It was in the 1920s when Mansfield’s Black community developed a coherent voice in the city with a significant band of activists.

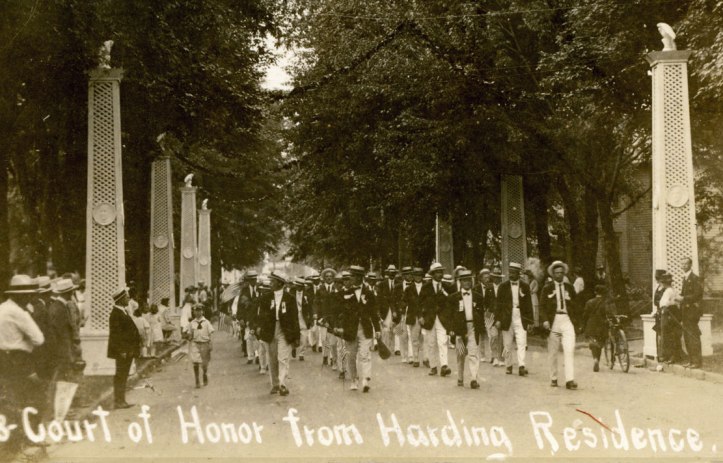

There is a particular date to which we can document the initial appearance of Mansfield’s first Black caucus. It is July 31, 1920. That was the day the activist leaders of our city’s Black community stepped forward to make themselves seen, and we know this because the moment was captured clearly in a photograph of historic certainty.

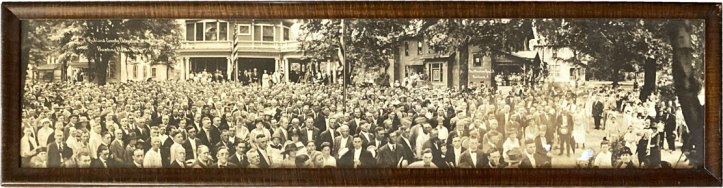

The sepia toned photo is 8” x 34,” which was a common format of that era known as a ‘yardlong.’ The photographer set his special camera up in the street to capture this historic occasion when Warren G. Harding officially launched his famous Front Porch Campaign for President by addressing thousands of voters from Richland County.

A parade of nearly 400 cars drove from Mansfield to Marion on Saturday morning, July 31, and thousands more folks took Erie Railroad specials from Union Station and from Shelby to cheer Warren G. Harding at his home.

The huge crowd marched through the streets of Marion from the railroad station to Mt. Vernon Avenue, and all newspaper reports of the event said unquestionably the highlight of the parade was “The Colored Jazz band” from Mansfield.

The parade culminated at a political rally where several thousands of people stopped cheering, yelling, applauding and singing long enough to listen to Warren Harding speak. And while he was still standing there on his front steps, everybody paused and faced the camera to have their picture taken.

The only black faces in that sea of white voters were the organized advocates from Mansfield.

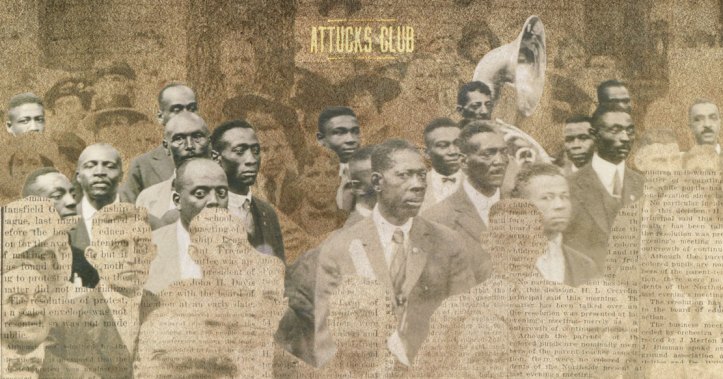

In succeeding years, for different purposes, this group of activists assumed different names, but that summer afternoon in 1920 the Black leaders put themselves forward as the Colored Voters Harding Club. In a few years, they would be called upon to speak to issues in Mansfield as the non-partisan Good Citizenship League; they addressed voting strategies as the Attucks Club; and within a decade that activist caucus would be known simply as the Mansfield NAACP.

In the Crowd:

From news articles in the Mansfield News regarding activist organizations in 1920-’22, we can expect the faces in this crowd include: Arthur Cobb, Ben Patterson, Thad Bertrand, Robert Reynolds, Ed Tillman, James Hogan, Sol Blaine, Ernest Smith, Edgar Burch, Leonard Wisdom, William Hawkins, G.L. Bynum, Frank Cromer, Fred Atwater, Herbert Towles, Sam Johnson, Henry Pearson, Luther Gossett, John H. Davis, W.H. Cash, Thompson Jackson, Rev. H. Teague, and Rev. George Smith.

Why 1920?

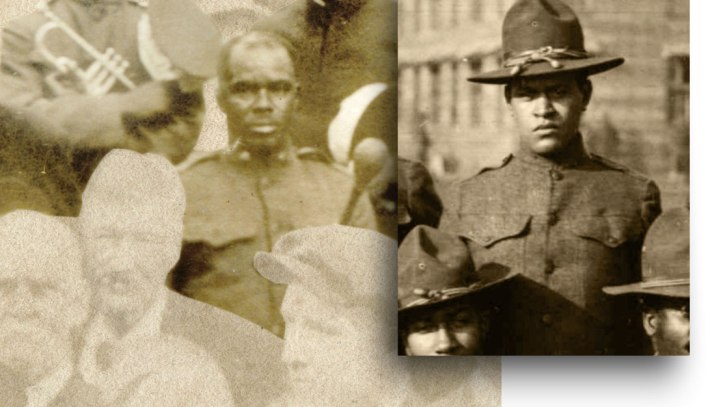

There is a reason why some members of Mansfield’s Black community felt they had an opportunity to be heard after decades of being ignored. These were men who had put on the uniform of America’s armed forces and shipped overseas to represent our nation in World War 1. They had put their lives on the line no differently than 2.8 million other Americans serving their country for world peace.

When the nation asked for young men to get their boots muddy in the trenches of France, the State of Ohio gathered 120,000 men to learn the arts of war at Camp Sherman in Chillicothe. Of that force, 2,000 were African American. They were housed in their own segregated barracks and served in their own segregated battalions.

Eight of those Black men came from Mansfield. They left in 1918 on their own segregated train.

When they went to Marion on July 31, 1920 to march amid three thousand white faces, these men wore their WW1 uniforms to evoke the respect they deserved from their countrymen.

Why Harding?

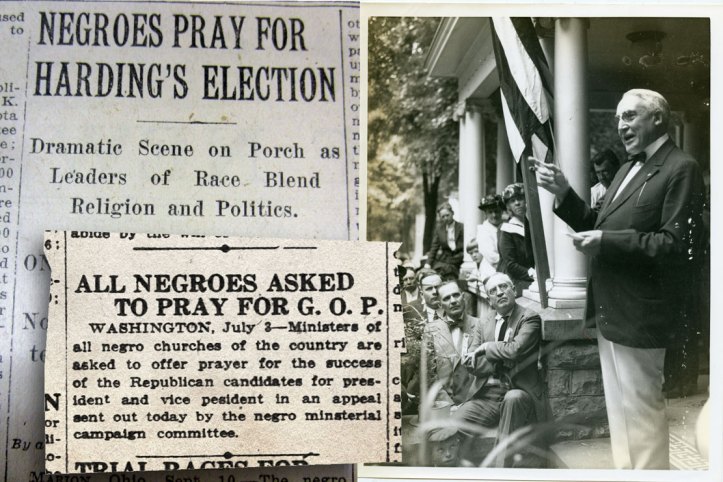

The Black voters of Mansfield stood up for Harding in 1920 because he was the first presidential candidate in memory who truly acknowledged Black culture in America. He actually received Black voters at his home, and did it so publicly it made headlines across the nation.

And Harding was willing to lay his presidency on the line in 1921 when he gave a speech in Birmingham that shocked the nation, as the first president to speak directly to the American South with a call for the end to lynching, and advocating authentic equality among races.

Warren Harding, on the other hand, said, “The Black man should seek to be, and he should be encouraged to be, the best possible Black man and not the best possible imitation of a white man.”

His words in 1921 clearly anticipate those of Dr Martin Luther King Jr in 1963. Harding said, “These things lead one to hope that we shall find an adjustment of relations between the two races, in which both can enjoy full citizenship, the full measure of usefulness to the country and of opportunity for themselves, and in which recognition and reward shall at last be distributed in proportion to individual deserts, regardless of race or color.”

Segregation at Bowman School: 1925

Following the 1920 election, the Black caucus rebranded itself in order to address issues in the Mansfield community.

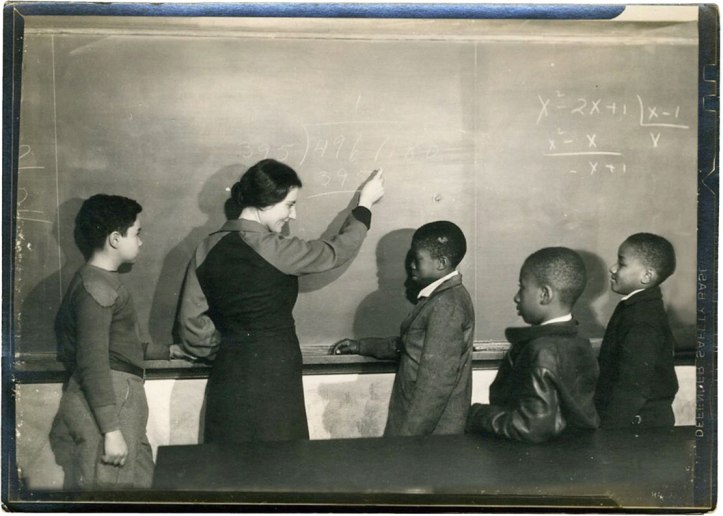

In the spring of 1925, there was a PTA meeting at Bowman Street School where it was suggested that all the grade school kids might be better served if the young Black ones had their own classrooms. There were no Black parents at this meeting.

Word of the proposal, however, was published in the Mansfield News.

Black leaders, of what was then called the Northside, established a non-partisan organization to speak about the Bowman School proposal as a unified voice. It was called the Good Citizenship League.

The Board of Education carefully explained that of the 54 Black children at Bowman School, all but 16 were recently emigrated from the South where they did not have the benefit of education, and required special consideration.

They hired two Black teachers, set aside rooms on the Third Floor, and implemented what they saw as the best solution. The Black community saw simple Segregation.

There was a mass meeting at the Friendly House; there were petitions and protests; but regardless, the Third Floor was known in the paper as ‘Colored Bowman’ until 1946.

The State of Ohio had prohibited school racial segregation in the mid-1930s, and every year five leaders of the Black Northside presented formal protest to end Colored Bowman classes. The Board of Education every year resolved to study, research, investigate, seek advisement on the subject until 1945 when a law suit finally put an end to that era of Mansfield history.

The complex human heart of any community:

By the 1940s, there were 88 students in Colored Bowman with three teachers. Other classes had one teacher for 40-45 students.

Every time the husbands raised a petition to end Colored Bowman classes, the mothers circulated their own arguments in opposition. The Good Citizenship League could get nearly 200 signatures on their petitions; the Black mothers easily got 400.

In this way, segregation of the school lasted a full decade past the year when Ohio formally prohibited racial segregation.

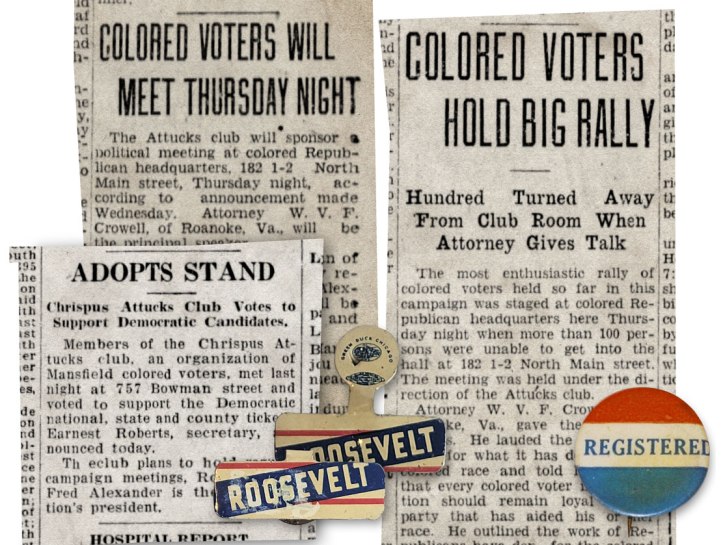

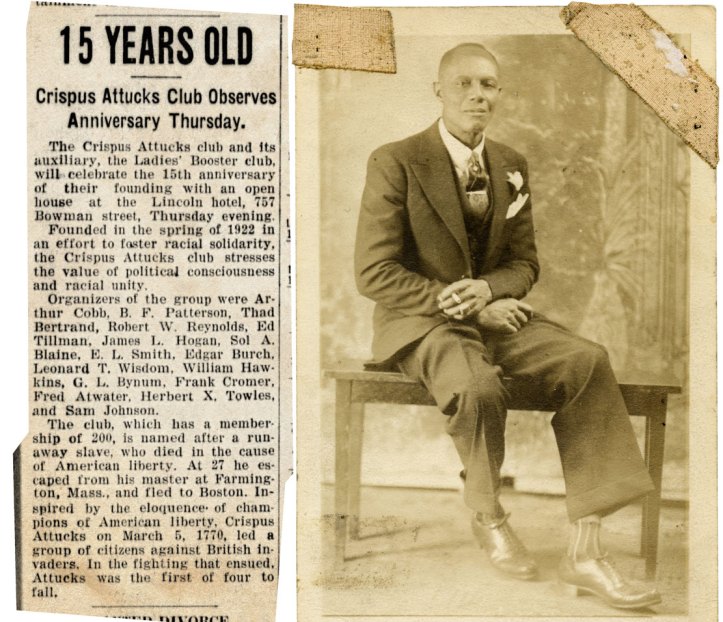

Attucks Club

Most issues that the Black community’s leadership faced in Mansfield required non-partisan unity, and they knew that politics served more often than not to divide the community. Yet there was a need for a strong political voice from the Northside, and to this end evolved the Attucks Club.

Members of the Attucks Club gathered to hear candidates and to campaign for greater turnout at the polls, and to address all things that took place at in the voting booth.

The club originated in 1922 and lasted until the beginning of WWII.

In the early years of their organization, the Attucks Club frequently met at the Colored Republicans Club on North Main Street, but as the tides of current evets swelled into the 1930s Great Depression era, the meetings were held at the Hotel Lincoln on Bowman Street.

And it worked. He was awarded $50—which is almost $1,000 today—and afterward all of the spoken and unspoken theater segregated seating in Mansfield faded away.

The New (old) NAACP

The activists of Mansfield’s Black community needed to find a new organizational structure in the very changed city that emerged from WWII. For one thing, the Northside Black community doubled in population as the city’s industrial bonanza drew more Black laborers to town from Southern states.

In searching for a new identity, the Black leaders simply re-activated a very old identity: the NAACP. There was a Mansfield chapter of NAACP established in 1920, but the early decades of its function in town were limited primarily to educational speakers and social gatherings.

With new challenges to Black culture in Mansfield during the 1950s, NAACP got a new charter in 1955 and a new presence at the table to address essential issues like housing, employment, hospitalization, and criminal justice.

Yet its first formal protest in the city didn’t take place until 1964 when, as the focused voice of Mansfield’s Black families, NAACP put an end to one of Mansfield’s longest standing racist pastimes: Minstrel performances in Blackface. For generations, Blackface was an annual fundraiser for AMVETS, and practiced thoughtlessly in entertainments ranging from community theater to the stage at Mansfield Senior High.

When NAACP finally raised its voice, the insult ended forever.

And we might well imagine this voice was given strength the year before, in 1963, when members of the Mansfield NAACP traveled to D.C. to take part in the March on Washington.

When Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke his epic words, there were Mansfielders there on the hill who heard his Dream and brought it back to our city.

In the Crowd:

And there were his neighbors—holding a small sign that said Mansfield Ohio NAACP.

For more background on Mansfield’s North End activism in the 20th century check out:

Hotel Lincoln and the Green Book in Mansfield: 1924-1961

Notes: