southern parts of town. When the Steel Mill put many of those African Americans to work, and then drew many hundreds more Blacks to Mansfield from Alabama, Georgia and Tennessee, naturally they all wanted to move closer to their job.

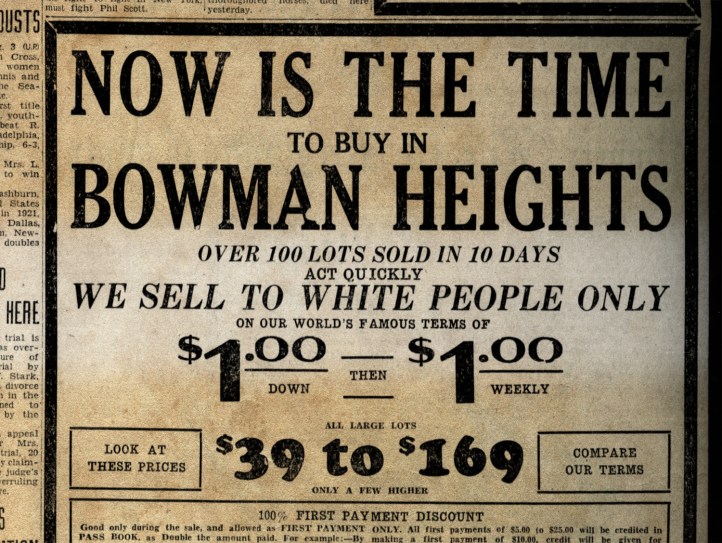

The north end near the Steel Mill was rapidly opening up new streets, additions and neighborhoods in those years, yet the Black population was pointedly excluded from that expansion. In fact, the city’s only almost-race-riot took place in 1917 when a Black man bought a house a block from John’s Park near the Steel Mill and the white neighbors freaked out.

No one ever threw a punch or a brick, but the demonstrations of numbers, with crowds of raised voices, was as close to a riot as this ordinarily polite city ever got. After a few hot days of angry posturing, the sale was rescinded and a City Planning Commission was formed to keep neighborhoods neatly sorted according to color.

When the Hotel Lincoln was built, it was a couple hundred yards north of Mansfield city limits. The neighborhoods that grew up around it were known at the time as Little Africa, or, in the papers, as “the negro colony in the northern section of the city.”

A Reputation Earned Without Reservation

As the only hotel in North Central Ohio where the Green Book said Negro Motorists could be sure of a room and a meal and an indoor restroom, the Hotel Lincoln was elegantly poised to benefit from the indiscriminate whims of chance. No one needed a reservation, so lots of unexpected guests showed up. Any person of color driving between Chicago and New York on the Lincoln Highway when it came time to eat or sleep, had to either press on to Akron or Lima, or else take the turn at Bowman Street and head a mile and a half north to the Lincoln.

Satchel Paige did it once, in the off season, and Ernest Smith talked about the famous Negro League pitcher’s appetite in an interview printed by the Cleveland Gazette. Apparently Paige could eat more than anyone Smith had ever seen, and when Smith tore up the baseball hero’s bill, Paige left a tip on the table big enough to cover two meals.

The Mansfield News had a weekly column called “News of Colored Circles,” but it never gave more than a paragraph to Smith and the Lincoln occasionally. The Gazette, on the other hand, was an African American paper that spent more ink on stories like those Smith had to tell about his hotel.

Smith’s favorite memory was about Cab Calloway. Most touring Black entertainers, like Duke Ellington or Louis Prima, booked only one performance in Mansfield so they could move on to Cleveland for overnight accommodations. Cab Calloway was booked into the Madison Theater for two days though, which meant he had to overnight here.

Ernest Smith went to the theater while the Swing Band was setting up, and invited the famous jazz singer to the Lincoln for free room and food. Knowing that Cab would be exhausted after a day of four performances, he promised the performer they could sneak in the back door and avoid being mobbed by night club fans in the Dining Room and dance floor.

Cab Calloway agreed to walk in the back door, but it took only about ten seconds till he was out in the crowd laughing and singing; putting on his fifth show of the day.

What Matters

The Green Book ceased publication in the mid-1960s after the Civil Rights Act made it illegal for hotels, restaurants and filling stations to refuse service because of race. Mansfield was not listed in the last few issues of the guide book though, because Ernest Smith died in 1961 and his dining room across from the Steel Mill went quiet.

There was a revived business called the New Lincoln Hotel that opened in 1963 on Second Street, but it never really caught on with out-of-towners like the original site.

The Hotel Lincoln is long gone from Bowman Street today, but it is worth preserving in our living memory.

This was an excellent piece to read,I think my mom might be one of the only persons still living that remembers this.

LikeLike

When did the Lincoln Hotel become the Ebony Hotel and was the address still the same?

LikeLike

The Ebony Hotel (approx. 1956-1969) stood farther out Bowman Street from the Lincoln, and they were both open at the same time for a few years.

LikeLike

Who was the owner of Ebony Hotel in 1969 and what was the address?

LikeLike

Joe Wilhite, 831 Bowman St.

LikeLike

When did Thomas Brightwell become the owner and if wasn’t the owner then who was?

LikeLike

Very informative. Thank you for sharing.

LikeLike