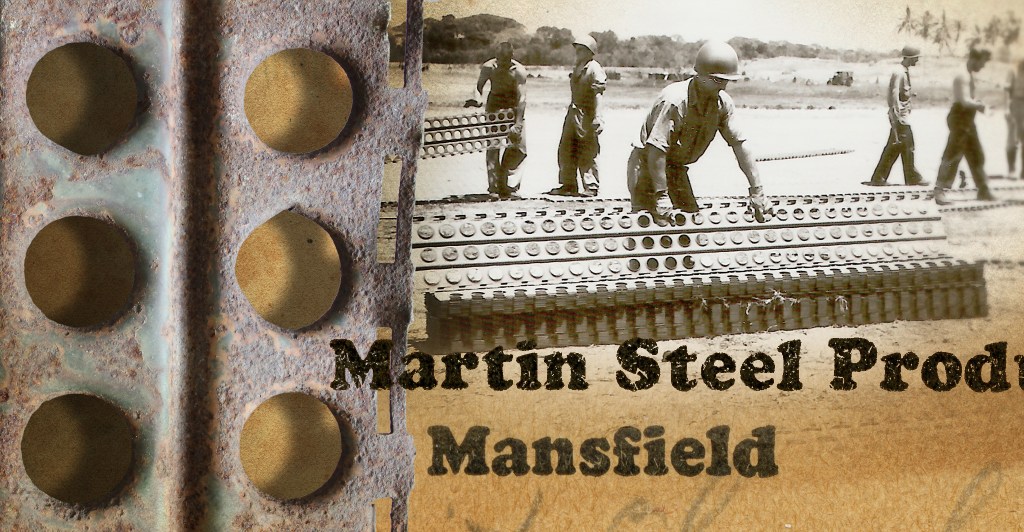

How did American forces of WWII gain traction in Europe after getting a foothold on the Normandy beaches of D-Day?

Answer: Martin Steel of Mansfield, Ohio.

France and Germany are made of mud and sand and mountains, none of which is particularly easy to drive over, or march over, or land a plane on. So the U.S. Army devised a method whereby difficult earth could be covered with a layer of textured steel plates to create a serviceable road surface or runway surface. It was called PSP: Perforated Steel Planking.

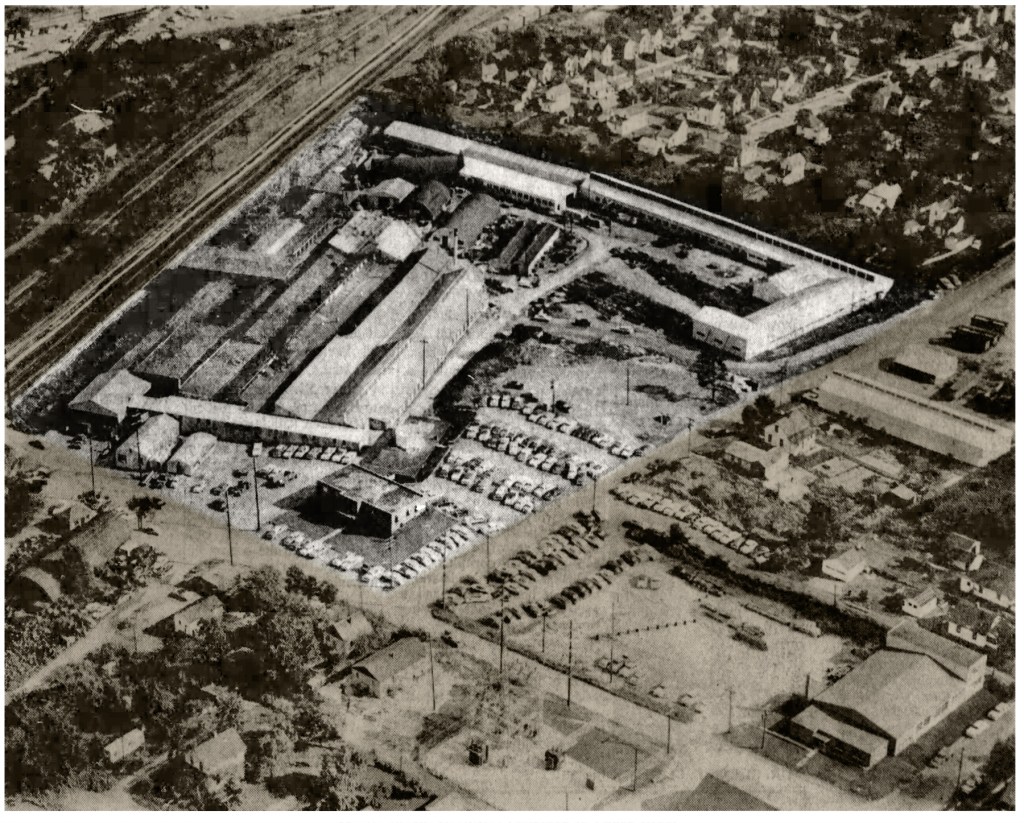

It was manufactured on Longview Avenue right next to the tracks.

That was how the Army Air Force was able to land planes on all those little South Pacific islands made of sand: instant runways assembled from Mansfield steel.

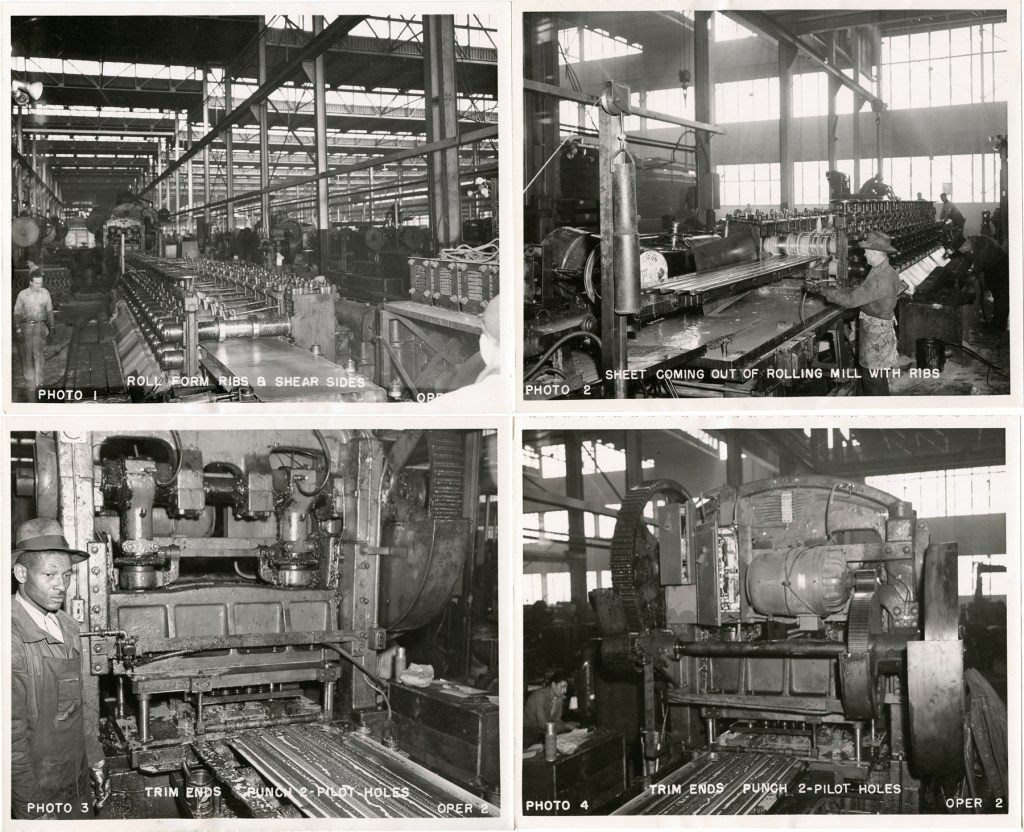

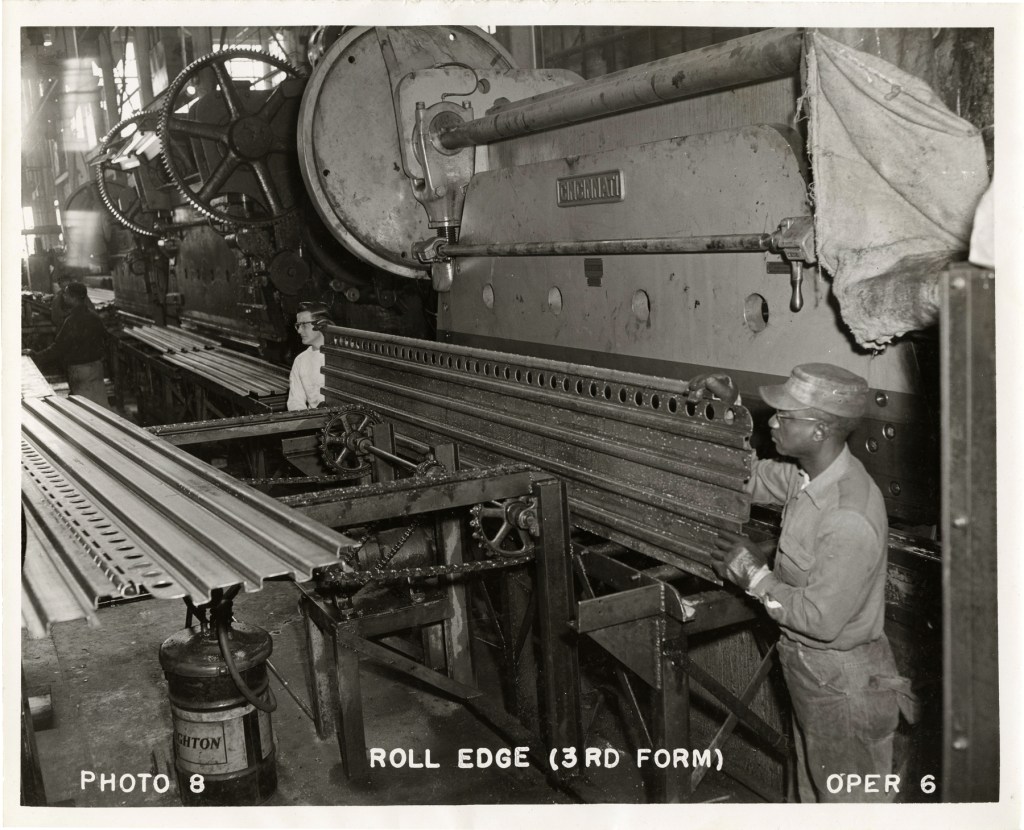

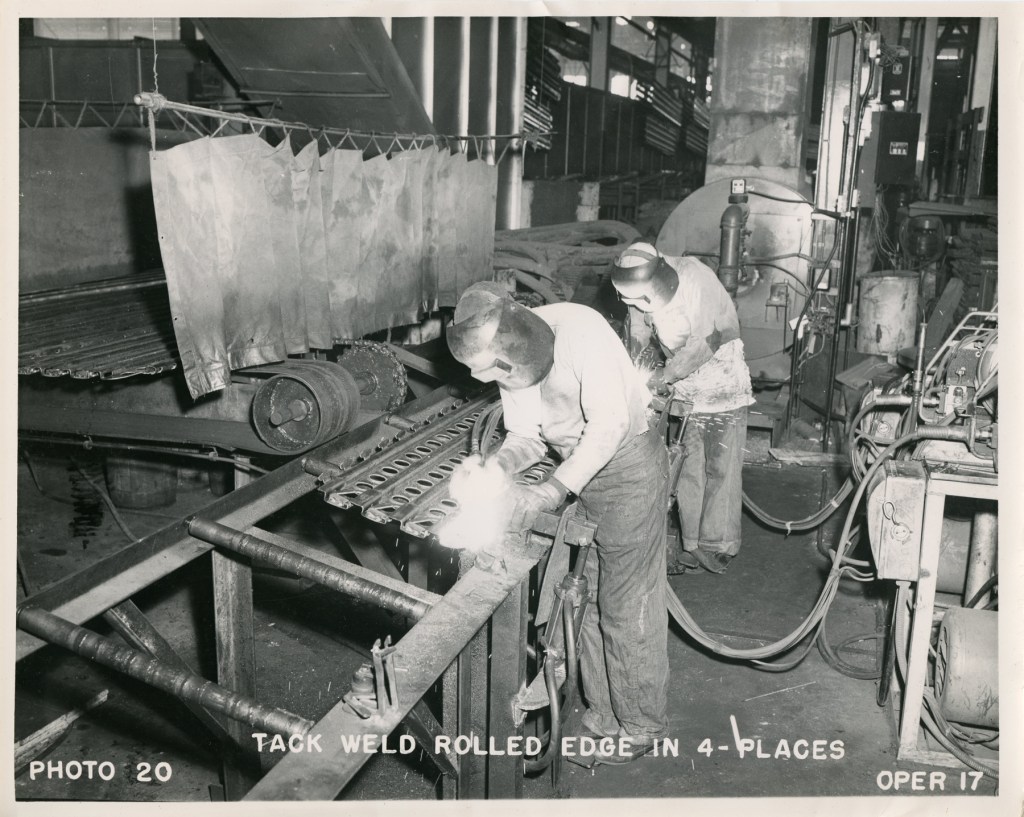

Wartime Production

Martin Steel was not the only plant in America fabricating the steel planking: by 1945 the U.S. had shipped 477,000 tons of it overseas, and it took 29 factories working around the clock to crank out that much massive material.

But Martin Steel led the way. Late in 1941 they were commissioned to document the entire process of taking a plain sheet of steel and turning it into essential wartime supply through a series of 25 photos made at the Longview plant. This Mansfield photo essay became the instructional manual for steel plants across the nation.

And it provides us with a rare glimpse inside the North End factory complex.

Martin Steel

The Martin Steel Production Company was founded in 1895 on North Adams Street, and grew so profoundly through its first decades that the operation had to move to Longview Avenue in 1920 so it could build a plant five times larger.

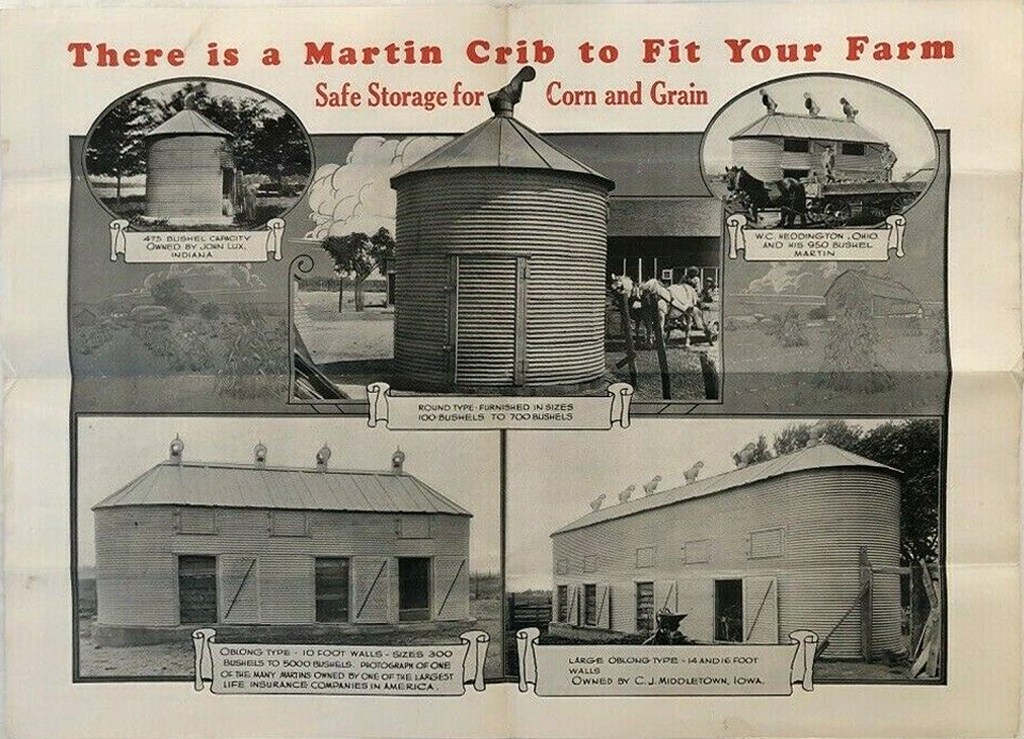

They were known around the nation and the world for their steel agricultural products, primarily farm buildings like corn cribs, garages and silos.

History & Rust

Tough as it is, steel does not last forever. Especially on old battlefields. Yet, even in ragged pieces it has made it farther down the timeline than those hands who shaped it, the company that shipped it, and the warriors who depended on it.

Last year, a corroded old chunk of PSP was found in a woods behind Utah Beach in Normandy, and, though reduced to fragile flakes of rust by the ravages of decades, it is clearly recognizable as made in the U.S.A., perhaps one of those pressed out of Mansfield steel.